Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

Conclusions

Some of the major points of this work have been repeated so often that another summary may feel sadistic. But a review is traditional and some people do read books from back to front.

The most apparent conclusions are that:

- Our current mental health system is deeply flawed.

- The major mental illnesses reflect problems with the way the brain is structured during intrauterine life and early childhood.

- Correcting "chemical imbalances alone" will not lead to recovery.

- Mental functioning is enormously determined by the environments that brains develop and function in.

- The wisest thing we can invest in is the mental health of our children.

- It will be more cost-effective and humane to provide good living environments for people than to pick up the pieces with hospitals, prisons, and social programs when they've failed.

- We must be more thoughtful and realistic as we develop the mental health systems that will serve future generations.

There were a few basic assumptions that might have slipped by unnoticed.

A sculpture in four dimensions

The idea that we live in a reality of our own neurological creation is one that may be accepted on the surface but the total implications are hard to grasp. Consider a simple thought experiment:

Imagine that one hundred adults are given a knockout drug without their knowledge, whisked away during their sleep and, without a word of explanation, placed in identical environments. They wake up, alone, in large rooms that contain everything needed for their survival. Everyone has a variety of foods, the same small library of books, blank paper and pens, and an odd musical instrument that no one has experience with.

No contact with the outside world is possible. Electronic devices are not included. No mind-altering substances are available. The people have no way of knowing whether they'll be locked in their strange new environments for a day or for eternity. After a year passes we go in to see how they've fared. Think of the range of possible outcomes to this predicament.

For some people maximizing their personal pleasure and comfort will take precedence over all else. They'll quickly settle into a routine of eating, masturbating, and sleeping. They may pay no attention to cleanliness or personal hygiene. When the seal is broken both the people and their rooms are filthy. They've gained weight and are in terrible physical condition but otherwise are no worse for wear.

Others will become preoccupied with trying to figure out what happened to them. They may conclude that they've been exposed to the workings of a supernatural force. Figuring out the intentions of the God or devil that they imagine to be responsible for their situation may preoccupy them. Some may decide that they are actually in heaven or hell. They may feel that they're being punished for things that they've always felt guilty about.

Several people may become so depressed that they commit suicide. Others may just give up after a month or two and wither away.

There may be people who find relief in the absence of other humans and enjoy the solitude. Others will be driven mad by loneliness. At least a few will believe that other people are actually living with them. They'll be absolutely convinced that the voices they hear reflect the presence of other humans.

Surviving for as long as possible will be the primary goal for some subjects. They may see their situation as a test of their will and self-discipline and push themselves to rise to the occasion. They may emerge from sparkling clean rooms, fit, strong, and more self- confident then when they went in.

The prolonged quiet may lead to profound spiritual experiences for some. Others won't give matters of that nature a single thought.

In some cases a period of unprecedented creativity may result. There will be people who use their time to write autobiographies, journal their reactions to the situation, or produce poetry and fiction. The musical instrument may be the sole focus of attention for some. Others won't pick it up at all.

One hundred different people would produce one hundred different realities. Some would be mundane, others strange or deeply meaningful. When the survivors are asked to recall their year of confinement they'll have very dissimilar impressions. Many will even remember the identical physical environment differently.

So what factors determine the kind of reality that any individual will experience?

Beliefs and values will be extremely important. A person that decides that the most important thing is to survive as long as possible in hopes of being reunited with loved ones will have different experiences than they guy who believes he's been punished with eternal damnation. Someone who believes that no challenge is too great will have an outcome very much unlike that of people who are convinced of their own weakness.

As powerful as the meanings assigned to the experience are, their ultimate value is mediated by what they actually propel the individual to do. The behaviors that a person engages in during the year have enormous impact on the experimental results. What they decide to eat and how much. Whether they exercise. How much they sleep. How they spend their time. Reading, writing, and creative activity will produce different outcomes than lying on the couch.

As much as we like to define ourselves by what we believe, those beliefs are only electrochemical events within our skulls until they influence our behaviors. The reality that we experience depends on the interplay between the meaning that we assign to our world and they way that we live within it. If our lives are seen as profoundly unique works of art it's our actions that ultimately serve as the medium of expression.

