Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

The Neurobiology of Housing

It's fair to say that none of our states has a mental health program that's adequate to base a national system on. Some have areas that work relatively well but state administrations across the country are all looking at each other in hopes that a clear direction will emerge. Everybody's faced with growing numbers of mentally ill citizens at a time when the dollars available to care for them are shrinking.

One constant throughout the country has been a "top down" approach to the problems within our mental health systems. The top levels of organizations are always focused on political and economic factors. Administrators go to meetings with other administrators. Cost-shifting, business models, capitation rates, appeasing advocacy groups, and casting their bureaucracies in the best possible light dominate the agendas. The fact that none of those topics is sufficient to build a new mental health system on just doesn't come up.

Most people in the field will readily agree that it's the difficulty with providing good living environments that's the driving force behind our enormous social problem. But for all of our talk about the importance of basing our system planning on "evidence" there have been very few attempts to approach the housing issue in a way that will allow meaningful assessments and comparisons.

It's time to take a fresh look at the problem of providing good supportive housing for mentally ill people. We want to create a range of living environments that provide each patient with his best chance of recovering a good life and we want to do it in a way that makes the best use of each tax dollar that we spend. Any approach to system reform that isn't based on fixing our housing problem is almost certain to fail.

When a problem is this complex it only makes sense to use all of the resources that we have available. Our new understandings of mental illness, the existing findings of the Evidence Based Practice literature, and some older psychoanalytic ideas about therapeutic communities should all be contributors to a new mental health system.

Systematically determining exactly what we want to provide and how to do it in the most efficient manner possible will be necessary. We may even have to try using a little common sense somewhere in this process, as far-fetched as that idea might seem to jaded mental health professionals.

As reviewed earlier, the emerging models of mental illness are considerably different than those that were in place when we developed our current system of community care for the mentally ill. There is now a much greater awareness of the problems with neuronal migration and hook-up in the developing brain, and their ultimate role in causing mental illnesses. The longstanding, structural nature of many neuropsychological deficits has become more apparent. The idea that everyone would be able to leave the asylums and return to normal lives in the community because they now had access to new medicines seems pretty ridiculous in hindsight.

At the same time, the ability of the brain to change, at least to some extent, in response to environmental variables has also become better appreciated. What follows is a partial list of brain problems and adaptive capacities that should be taken into account as we try to develop the most humane and cost-effective programs to care for this growing segment of our population.

Altered Realities

Any housing or service programs that we develop must recognize that other people's realities may be very different from our own. We must also take note of the fact that mentally ill people will often have no awareness at all that their realities are different than those of others. The reality that our nervous system creates is the only one that we can experience.

The list of things that can go wrong with one's picture of reality is far too long to do justice to here. People may not be able to reliably distinguish between inorganic objects, things that are alive but not human, and human beings. Voices may comment on every action or thought. Enemies may be lurking everywhere. Grandiose convictions about one's special status or purpose can surface. Everyday occurrences may be imbued with weirdly individual meanings. But the overtly "crazy" symptoms that clients sometimes struggle with are just a tiny part of the brain problems that must be accounted for and dealt with.

Many people with severe mental illnesses suffer from anosognosia - a neurologically based inability to recognize that one is ill. But our current system of care is dependent upon the individual's ability to recognize that they are ill and seek help accordingly.

So our new housing and service programs for mentally ill people must deal with some basic facts. People may be psychotic but will be unable to tell that their mind is playing tricks on them. They may be unlikely to embrace our medications or treatments- some may even experience our effort to help as something that is inflicted upon them for problems that they don't really have. Many will be angry or demoralized because their lives haven't worked out in the ways that they expected and they won't know why. A tendency to blame others for their problems will be commonly encountered.

Many of these clients will have tremendous difficulties with empathy. They may be almost oblivious to the minds, feelings, and realities of other people. Social conventions may hold no meaning for them. Excessive clutter- sometimes reaching bizarre proportions- can develop when a nervous system attaches no emotions or motivation to the basics of housecleaning. Personal hygiene may be totally ignored by misfiring nervous systems. Difficulty adapting to change is predictable too.

