Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

Basic Principles for a New Mental Health System

How strange to consider that at a time when leaders of our two political parties can't come together on any other issue they agree that it's necessary to cut support for Medicaid and Medicare. The question isn't if there will be cuts but how large they'll be. Could it be that our health care for the poor and disabled has become too good?

Certainly part of the impetus for the funding reductions is the growing awareness that the expenses for our publicly subsidized health care system are out of control. But there may be another kind of logic at work here.

Politicians seem to believe that if they can just starve the system for a while it will become more streamlined and efficient. They've got it partially right. If we simply allow these federal programs to grow unimpeded there will never be any incentive for them to become more functional. However, that's not the same as saying that cutbacks will be sufficient to cause system change. It's very easy to confuse "necessary" and "sufficient".

The more likely outcome will be even more gaping holes in the safety net. More "disposable" mentally ill people living in shelters, prisons, and on the street. Greater inequalities between clients that receive lots of help and those that receive none. And more incentives for people to behave badly if they're to be among the shrinking group of people receiving decent care.

Our mental health system won't really become more efficient or humane unless we make specific changes in the way it's structured.

Building a new system on a thorough understanding of mental illnesses and how they interplay with the environments people live in will be necessary. In fact it's pretty silly to think of starting from any other point. But that won't be sufficient. We'll need a number of other basic building blocks if we're going to come up with a better product.

Later we'll look at the question of whether significant system change is even possible if that depends on using the existing system to bring it about. Perhaps the best that we can hope for right now is to develop small model programs that will allow fresh approaches to the problem of caring for large numbers of impoverished mentally ill people in our communities.

In such models we can ask ourselves what an ideal system of care would look like and try to come as close to producing it as possible, even if just on a tiny scale. Starting afresh will also allow us to design approaches that integrate housing and support services in an organized, comprehensive way - a virtual impossibility in our current system of care.

If these model programs work better than the supportive housing systems that we have now we can use the things that we've learned to gradually transform the larger system. Even if these innovative models fail we'll have learned something that we can use in working towards further improvements. And at least we'll have tried to make a dismal situation better. Just making the effort will bring some hope to the clients, families, and mental health professionals involved in all of this.

A basic assumption and how to test it

In modern America we spend billions of dollars researching and developing new medications but almost no money is devoted to determining the sorts of living environments that would allow mentally ill people to function at their best. The reasons for that are pretty obvious when one thinks about it. But it's clear that these expensive new medications - which are seldom more effective than their older counterparts - have not been an answer to the mounting problems that our people are facing.

The lack of affordable housing for severely mentally ill people and other disadvantaged citizens is the driving force behind many of our society's most costly social programs. Until something is done to address this problem it really doesn't matter how much money we pour into medications and complex organizational charts. No one really starts to recover from these illnesses until they have a decent, stable environment to live in.

The previous chapter stressed the importance of providing environments that give each mentally ill person's brain its best chance of functioning well. If it's really true that there is a strong correlation between how well one's brain is working and the environment that he lives in the relationship should be relatively easy to demonstrate.

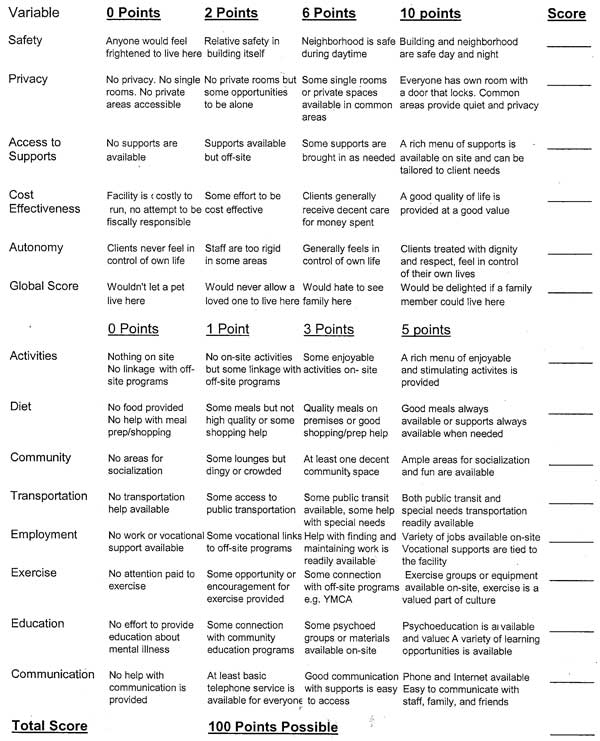

If we're going to systematically explore which sorts of living environments correlate with the best outcomes for mentally ill people we'll need a way to rate those environments along a number of variables. Then we can look at existing supportive housing programs to see which types do the best job of providing a good quality of life for their clients. It will also be possible to see which programs end up costing society the most in the long run.