How might we decide which of our subjects had the most successful experimental outcomes? Should our criteria be based solely on their survival? How much pleasure was experienced? Does the rationale that they adopted to explain their situation determine the value of their year? Does one religious explanation count for more than another? Are the creative accomplishments the ones we should view as most important? The physical condition that they maintained?

Some philosophers may immediately recognize that our little thought experiment captures the essence of the human condition. None of us know exactly why we're here or what life is all about. We all get a blank canvas and the chance to make whatever we will of it. Everyone's reality turns out differently. How should we decide which lives have value and which do not ?

A compulsion to comprehend the unknowable

Another core assumption running throughout this book is that the world that we live in is truly mysterious. The stuff that makes up our genes - DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid- is responsible for all living things. Look at any environmental niche on our planet, even miles below the polar icecaps where no sunlight has ever fallen, and DNA will have found a way to build creatures that can live there. But what drives the DNA? Where does it come from? Why does it exist?

The rapid change in human beings is another puzzle. Back in the 1970's there were only a couple of professional football players who weighed more than 300 pounds. Seven foot basketball players with speed and coordination were just as rare. Just a few decades later those sorts of physical specimens can be found on good high school teams. How can we understand this?

Classical, survival of the fittest genetics doesn't explain it. There have been too few generations and too little reproductive advantage to account for this dramatic increase in size and athleticism. Improved diets alone seems like quite a stretch. Steroids might account for a few of these specimens but certainly not most. Is it possible that DNA is even more adaptive and flexible that we ever imagined?

Another strange question is why the rate of expansion of our universe is accelerating. If we really started out with a big bang the stars out at the observable edges should be slowing down by now, like after any explosion. But that's not the case. They're speeding up.

The human brain itself is one of our greatest mysteries. "Three pounds of dog meat" as Kurt Vonnegut once termed it. 100 billion neurons, each alive and aware. The most elaborate reality projector imaginable. The source of everything that makes us different from other creatures and everything that we value about ourselves. But think about what it's ultimately made of.

The atom that we learned about in high school is composed of more than those protons, neutrons, and electrons. Over 60 subatomic particles have been identified already. Each of them exists in its own form for only a fraction of a second, and then turns into another type of particle. Energy is traded back and forth. No one can predict where any of these particles will be at any given moment. They can be pure energy or they can have mass. Time as we think of it doesn't exist for them.

Take the entire mass of all those particles, of every atom of every molecule of every neuron within our brains and you could fit the whole thing on the head of a pin. How weird to think that we're composed of dancing clouds of minute particles that ultimately create the worlds that we experience.

There have been all sorts of theories to explain our place in the universe.

We humans may conclude that DNA and all of the living beings that it's responsible for are the result of a week's work by a white male deity who looks suspiciously like someone's grandfather. We may think that all things resulted from the random actions of molecules colliding in a chemical soup over billions of years. Some believe that everything that exists is part of an interconnected whole that is far more complex than we humans can ever comprehend. The explanatory options are limitless.

There is always one thing, however, that we all agree on: That our beliefs on this issue are tremendously important. We're compelled to feel that our beliefs about reality must be the correct ones. Even more peculiar, at some level we react as though our beliefs actually decide the nature of the universe.

There is a powerful innate tendency to think that what we believe determines who we are. And perhaps that's true. Who's to say? But defining human beings based on what we believe about them exposes a quirk of our nervous systems - one that has very important consequences.

Was Abe Lincoln deluded?

Our nervous system is a binary one just like computers. Everything is broken down into a series of "either-or" choices. That fact carries all the way up through the core beliefs that we form about ourselves and the universe. If something isn't inside a circle it must be outside. If it didn't happen before it happened after. People die or they're immortal. Human lives have value or they don't. If someone isn't better than me he must be worse than me.

The brain has a very hard time with concepts like "all men are created equal". That requires a third possibility.