If mentally ill people are going to stay in housing that we provide for them it will have to be because there's something in it for them to do so. It usually won't be because they believe that they have a mental illness and need treatment. They certainly won't stay in any place because they're concerned about the financial costs to the system when they move from apartment to hospital to group home to shelter and back again.

We need to create living environments that people will want to stay in. Places where they are truly treated with dignity and respect. Where both a sense of self-determination and a sense of belonging to a community are realistic possibilities. Residences that are safe, secure, ensure good meals, and provide necessary medical care. Places that we'd feel comfortable living in too.

Managing contact with other humans

The ability to titrate one's degree of contact with other humans is one of the simplest factors that should be considered when designing supportive housing but perhaps the most far-reaching in its implications.

Many mentally ill people are estranged from family and friends and have no sense of connection to anyone. Bringing in staff for a few hours of house-cleaning or shopping each week is helpful but does little to ease the feelings of anxiety and isolation that are so common in this population. Evenings and weekends are particularly difficult as few programs offer opportunities for social contact outside of normal working hours.

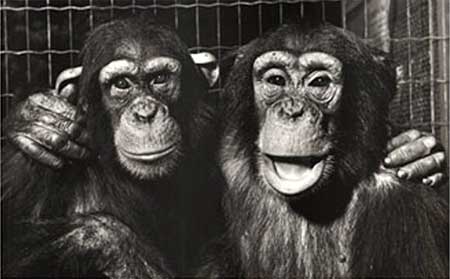

We humans are troop animals just like our primate relatives. We're hard- wired to be around other people. The absence of meaningful social contact and sense of community can be very hard on us. But having a mental illness can make obtaining those essential basic commodities seem impossible.

Those neurologic deficits in empathy and self-awareness leave many of our clients lacking in social skills. Social advances may be clumsy or obviously based on fulfilling the needs of the moment, such as asking for cigarettes or money. Attempts to reach out to people in neighboring apartments are often met with rebuff. Simply finding a place to be in the presence of other humans without being harassed, stigmatized, or exploited can be a major undertaking.

As is often the case with the mentally ill, housing problems often fall into a "feast or famine" situation. Either they're lonely, with few prospects for meaningful socialization or they're stuck in the presence of other humans, with little chance of escape.

In the majority of available housing environments if people aren't isolated in an apartment they're stuck in some sort of group home where they can't ever get away from other people. Small rooms with two or three roommates are very common. Opportunities for privacy are seldom available. It's no surprise that so many mentally ill people in nursing homes and other shared living facilities prefer to sleep much of their days away.

This difficulty in finding an acceptable level of human contact that is within one's control has important neurological effects. The importance of the hippocampus and associated structures in maintaining a decent mood and adequate cognitive functioning has become increasingly clear. We've learned that lonely people tend to sleep poorly and impaired sleep affects the ability of the hippocampus to generate new brain cells. Memory suffers. Depression, irritability, impulsive behaviors, and substance abuse become more likely.

Humans are always uniquely sensitive to the presence of other humans and this effect is magnified in the mentally ill. Whenever another human is present we must immediately find ways to classify and deal with the relationship. Competitive and sexual feelings are quick to surface. Experiences of anxiety, self-consciousness and fear are common. All of these emotional reactions can trigger the release of stress hormones. Those glucocorticoids can, in turn, directly impair the functioning of the hippocampus.

So too much or too little contact with other humans can be difficult for humans to tolerate. Not having a sense of being able to control the degree of interactions with others makes these stressors especially significant. And having a mental illness makes the issue tremendously more important. The brain structures that are affected are already abnormal so reserve capacity is much decreased.

A core component of any new housing programs for the mentally ill should involve providing an easy mechanism to control one's contact with other people. Small private rooms-even tiny ones- will usually be experienced as preferable to shared rooms. When designing group living spaces we should try to provide ways for people to be in the presence of others without being in each others faces, e.g. breaking up spaces for socialization into smaller, more private clusters.