We can even look at specific variables to see which ones are the most important in providing the kinds of outcomes that we want to achieve. If we ask the right questions we'll be able to accumulate the sorts of "evidence" that we really should be basing our practices on.

The same rating system could also be used to design housing programs that are as close to ideal as possible for the populations that they are intended to serve. The idea is to simply create supportive housing programs that deliver the highest score on the screening instrument at the lowest net cost possible.

This is a crude attempt to create a rating scale that looks at a facility's ability to provide some of the basic things that people need to have a chance at establishing a satisfying life for themselves. It could be used to rate any housing program, from scattered site apartments to heavily staffed institutional settings. The housing ratings would then be correlated with clinical outcomes.

It may be enlightening to see whether the programs that consume the greatest portions of our housing budgets are really doing a good job of delivering a realistic shot at recovery for these clients.

So what might a model housing program for severely mentally ill people look like if it aimed at providing the best quality of life for these people in the most cost effective manner possible? Obviously, there is not one answer to this question. We need a rich spectrum of housing alternatives to meet the needs of different client populations.

Examining a wide variety of options makes the most sense. Our mental health system should be creating all sorts of residential models. Options from simple prefabricated individual units all the way up to fully staffed, more "institutional" facilities capable of caring for people with a range of severe problems will all have their role.

Until there are places that fit the actual needs of these clients we can expect that they'll continue to bounce around between the places that don't fit those needs - at tremendous costs to everyone involved. The three models that will follow in the next section are just a starting point. It's the commitment to the process of developing the best models of community care that will be important.

Basic Principles for a Model Residential Program

When building something new it is important to create a strong foundation. We've seen how the basic assumptions about mental illness and community treatment that were present back in the 1960's have influenced the programs and facilities that we have today. Another house of cards is not needed. We should devote a great deal of attention to the basic principles that our model programs are built upon.

One simple way to approach this problem is to honestly ask ourselves what a real societal safety net should look like for anyone with a severe and persistent mental illness. What, if anything, should these people be provided with? What is the bare minimum that they should be able to count on having? Once we can agree on those questions we can then turn our attention to how to provide those basic commodities to everyone that needs them, in the most humane and cost-effective manner possible.

1) The whole person and the entire environment should be considered.

The deficits, strengths, talents, motivations, and desires of the individual client should all be important factors in any plan of community care. A wide range of environmental variables must also be part of the equation. Continuing to base our treatment decisions solely on the chemical imbalance that a psychiatrist imagines the client to have, while ignoring so many other important factors that can easily lead to failure, just doesn't make sense anymore.

2) Every client should have access to a single room with a door that locks.

A private space, the ability to titrate one's degree of contact with other people, and not having to worry about belongings being stolen are simple things that everyone needs. Having to live in rooms with other humans has enormously important effects on long-term brain functioning, creating unnecessary stresses for people that tolerate stress poorly. How many of us that don't suffer from mental illnesses have a steady series of roommates that are not of our own choosing? Most of us would find that way of living intolerable, especially if the roommates kept changing.

Even a tiny private room of one's own will usually be preferred to shared quarters. Obviously, if people choose to live together that's a different matter and the choice should be respected if possible.

We should determine the most basic unit of housing that we'll provide for our mentally ill citizens and at least that much should be available throughout our systems.

Absalon Hotel, Copenhagen Denmark

When it comes to creating small but comfortable living environments the Europeans are way ahead of America. This is a room of approximately 65 square feet. The door locks and bathroom facilities are down the hall. It would be an option that many people with severe mental illnesses would love to have. But it wouldn't cost that much in the long run to provide them with something a little larger and the quality of life benefits would be considerable.

Absalon Hotel: Free Upgrade

This is an upgraded room at the same hotel. It is about 100 square feet and includes a bathroom and small refrigerator. While small, it was quite comfortable. Buffet breakfasts were served each morning. Free Internet access was available in the lobby. A two block walk allowed access to a great public transportation system that covered every part of the country.

Anyone who wants to argue that our basic safety net for these clients should be larger or fancier than this won't find an argument here. But the idea is that something should be regarded as the bare minimum that our disabled people can count on having. If this is the best that we can do at least it's far better than the bottom line that we currently provide.

3) Housing should be long term.

Our clientele are often moved from place to place, usually as a result of changes in their clinical condition and often against their will. Living in several different places each year is very common. Moving is tremendously stressful for anyone. And these are people whose nervous systems are the most poorly equipped to handle stress or change.