Object Relations theory suggests that the dynamics of human development make it even harder to have relationships in which each person has the same value. We're constantly interpreting our worlds based on those patterns of interaction that were laid down in core symbols during our childhoods. There was always a powerful adult in control of most of the commodities and a weaker child who had to depend on them for protection, feeding, and nurturance.

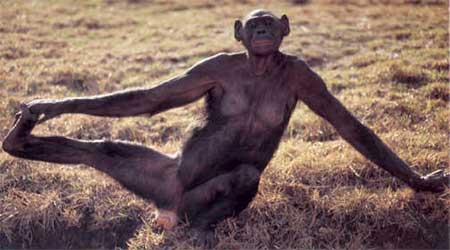

Our primate natures also ensure that we're always highly attuned to issues of social rank. Every baboon, monkey, chimp, or gorilla in their troops knows exactly where they stand relative to the others at all times. To think that these same mechanisms aren't operating in human nervous systems is to ignore our most basic nature.

We're simply wired to react to people as though they're of either superior or inferior status. We spend the rest of our lives asking that question about others in some form or another. Our brain might not even consider the possibility of someone being equal to us.

People will protest "not me - I believe that everyone is equal and I treat them accordingly". But when they take a brutally honest look at their lives there will always be instances where they react as though someone else is superior to them. It might be parents, entertainers, political leaders, or professional athletes but someone will be seen as more powerful or important.

Everyone has their favorite occupations, immigrant groups, races, and religions to look down upon too.

Here in Minnesota we're lucky enough to have the Wisconsonites. Primitive, foul smelling mouth breathers who drive slowly in the passing lane. Unfortunately, some people don't get the joke. The real humor in teasing our neighbors lies in the fact that we're essentially identical. Move the imaginary boundary between us a hundred miles in either direction and no one would notice the difference.

Our mistake is in believing that harboring feelings of superiority or a tendency to look down on others makes us bad people. In truth, we're all wired to see the world through those lenses. If we have to deal with these irrational feelings in one way or another it's best to have options. Getting them out in the light of day and poking fun at them is one of the best.

At some level we all know that we see the world in this hierarchical way. But no one likes to be confronted with evidence that they believe themselves to be better or worse than other people. So some pretty fast dancing can take place when we try to take an objective look at whether humans really should be regarded as being inherently equal. And especially whether we'll actually treat them as such.

Look what happens when we truly believe that some human lives are superior to others. We've created kings throughout our history. The basic idea is that these people are of noble lineage - that they're somehow qualitatively different from other humans. The whole "royal family" idea has reflected that innate drive to see others as more powerful or good or wise than us. Have the royals lived up to their billing?

It quickly becomes apparent that those "noblemen" are no different than other men. They're prone to the same human failings and weaknesses. They can be every bit as mean, selfish, stupid, or self-important as anyone else. And we counteract our tendency to put people on pedestals by poking fun at them or attacking them as soon as they're up there.

When we've taken the position that other humans are really inferior to us - less human than us - that hasn't worked out well or proven true either. Those kinds of attitudes have allowed humans to dominate, enslave, and kill other people throughout our history.

The "eugenics movement" is a chapter in America's history that doesn't show up in many of our textbooks. In the early decades of the last century there was a firm belief that people with mental illnesses were truly inferior to other humans. The next logical step was then to sterilize them so that they wouldn't contaminate the gene pool. That process was well underway, with the backing of some prominent psychiatrists, until the Second World War.

It lost favor when Adolph Hitler liked the idea so much he that brought it to Germany. With typical German efficiency he took our idea a step further. Why just sterilize the people with mental disorders so that they can't breed, especially if they cost a society money to have around? If they're really inferior why not just exterminate them?

He systematically murdered about 75,000 mentally ill people. It was only later that he turned his eye towards other groups of humans. Once the basic idea that some human lives are valuable and others aren't is accepted it gets easy to expand the list of the inferior.

We have to look harder for examples of what human culture is like when people really do regard each other as equals.

Some of our Native American tribes believed no man could tell another how to live his life. The idea that one person could tell another what to do was quite foreign to them.