Deficits in foresight, problem solving, and planning

Another enormous area of difficulty for our clients results from the way that their frontal lobes are hooked up and functioning. Many people with schizophrenia and other severe illnesses suffer a dramatic loss in problem solving abilities. Significant drops in IQ are very common with the onset of illness. These people may essentially lose the ability to use their "inner mental screens" to approach problems and imagine various possible outcomes. The ability to anticipate problems and actively plan for their solution may suffer. A sense of future is often lost as well.

These abilities may be present to some extent, at some times, but quickly fall by the wayside when the person is under stress. Clients often act impulsively when faced with a problem that their nervous system can't deal with. Or they may try to access help from caregivers by engaging in problem behaviors that require intervention and assistance.

A good residential system should provide ongoing help with day-to-day decision making, planning, and crisis management. The real art comes in developing trusting relationships with the client, allowing them to deal with whatever problems they're capable of handling, and not imposing an unnecessary degree of control.

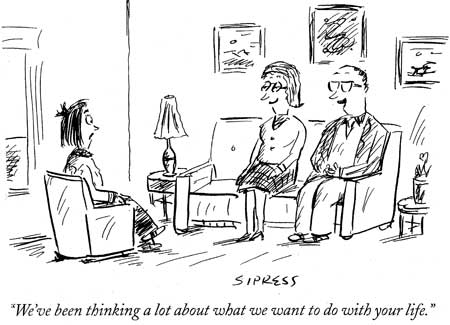

It really isn't a kindness to do things for people that they're capable of doing for themselves. But these issues are often very difficult for staff to conceptualize and deal with. We make errors in both directions, sometimes treating competent adults like children and at other times leaving overwhelmed people to fend for themselves when they have no chance of success.

New workers and those without training in the mental illnesses are particularly prone to problems in this area. Dependency, over-control, and oppositional behaviors can readily result when staff members assume more responsibility for the client's life than is necessary.

Mood Problems

Keeping one's mood within an acceptable range is a very basic but extremely important task of the nervous system. If the spirits get too high or too low it can be incapacitating for the individual.

Human mood problems can be "reactive" or "endogenous". Some people can respond to frustration, criticism, or their own negative thoughts with depressive symptoms that can escape normal control mechanisms. Perceived loss or even the threat of loss can trigger manic episodes. And sometimes, in those "endogenous" cases, mood disturbances seem to come over people without any discernable cause.

Regardless of how the mood problems arise they can be a real test for our residential programs. Depressed people can affect the mood of those around them. Suicidal impulses, gestures, and attempts all wreak havoc on the environment. Staff members may respond with over control born out of a heightened sense of responsibility for the clients actions.

Full-fledged mania is one of the most difficult syndromes for any residential facility or care system. Increased energy, talkativeness, grandiosity, and impulsivity can quickly become deal breakers that lead to eviction or hospitalization. So significant depression or mania can readily result in a transfer of the client to a new facility.

The real test of a living environment is its ability to contain the clients' extremes of emotions and behaviors. To find a way to soothe, to induce hope, and to provide firm limits when necessary. Support systems must find ways to deal with depression or mania without having to eject the client into some new, more expensive environment every time that moods swing too far in either direction.

Memory and cognition

The fact that we can remember anything at all, much less obscure trivia like the next lines of a song not heard for decades, is a stunning neurological achievement. How strange to consider that recollections exists as electrochemical potentials within our brains, to be discharged when the right combinations of environmental triggers and desire call for them. And we know memories can be quite fluid, reflecting the present reality as much as the one that's being remembered. Few areas of mental functioning are more prone to malfunction.

Many mental health professionals are unaware of the memory problems that our clients must deal with. Impairment of both visual and verbal memory are common in the schizophrenias and other severe mental illnesses. Depressed people may develop profound but reversible memory deficits. Clients with Borderline Personality disorder may exhibit dramatic quirks of recall, sometimes holding very different memories of an event depending upon the circumstances of the moment. People recovering from manic episodes can become profoundly confused, to the point where doctors may wonder if a dementia is involved.