Clients should be able to stay in places as long as they wish, providing their behavior doesn't become intolerable to those around them. If they eventually decide to move on to something more independent, we should support realistic efforts to do so.

Our current system is long on transitional living facilities but short on decent places to transition to. Ideally, these people would come to feel that the places they stay in are their homes. Just like the rest of us do.

4) The living environments that we provide should be safe.

People with severe mental illnesses carry their own demons with them and can feel unsafe anywhere. When we provide residences that are not secure or locate facilities in unsafe neighborhoods we only make things worse. Clients that are faced with situations that are realistically dangerous activate stress responses that then increase their propensity for irrational thinking.

In an ideal system irrational fears should stand in marked contrast to the safe and protected reality that clients actually live in.

5) Whenever possible, changes in a person's clinical condition should be met with changes in the types and levels of support that are brought to them.

Moving people to different places every time their symptoms increase or decrease is very expensive. Every time it happens there are costs for new assessments. Paperwork has to completed. Treatment plans are drawn up. Belongings have to be moved, stored or discarded. Funding has to be approved or reviewed. And all of this moving does not allow them to ever develop a sense that they are part of a community.

A single room at a large State Hospital

How much per month?

This is a room at a nice State Hospital in Minnesota. It is a small private room and adequate supports are available on site. But there are a few problems with this room. The biggest one is that it costs our system about 20,000 dollars per month for someone to stay in this room - and that is inexpensive as far as hospital beds go. The average person staying in a room like this gets somewhere around an hour of face to face time with a mental health professional each day, at most. Psychiatric visits occur anywhere from once per week to once per month and are typically brief medication checks. The psychiatrist that treats the person in this system is unlikely to ever see them again, unless the person is readmitted to the hospital.

Another common problem in our system is that people are reluctant to leave a room like this when crowded group homes, isolated apartments, or sleeping mats at shelters await them in the community. Patients are put in a position where they can stay in their nice room as long as they are behaving in negative ways that justify continued hospitalization.

In our current housing programs if there are 15 clients in a facility they may have 15 different psychiatrists and clinics to visit. Enormous efforts are sometimes made to insure that clients make it to their psychiatric appointments but no-show rates remain extremely high in this patient population.

Transportation can be inefficient and expensive. Many times professionals must pick clients up, bring them to their appointments, wait with them, and then transport them back home. Taking one client to a doctor's appointment can easily take up a half day of the worker's time. And when the patients do make it in to see their doctors the psychiatrist may barely remember them.

It makes a great deal more sense to bring psychiatric care to the facilities. The Doctors and other professionals get a different perspective on people's lives when they see them in their home environments. Longer term, more relaxed and symmetrical relationships can be developed. Transportation costs would be reduced. It wouldn't take that much effort to provide hospital level care when it becomes necessary simply by titrating the kinds and amounts of services that are brought in.

In the Assertive Community Treatment models a hidden benefit is that the services are provided by multidisciplinary teams of professionals that all know the clients. It's hard to say how much of the improvement in care that's been shown with ACT approaches is really due to that coordination and availability of services. Using similar teams to deliver services in residential facilities, nursing homes, or even assigning them to particular neighborhoods makes a lot of sense.

Connections can be developed with training programs at local universities, both as a way of providing direct service and to help trainees gain exposure to the treatment of people with severe mental illnesses. Even allowing students to live in the facilities during their training could be explored.

Obviously, people that want to receive their care from other providers should be able to do so. The idea is to offer on-site services of such quality and convenience that they will usually be a more attractive option.

If our psychiatric clinics are hard to negotiate imagine what it's like for these clients to deal with our economic assistance programs. Even professionals who have been in the system for decades are intimidated by all of the shifting rules and regulations that seem so impossible to keep up with. Eligibility for services can change overnight. If a form isn't returned on time people can lose their health care benefits entirely. Yet many of our clients move around so much that their mail can't catch up with them and others just don't open mail when they do get it. A simple system of eligibility determination and workers that come to see people where they live wouldn't be that hard to set up.

A basic departure from many existing models of care is the idea that staff would come to these model residences as visitors rather than as the people who are in charge.

This is an efficiency apartment at a new residential program in Minneapolis. It costs clients about 340 dollars per month to stay in a room like this. That extra $14,000 per month could pay for a lot of services to be brought in but that level of support is almost never required - or desired - by the clients.

6) Whenever there is work to be done in the facility we should let the clients themselves do it if they are interested and able.