The popular idea that chiefs were the commanders of the Indians is a white man's invention. In battle young braves often spoiled ambushes because their hunger for glory and recognition made them impatient. The older and wiser chiefs would shake their heads about how foolish and impetuous the young men had become. They'd try to reason with them or even shame them into behaving better. But they never questioned the idea that everyone was, ultimately, free to make their own choices.

Frans de Waal

The people of Nepal greet each other with "namaste" which, as every yoga student knows, means "I salute the God in you". Could there be some connection between the idea that a God exists in every man - not just some - and the absence of marauding bands of Buddhists?

One of the characteristics of groupings of people who share a common belief in the equality of man is that they tend to be pretty relaxed around each other. They laugh together and poke fun at people that puff themselves up to much. It's harder to be cruel to people who we perceive to be our equals.

We are often blinded to our core beliefs about where we rank compared to others. They're hidden beneath layers of either-or choices. And we're quite adept at convincing ourselves that we believe one thing when we actually harbor quite different assumptions. Looking at the ways in which we interact with other humans, especially those who are different than us, provides the clues necessary to discover where our heart is really at.

Throughout history our explanatory models of mental illness have been intimately connected to our beliefs about what it means to be human. There is no clearer indicator of our deepest assumptions about the value of human life than the way we treat people who suffer from severe mental illnesses.

To be, not to be, or what's in it for me?

Yet another root assumption is that from the level of our genes on up we humans are wired to be extremely selfish. Our safety. Our pleasure. Our status. These are the things that our nervous system concerns itself with at its most elemental levels.

Of course many will object to this crude view of human nature and point to the many instances where people behave in altruistic ways. But that seeming selflessness may break down upon scrutiny.

Imagine that you're in a crowded room and some religious extremist throws a hand grenade in through the window. Having only a moment to act you decide to throw yourself on the bomb - sacrificing your own life in a heroic act to save others. About as altruistic an act as one could perform and certainly worthy of the highest honor and respect.

But what motivated your decision?

Defining and supporting our beliefs about who we are can be among the most powerful driving forces for humans. We may even choose to die in order to maintain a view of ourselves which holds that we're noble or good.

This recognition of our self-centeredness is not in any way an attempt to be critical of our basic natures. It's just the reality that we must live with. And good psychiatry is nothing else if not an effort to help people deal with reality as it really exists.

A wonderful writer named Lewis Thomas once created a book called "Lives of a Cell". A central premise of the work was that even though we're self-centered by nature we humans can realize that it's in our own best interest to behave unselfishly. He called this "intellectual altruism". It makes perfect sense.

When we behave honorably, treat others with kindness, or transcend our own selfish desires of the moment it shows us what it can mean to be a human being. By rising above our basic natures and acting with the good of others in mind our own lives become better. We're opened up to the possibility of having friends and loving relationships. Of living in a society that allows us to be happier and more fulfilled than if everyone acts as though it's every man for himself.

Basing our plans on a realistic assessment of human nature

While living as though we aren't totally motivated by our selfish desires is within the reach of some humans, at some times, it's also clear that we can't routinely depend on this degree of wisdom from our fellow man. Any social system that's based on the idea that people will treat each other honorably or that we'll all follow the rules - even when no one is watching - is doomed to fail.

When we recognize that people make decisions according to what's in it for them we can use that knowledge to shape behaviors. This requires a sound awareness of the true incentives and consequences that we provide for our citizens.

If we really want people with severe mental illnesses to function more independently we'll have to create situations where it's in their best interests to do so. They'll require a lot of essentials but among them must be genuine opportunities for them to have a better life - whatever that may mean for them. Their own efforts to work or take better care of themselves must be translated into tangible rewards.

If people can have better lives by acting helplessly we'll be sure to create future generations of helpless and dependent people. Our current mental health system excels at this.

If we want to have more and better psychiatrists taking care of these people we'll have to provide incentives for them too. Financial incentives are not the only kind that work, even for shrinks. Providing jobs that are more intellectually stimulating, emotionally rewarding, or that are respected by our fellow men can be powerful motivators.

Having more symmetrical relationships with our patients and working with teams of professionals can make psychiatry a more attractive career option too. Expecting us to release our embrace of the medical model when there's nothing in it for us to do so runs counter to human nature.