Psychotropic medications often magnify these memory difficulties, particularly those that interfere with a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine that's essential to memory. We find that some clients do much better with one type of memory than another, for example recalling things that are written down more easily than things that are spoken aloud. This sort of information is sometimes available in existing neuropsychological testing but rarely seems to be utilized in patient care.

A good system of care will identify memory difficulties and other cognitive problems when they exist. A variety of strategies can be used to help the client deal with these deficits, including established schedules and routines, prompts, and giving information in the sensory modality that works best for the individual.

This is also an area where using technology will become increasingly important. In an ideal system of care all of our clients would have computer access and would receive routine information about medications, schedules, and activities via that route, in addition to others.

The importance of stimulation

We've learned that stimulating environments and novel experiences are very important for the very parts of the brain that so often are abnormal in the mentally ill. Unfortunately, our clients typically have tremendous difficulty building these things into their daily lives by themselves. Our existing housing programs often ignore these needs completely.

Many clients, whether they live in group homes or single apartments, have routines that are mind-numbing in their predictability. They never take vacations or travel to new places. They have little to excite or interest them. Nothing to look forward to or to set one day apart as special. For some, the only difference between weekdays and weekends may be a decreased chance of contact with professionals on Saturdays or Sundays. An altered sense of time is very common among the severely mentally ill. Many don't even know what day of the week it is.

It's no wonder that so many of our clients turn to drugs. At least it sets some time apart as being different. Even feeling lousy might be preferable to always having things be the same.

An optimal system would try to maximize the amount of interesting and new experiences that its clients were exposed to. Trips to museums, cultural events, movie nights, or just walks in new parts of town should be made easily accessible. Anything that enriches the living environment and increases the activity options available is likely to be cost-effective over time.

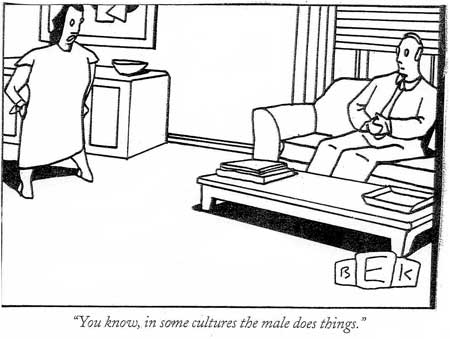

Meaning, control, and self-determination

The science of happiness is only recently beginning to receive some research attention. But most of us have at least some passing experience with the emotion. The things that go into the creation of a life that has at least occasional moments of satisfaction are pretty obvious when we step back to look.

We humans need to have a sense of meaning in our lives. It can arise in all sorts of ways but a belief that one has some control over how their life will turn out is an essential ingredient. When research studies create environments where the choices that an animal makes has no impact on the outcome of things, e.g. when a rat can just as easily receive an electric shock regardless of whether they move to the right or left side of the cage, a situation very similar to depression develops. The animals become listless and essentially give up.

Our current mental health system does a pretty good job of recreating that sort of situation for our clients. Consumers often feel that they're at the mercy of mental health professionals who make the actual decisions that will determine how their life will turn out. Major life choices such as where someone will live, when they can come and go, who they can associate with, and whether they'll have a job may be out of the person's direct control. Decisions about taking medications, attending day treatment programs, or having to go to an emergency room can be made by people that barely know the individual.

In our group living environments the choice of roommates is typically made without input from the people who are then forced to live together. Behaviors that will or will not be tolerated in the facility are also decided by workers rather than residents.

To make matters worse, when clients do take steps to improve their situation they may find that the environment actively discourages those sorts of efforts. Everyone in the mental health business has run into situations where someone works a little bit, ends up making ten dollars per month too much, and loses their health insurance or disability benefits as a result.

Enlightened supportive living facilities will find ways to maximize client choice and self-determination. Clients should have input into the rules that they must live under and the people that they must live with. Even small efforts to become more independent and functional should be rewarded - or at least not actively discouraged.

If we can truly shift to a position where everyone is responsible for their own life - where people are free to try new things and even make their own mistakes on occasion - we might finally begin to reduce some of the institutional dependency that has characterized our mental health system for decades.

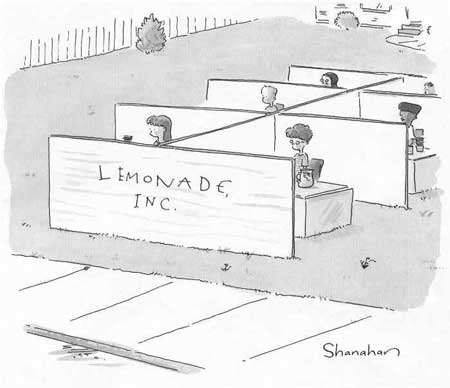

Work?

As much as we may complain about them, our jobs are tremendously important for most of us. They're an important part of our identity and self-esteem. Our work structures our time and provides an area for social relationships to develop.

Somewhere in the neighborhood of 85-90% of severely mentally ill clients are unemployed. Far too many patients have totally given up on the idea of ever working. We see people who declare themselves to be "retired" when they're in their thirties or have never worked to begin with. It's hard to find figures on how many clients that do work are in jobs that are unsatisfying, underpaid, or poorly suited to their nervous systems.

Our current vocational system depends on multiple agencies, both public and private, and all of them have their own administrative structures and overhead. We sometimes spend several hundred dollars per day to have a mentally ill client transported to sheltered workshops for mentally retarded people, just so they can make a couple bucks an hour for several hours of piecework.

While the "Evidence Based Practice" literature is clear in concluding that special supported work environments are needed for many clients to maintain employment our social programs have typically taken the position that mentally ill people should just work in competitive jobs like anyone else. The only alternative to the mainstream jobs that demand too much of them are those unsatisfying sheltered workshops. When it comes to work we set our clients up to fail and then complain when their failures cost us all so much money.

Future mental health systems will have to find new ways of providing meaningful employment for mentally ill people. We need a wide variety of jobs that can be tailored to the strengths and deficits of the individual. Determining exactly what those strengths and weaknesses are will be important too.

Providing incentives for people to truly succeed at work is another area that we'll have to do much better in. If we continue to set up a situation where someone can have a better quality of life with Social Security Disability Income, Medical Assistance, and a supported apartment than they can if they work in a part time, minimum wage job with no benefits- and then penalize people when they do try to work- we should brace ourselves for an onslaught of people who will never have any incentive to become more independent.

Engines require fuel

The importance of a healthy diet for good physical and mental functioning has become pretty well-accepted these days. And most would readily agree that hunger and starvation are at least a little stressful for people. But our systems of care often provide scant attention to the diets of our mentally ill people.

We've learned that having adequate amounts of omega III fatty acids help in creating nervous systems that are more resistant to depression and mania. Deficiencies in calcium, magnesium, zinc, and just about all of the vitamins have been linked to impaired mental functioning. It only makes sense that something as complex and high-powered as the human nervous system would be sensitive to all sorts of changes in the building blocks that make it up.

Like everything else, we run into problems on both ends. While some of our patients go to bed hungry or subsist by buying a frozen pizza every several days, others are putting on weight at alarming rates. The drug companies have been trumpeting their successes in creating new antipsychotic medications that don't cause the neurological side effects that our previous generation of drugs did. But they don't say much about all of the patients that are gaining weight - sometimes a hundred pounds or more- and developing diabetes or heart disease on these new meds.

An informed system of care would recognize that trying to "correct chemical imbalances" with layers of expensive medications doesn't make much sense if those brains don't have the basic chemicals that they need to function in the first place. We need to be finding ways to ensure that mentally ill people have access to healthy diets throughout our various housing and support programs.

Psychoeducation is crucial

Many, if not most, of our clients do not carry an understandable explanatory model of their mental illnesses. They've usually been told that they suffer from some kind of "chemical imbalance" but really have no idea what this means or what the implications are for their lives.

Clients are told repeatedly that good medication compliance is essential for them but they may not recognize any benefits when they do take the medicines. Sometimes they feel worse when they take their meds, battling fatigue, sedation, weight gain, and confusion in addition to all of their other problems.