If we're going to convince taxpayers that providing a meaningful safety net for our society's most disadvantaged citizens is worthwhile we'll have to be able to prove that their dollars will be used more wisely and efficiently than they are in the current system.

Themes of self-sufficiency, personal responsibility, and having our taxes pass through the fewest hands possible before reaching the needy cross party lines. None of us want a system that uses our hard earned dollars to sustain dense bureaucracies or further one politician's career over another's.

Could politicians be responsive to incentives too?

While this may seem incredibly pessimistic, it's really the politicians who will have to make the necessary changes in our mental health care. Like it or not, they're the ones who are ultimately in control of our public mental health systems. As much as bureaucrats may like to talk about grass roots decision making or "horizontal management" these administrations are always ruled from the top down and that's not going to change.

So we need to find ways to provide powerful incentives for our politicians to work towards a more humane and cost-effective safety net too.

When they're campaigning for office we should be pressing them to describe how they think things are working in our current social programs and where we need to make improvements. As clinicians it's our responsibility to put sensible options for system change before our political leaders. But we can't bring these ideas to fruition without their help. There are several actions that they can take immediately that would set us upon a better course.

A small percentage of all budgets currently spent on public mental health care should be devoted to creating model residential and community support programs. We should be looking for integrated and efficient ways to deliver the best quality of life possible for large numbers of people. Programs should be based on principles that make sense from clinical and moral perspectives. There should be contests aimed at coming up with the most promising approaches for caring for our mentally ill citizens and the best proposals should be funded.

If leaders are in favor of continuing to funnel our tax dollars into the pharmaceutical companies that lobby them we should hold them publicly accountable for that.

We should demand that our politicians work towards creating the most streamlined, efficient, humane mental health system possible. If they're not insisting that our densely complex web of bureaucracies be simplified we should be asking them why not. When they appoint heads of publicly funded mental health systems based on their political connections rather than a demonstrated interest in the clientele we should hold that against them during future elections.

That proposed requirement that everyone who receives public dollars to care for our disadvantaged citizens be required to spend some of their work week actually serving them might be the single most significant impetus for change that a legislator could promote. Without a grounding in the reality of the patients the bureaucrats will continue to make decisions based on their own interests. We should be putting ideas like this before our elected officials all the time.

We must let our political leaders know that even though severely mentally ill people aren't yet a powerful voting block these crucial societal issues are very important to the rest of us. When some brave politician embraces equitable models of universal health care or more sensible uses of public funds we should be flocking to the polls to applaud with our votes. One we get past our primate tendency to see ourselves as being of lower status than these leaders we can remember who is working for whom.

How long can we go on like this?

These are not academic or inconsequential issues that are at stake. The question of how many more mentally ill people our wasteful and inefficient system can support is becoming increasingly real and important.

In 1965 there were five workers for each Medicare beneficiary. If current trends continue by 2030 there will be only two workers for each recipient. Many of us in the mental health field can point to clients that have cost the system over a million dollars in services and treatment costs before their thirtieth birthday.

Locally we now have a county government using state dollars to hire a private corporation. That company's only job is to get as many people enrolled for federal Social Security benefits as possible. Where else but in modern day America would we have two branches of government hiring a private company to access dollars from another government agency?

Somewhere around half of those applicants receive approval for Social Security benefits the first time through and that typically takes about three to six months. Mountains of paperwork, medical reports, and eligibility determinations are necessary. The fifty per cent or so that are turned down for Social Security - and access to vital Medical Assistance programs- must go through lengthy appeals.

Many clients go through three or more appeals but most eventually are approved. They're denied access to health insurance and living subsidies during the appeal process but when the benefits are granted they're suddenly given a big check - often for $10,000 or considerably more. Clients that had no support at all one day are buying vehicles they can't afford or traveling to Las Vegas the next. And once people receive disability benefits around 90% of them remain disabled for the rest of their lives.

It's not just the needs of our present population of mentally ill people that we'll have to be meeting either. Anyone in the business will tell you that we're being flooded with unprecedented numbers of new clients and these people have more severe and complex combinations of problems than we were seeing even a couple decades ago.