Patients typically don't know who to blame for the loss of their dreams or what they can do to begin to recover a life that they can feel OK about. We psychiatrists should be providing solid information, in understandable language, about the nature of these illnesses but we often neglect this duty.

A sound psychoeducation program for clients and staff alike should be a backbone of our system of care. When we suggest that someone participate in an activity, use a particular problem-solving strategy, or be more compliant with their medications we should be able to articulate in a clear and simple manner why it is in their best interests to do these things. Developing a culture in which people's deficits are understood and recognized, while also appreciating their strengths and respecting their autonomy, will go a long way towards changing our system.

Transportation problems

Whenever groups of consumers are asked about problems in our system the issue of transportation is sure to come up. America is still a place where the vast majority of citizens get around by automobile. Our public transportation systems lag far behind those found in many other countries. But it's a very rare safety net client that has a car, let alone a valid license and insurance.

Getting around to appointments can be pretty good for those patients who qualify for our expensive medical transportation services but the types of programs that Medical Assistance will cover are shrinking. Establishing and maintaining eligibility for publicly funded transportation can be confusing. Making a few dollars can result in immediate disqualification. This is one of many areas where we actually provide incentives for people to achieve and maintain status as "disabled" rather than truly encouraging them to be more independent. We should make access to transportation a high priority whenever we design new housing programs or decide where to locate them.

There is undoubtedly room for some innovation in this area. Finding productive employment is a huge task for many of our clients and many of them do drive. Developing van or car pools, operated by stable clients, to take people to appointments, make scheduled loops through the city, or hook them up with bus lines would be an upgrade to our present system.

The value of exercise

Physical exercise has emerged as perhaps the single most important factor impacting on one's mental health that a person can control. Exercise provides benefits for the functioning of the hippocampus. It can have dramatic antidepressant effects, reduces anxiety, improves sleep, and can be a boost to self-esteem. Yet very few of our clients exercise regularly and our systems of care often disregard this need entirely.

Creating a culture where exercise is a regular and valued part of the living environment will not be easy. Providing ready access to exercise via groups, YMCA memberships, tai-chi, yoga or essentially any activity that results in an improved connection between mind and body will be useful, especially if accompanied by the sorts of psychoeducation and explanations mentioned above.

We're starting to find that exercises that involve the coordination of both sides of the body may have a positive impact on the functioning of the cerebellum, as it tries to balance out the various systems involved in creating our symbolic realities. Using drums, other musical instruments, and specialized exercises may help to boost the cerebellum.

Meditation, treatment of depression with phototherapy lights, "sensory integration therapy" and other non-medication based treatments are also being recognized for their very real effects on the nervous system. There is no reason to limit our therapies to those that can be written on a prescription pad.

Problems with impulse control

Controlling the impulsive behaviors that can arise in response to our environment and our emotions is one of the greatest challenges for a human nervous system. Our basic natures compel us to immediately act in ways that gratify our desires and relieve our fears. It is our capacities to delay action and to consider alternative ways of responding that set us apart from the other creatures. Not surprisingly, this is an area of significant difficulty for some of our clients.

Think of any human impulse and there will be people who have tremendous problems controlling it. Assaulting others. Stealing. Hoarding things. Screaming uncontrollably. Unwelcomed sexual behaviors. Running away from unseen enemies. Self-destructive acts. Uncontrolled substance abuse. The list is long and just about any behavior can result in loss of housing or hospitalization when taken to extremes.

The list of strategies for dealing with problem behaviors has to be a long one too. Therapeutic environments find ways to engage the reasoning, self-reflective parts of the brain to the fullest extent possible. Rewards for improved control, appropriate consequences for negative actions, and knowing when to just ignore people that are behaving badly are all necessary.

Responding to impulse control problems with the right combination of understanding, tolerance, and firm limits is one of the greatest challenges for any clinician or residential program. Creating an environment in which there is an ongoing expectation that people will treat each other well is vitally important but often ignored. The easy way out is to just ship the misbehaving individual off to some other place, where they become someone else's problem. But that strategy has not served our system or our clients well.