As the numbers of people coming to us for subsidized living and health care continue to mount we'll only have a few options. We can raise taxes to pay for their care. We can turn some people away and serve others, devoting a lot of money to deciding who gets what and for how long. Or we can decide on the basic standard of life that everyone should have access to, then decide how to use our resources as efficiently as possible to provide it.

Regarding all humans as equal doesn't mean that everybody should get an equal piece of the pie. It means that everyone should have at least the bare minimum necessary to create a decent life for themselves.-What they ultimately do with their slice is up to them.

Another reason to change

While we've been emphasizing the arguments for cost effectiveness and fiscal responsibility in this work that's primarily because those are the ones that are likely to prove most persuasive to taxpayers and politicians.

The more powerful rationale for providing each of our citizens with the basics they need to have a chance at a satisfying life is one that we scientists have a little trouble with. It's hard to define and impossible to measure. But it has more impact on how human lives come out than any other commodity.

Love is not limited to humans. It would be hard to argue that those penguins who waddle day and night, 70 miles in each direction, to obtain food for their babies are not in some way driven by this force. Watching the adult penguins nuzzle each other when the females return leads to the same conclusion.

Some may argue that behaviors that are driven by the biological imperative to reproduce shouldn't count as love, as though that somehow cheapens them. But there is no denying that there are instances in the animal world where creatures act in loving, selfless ways towards each other even when reproduction is not involved.

How does this happen? If every living thing is a product of its DNA is love somehow contained in the double helix itself? Is there a genetic sequence for love? Could the power of love be somehow contained in the binding forces that hold the molecule together - or that bring it into existence in the first place? These questions, no matter how crucial to our attempt to understand ourselves, are better left for the poets.

There's no way to convince some humans that love does not exist between themselves and their pets. When love is present there is no denying it. Our hunger for love may even lead us to see it when it isn't there.

Love provides the other way in which we can transcend our selfish natures. It's the things that we love that determine what our lives will be like. No other factor is as important in a child's development as the love that its parents hold in their hearts. As we grow it's our passions - for music, sports, travel, work, hobbies, friends, cartoons, or whatever - that define us. Without the love of something outside of ourselves we feel empty and disconnected. The more love we have in our lives the happier and more fulfilled we are.

Ideally, it should be the affection that we feel for our fellow man that would convince us to rebuild our public mental health systems. There's just one small problem with that lofty goal though. Humans aren't always that loveable.

Why are we such irritating creatures?

It's odd that while we universally accept that our species is the finest creation to ever walk the earth there's no question that we humans can be extraordinarily painful to be around. The world is filled with little old ladies that are absolutely convinced that the company of cats is much preferable to that of human beings.

We tend to deny how much we can hate the people around us. But hidden attitudes surface on freeways and other places where humans remain nameless and faceless. We routinely complain to ourselves about how self-involved the people around us are. They're vain and entitled. Everyone is just looking out for themselves. We act like we'll live forever, as though our days are limitless and cheap. We're obsessed with sex but hide this awareness from ourselves. The same holds true for our intense aggressive feelings.

When experiments looked at the willingness of people to inflict painful electrical shocks on others it came as no surprise that many were more than willing to deliver them. But those studies only used sham electricity and actors who pretended that they were being hurt. Imagine if someone could create a device that would allow us to anonymously inflict pain on the people that we find annoying. The sales would put those of televisions and mp3 players to shame. Mount a button like that on our dashboards and some of us would wear them out in a week.

In truth we humans are extremely competitive, self-centered, petty, status-seeking beings who still manage to see ourselves in exalted ways. We're obsessed with our self- importance. We expect that we'll be taken care of by something larger than ourselves. We have grand plans but rarely fulfill any of them. When things don't go the way we wish our first tendency is to find someone to blame. At times we're so obnoxious that others can barely stand to be around us. And these are the healthy people.

How strange that the qualities that we despise in human adults were found in each and every one of us during infancy. That's the way we all come into the world and, peculiarly, that's when we're regarded as the most adorable. Only a few people manage to completely rise above their infantile world view and become truly responsible for their own lives. Pulling that off requires a combination of nature and nurture that many of us are not provided.

The beauty of biology

Job offers rarely pour in upon completion of one's training as a biologist but there are other benefits. Studying the plants and animals that share our earth reveals the undeniable beauty of their structure. The DNA of each organism somehow manages to produce creatures whose structure and function are amazingly adapted to the environments that they inhabit. Each of these species is so interesting in its own right that scientists devote entire careers to studying them. Even the single-celled organisms are so stunningly complex that we can never fully understand them.

Imagine how our world would look to a biologist from another galaxy. As fascinating as the other beasts are, there would be nothing to compare to the humans. Our ability to manipulate symbols in our mind and use them to communicate sets us apart from everything else. Our capacities to observe ourselves and to reflect upon the meaning of our lives are unparalleled too. If these observers viewed the earth as a zoo they'd be lined up to witness the splendor of the human beings. The other exhibits would be unattended.

So how is it that some people conclude that every other life form on the planet is innately magnificent except for the humans? How can those spinsters really think cats are better? Shouldn't the lowest human life have at least as much value as the live of every other creature on the planet?

Of course it all comes down to expectations. We find humans annoying precisely because we expect so much more of ourselves. We imagine that people should always be kind, generous, and thoughtful - especially in their dealings with us. But as soon as we conclude that we really are divine beings some jerk reminds us of our connection to the chimpanzees.

Mental illnesses have a way of magnifying everything that's weak and selfish and grandiose within us. The part of all of us that's driven to see others as less human looks first to the mentally ill. They're a convenient target for us to project the unacceptable parts of ourselves onto. It's no wonder that in so many cultures these people occupy the lowest rung of the social ladder. Or that when we look towards changing a society they'd be the logical place to start.

A canary in a coal mine

Our deepest conflicts about the meaning of human life are always revealed in the ways we treat people with severe mental illnesses. It seems very important at this point in our history for us to decide what the future will hold for them. The fate of the rest of us is intimately tied to this issue.

We're at a crucial point in the development of our culture. Previous ways of living that had been relatively constant for hundreds of years changed dramatically in the final decades of the last millennium. Our new high tech, fast paced, interconnected world will, in turn, exist for the next hundreds - if not thousands - of years.

As we move into our future, maximizing the mental health of the next generations of humans should be a global priority. Identifying preventable causes of mental illnesses and providing optimal environments for our children to develop in are among the most important tasks that we can accomplish.

The alternative will demand that a shrinking group of functional people work to support an expanding population that are too anxious, depressed, entitled, or psychotic to care for themselves.

How we treat the adults in our society that do have severe mental illnesses will have enormous consequences for our species.

We can view them all as throwaway humans who are not worthy of our care. We can try to ignore the problems that they pose for our society. We can hope that they'll just go away. Or we can spend lots of money trying to determine who deserves help and who should get the sink or swim approach.

It's also possible for us to approach the problem of mental illness in our society in a thoughtful, efficient, and compassionate way. We can honestly examine the attitudes and policies that have resulted in our current problems and try to adjust them. Systematic efforts to define optimal living environments that provide the things people really need - including opportunities, incentives, consequences, work, stimulating activities, and relationships - can take place. We can proceed as though every person has value and should be afforded a chance at a decent life.

These two different ways of conceptualizing and dealing with mentally ill people will, over time, take our society in very different directions. The path we choose now will a have tremendous impact on the world that all of our people will inhabit in a hundred years. There are human lives at stake here. Millions of them. We should never lose sight of that fact.

A mental health system, or a society, that views these people as worthless is ultimately insane. If human lives are not regarded as precious, but all that any of us really has is our life, where does that leave us?

A hallmark of the disordered mind is the tendency to keep using the same approach to a problem even when it's obviously not working. Healthy minds can step back to make realistic assessments of their situation and use new strategies when the old ones prove inadequate.

It should be clear by now that our very costly patient has at least a couple of toes in the crazy bucket. Deciding whether our current system of mental health care is truly insane will depend on how we respond to the immense social problem that is now before us.