Negative Symptoms

Strangely enough, not doing things can be just as problematic for our clients as their difficulties with behavioral control.

"Negative symptoms" of schizophrenia represent enormous barriers to successful community adjustment for our clients that suffer from that disorder. Problems with will, motivation, a sense of future, experiencing pleasure, and forming decent relationships with other humans are extremely common among people with schizophrenia, as well as many others with different mental illnesses.

Compounding matters is the fact that negative symptoms generally don't respond robustly to medications. Oftentimes, medications actually exacerbate these problems via sedative side effects.

In most cases the genuine negative symptoms are a direct result of how the brain is wired in schizophrenia. Many patients with pronounced negative symptoms have evidence of malformed brains very early in the course of their illness. When the brain creates its picture of reality it may not attach the right emotions or motivations that will activate the person to do something.

While our present psychiatric system is, understandably, very concerned with reducing "positive symptoms" like delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking it's actually the negative symptoms that have the greater impact on the patient's long term prognosis and functioning.

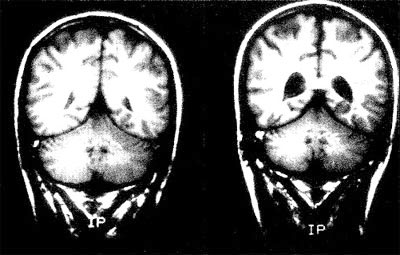

MRI scans of 28-year-old male identical twins showing the enlarged brain ventricles in the twin with schizophrenia (right) compared to his well brother (left).

We need to provide training to staff, family members, and clients alike about the nature of these negative symptoms and strategies to deal with them. Without such an approach these problems will continue to be mistaken for laziness, lack of effort, or character problems- with all of the dreadful consequences for individuals and families that are so common today. Developing environments that react positively to small successes but do not push the client to do more than they are ready for is another area that requires as much art as science.

Circadian rhythm disturbances

The consequences of having a brain that operates on a different timetable than other peoples' may not be obvious but they can be tremendously important for individuals and their living environments.

Deep-seated biological rhythms often go awry in the major mental illnesses. People with schizophrenia are often awake when other people are sleeping, then sleep until late afternoon. Well meaning mental health professionals then express dismay when the client doesn't show up for morning appointments or can't hold daytime jobs.

Depressed people often wake up during the early morning and can't get back to sleep. During manic episodes clients may go for weeks without getting more than a couple hours of sleep per day. Many people of Northern European heritage suffer from seasonal mood disorders in which their brain responds to decreasing day length with depressed mood, low energy, a craving for sweets, and a desire to hibernate until spring.

Sometimes it's possible to help people to gradually reset their biological clocks to more common patterns. Shifting bedtimes by no more than a half hour per week may be effective over time. Phototherapy lights that convince the brain that the day length isn't so short can be helpful during winter months. Research on Bipolar Disorder is now emphasizing the importance of establishing predictable rhythms of sleep and activity for the maintenance of a stable mood.

There are other occasions where the individual's propensity to live in his own time zone must just be respected and tolerated. This is a hard task in many psychiatric facilities. Long-term night staff have often come to believe that "the only good patient is a sleeping patient" and all sorts of conflicts get played out around who will decide when it's time to rest.

A good housing environment will offer help to people that have difficulty with sleep-wake cycles but will also find ways to allow individuals to follow their own rhythms without disturbing other people.

Brain Plasticity and its Implications

In the Emerging Model of Mental Illness we looked at the amazing flexibility that our brains demonstrate as they react to changes in the environment. The experiment with monkeys showed how dopamine systems can change in response to environmental variables. Having our own space to live is critically important. All sorts of stress reactions kick in when we are forced to share our living spaces with others, with important effects on how our brains are able to function.

An acceptable place in our social hierarchy is also crucial for mental health. A perceived lower place on the social ladder may predispose us to anxiety, irritability, and substance abuse.

The glucocorticoid hormones that mediate our stress reactions have been proven toxic to the very brain structures necessary for a good mood . Memory can also suffer in response to stress. Decent sleep can be very hard to come by when people are too isolated or too crowded together. Yet we often house mentally ill people in environments that any sane person would be anxious in. Any human is bound to feel nervous if he feels that he has little control over what will happen to him next. Adding layers of major tranquilizers, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers may calm people down enough to survive in these settings but we shouldn't be surprised when problems with day-to-day functioning result.

Research has shown the when people suffering from schizophrenia are exposed to harsh criticism the resulting tendencies towards decompensation can be as powerful as if they'd stopped their medications. The effects of social isolation or overcrowding on emotional functioning may prove to be even greater.

We're learning a lot about all of the negative things that can happen to humans when they're exposed to environmental factors that are too much for them to deal with. But we know almost nothing about the positive effects that may result from living in supportive environments that are designed to maximize enjoyment, stimulation, potential for growth, and a relative reduction in overall stress. We won't start to learn about those benefits until we can start providing those environments.

Do we really need to change?

The temptation is always to just keep doing what we've been doing. We can point to the wonderful successes that some mentally ill people have had with mainstream apartments when they were given the right sorts of supports. When things work well we should obviously continue them. No one should argue against anything that's provided a decent life for any of these people. But we can't neglect the fact that our current mental health system is a dismal failure for many of our most disabled citizens.

Jails, homeless shelters, and the streets are filled with mentally ill people that have not benefited from our system of care. And these very real social problems are getting worse rather than better.

For our seriously mentally ill people poverty, a lack of stable relationships, inadequate housing, inactivity, bad diets, and an absence of a true sense of community have resulted in stresses that they were never equipped to deal with. No human is equipped to function well when the basic elements so crucial to mental health are lacking.

We've tried to remedy this situation by adding expensive medications in increasingly greater dosages and combinations. But the findings from "Evidence Based Treatment" research consistently find that single medications in modest doses are effective for the majority of patients- at least when those patients are being housed in clean, decent hospital wards while the research is taking place. We can't assess the way that brains function without taking into account the environments that they're functioning in.

We should face up to the fact that as a nation we're just not going to provide each of our millions of severely mentally ill people with a decent apartment and thousands of dollars per month in medications and services. The social programs that have tried to accomplish this are already finding their budgets stretched beyond capacity and we're not serving anywhere close to half of our severely mentally ill people at that level.

Our current mental health system is overwhelmed by the sheer volume of clients who need basic housing, food, and supports. And there aren't going to be a lot of politicians arguing for the tax increases that would be necessary to support an expansion of services.

Administrators are already looking for any way out of these spiraling costs. We're facing drastic cutbacks in federal funding for mental health care right now. But it's also become clear that when these severely ill people aren't provided with the basic things that they need to thrive they bring even greater costs for society. Hospitals, shelters, and prisons are all extremely expensive to operate. And seeing so many homeless mentally ill people on our streets has to affect the mental health of the rest of us too. Our character as a people is never revealed more clearly than in how we treat the people that we see as different from us.

No one is advocating for a return to the old asylums, or for taking away apartments from people who prefer to live that way. What our society needs is a spectrum of supported housing alternatives for mentally ill people, from specially designed group residences to clusters of single units that are served by efficient and coordinated care teams.

Treating people where they live has all sorts of benefits, especially when hospital level services can be provided if they're needed. The individual doesn't have to keep reestablishing new relationships based on the frequent moves. A sense of community is fostered when people stick together through adversity. Clients can help each other instead of always being on the receiving end. Professionals come to understand people at a different level.

In an ideal system there should be no incentive to use symptoms as a way to get more or better services- the things that people need are already available in the living environment.

Developing new supportive living environments that meet the very real needs of our clients' nervous systems must be the cornerstone of any enlightened public mental health system. We have to develop programs that will serve large numbers of patients in the community in a humane and cost-effective manner. And we need to do it quickly.

In the sections on housing models we'll look at some common sense approaches to these social problems- solutions that would have been obvious back in the 1960's if we knew then what we know now. The term "paradigm shift" is turning into one of those catch phrases that become popular in large administrations but that is exactly what we need right now. And it's long overdue.