We often overlook the very real strengths that many of our clients possess. Some severely ill people have college degrees or good work histories but those resources are rarely tapped. Work is important to just about everyone and a lot of the jobs that need doing in our mental health system can be done by the clients themselves. Even a small job that takes up only a couple of hours per week is still a contribution to the community and to the individual's self-esteem. We should obviously pay these people a fair wage for their efforts and this can come out of rent collected by the facility.

Our current vocational system depends on multiple agencies, both public and private, and all of them have their own administrative structures and overhead. Many clients now must earn a minimum of 65 dollars per month to avoid paying large "spend downs" for their Medical Assistance benefits but for some that goal may be impossibly difficult to meet. We sometimes spend several hundred dollars per day to have a mentally ill client transported to a sheltered workshop just so they can make a couple bucks an hour for several hours of piecework.

Nearly every immigrant group in our country seems to find a vocational niche for its members but so far we haven't found work settings that mentally ill people can reliably access. We should be looking for types of work that might match up well with the neuropsychological characteristics of our clientele. Horticulture, transportation, working as attendants in parking lots, moving and storage, and pet care are just a few possibilities. The availability of computers and training at the facility should open up other job options.

Anything that can be done to reduce the need for expensive outside labor in these residences will leave more money for the operation of the facility. Even providing comfort or supervision for other residents that need it may be possible for some clients. People will have better lives if they have a stake in the operation of the facility and are doing some meaningful work.

7) Input from clients, family members, consumer groups, and providers should be sought out as plans are developed.

This is just common sense and common courtesy. We'll develop better programs if we involve the people that are going to be served by them. If this sort of residence is built as a publicly funded facility we must be as open as possible about what we're trying to accomplish, what sort of problems we're encountering, and what is working well. Other programs should be able to learn as much as possible from these social experiments.

8) We can use existing service professionals in new ways.

Our current mental health system places clients into a complex maze that almost no one could negotiate without help. Locally, at least half of a case manager's time is spent simply trying to find and maintain housing for their clients. Helping to provide food, medications, transportation to appointments and interfacing with other agencies takes up the vast majority of their remaining time.

In the permanent housing models that will be proposed these needs are met much more efficiently. Moves would be dramatically less frequent. Food, medication, economic assistance, and psychiatric services would be brought to the site itself. This would allow for more efficient and responsive service delivery. A large component of the time of case managers and other support staff would now involve identifying changing clinical needs and coordinating the services that would be brought to the site to meet them.

An emphasis on understanding clients and the ways in which they interact with their environment, on using resources in creative ways, and not having to pass decisions through layers of distant bureaucrats would be a welcome change for many people in the field. Developing jobs that are more interesting and rewarding will help to draw more qualified and curious workers into the mental health professions.

9) In these models clients should be given as much freedom, autonomy, and personal responsibility as possible.

Anytime that clients are treated as people who have fewer rights than other citizens we should be able to explain to them exactly why that situation exists and what they need to do to have their rights fully restored.

In our existing group homes clients frequently lose all sorts of basic human rights. They are told where they'll live, who they'll live with, how much money they'll have, what they'll eat, what medicines they have to take, when they can see professionals, whether they'll be able to work, and what sorts of transportation they'll have access to.

There is no recognition of a right to have visitors in one's home. We often expect - even demand - that clients give up any hope of a satisfying sex life. When people do involve themselves in consensual sexual relationships they can quickly face eviction or even hospitalization.

Most of us would be a tad rebellious if we were subjected to this degree of external control.

There are a lot of reasons why clients refuse medications and other treatments but one of them is simply that these are among the few things left that they have any control over. When determinations are to be made about what behaviors will or will not be tolerated in a facility, or even whether someone can no longer live there, clients should have a strong voice in the process.

10) Court involvement in client's lives should be minimized and simplified.

Our current legal safeguards for mentally ill people are cumbersome and extremely expensive. Commitment hearings can take weeks to arrange and clients are kept in scarce hospital beds while awaiting their day in court. Each court hearing costs the system thousands of dollars but the requests for commitment or approval to medicate against the client's will are nearly always approved. Judges rarely have any viable options short of rubber stamping involuntary confinement and treatment requests because the clients are usually in dire need of these interventions by the time they come to the courts' attention.

These models will try to establish a mediation process to be used as a first step in resolving disputes about medication or treatment. Trained mediators will try to find some room for compromise around medications. Nowadays there is usually either blanket approval for psychiatrists to use as many antipsychotic medications and in whatever dosages they see fit or no order for involuntary treatment is given at all.

Clients can rarely get approval or assistance for trying to reduce their medications or even seeing what things are like without them. We often put them in a position where they feel that their only option short of a lifetime of medications they don't want is to stop them abruptly, even though it's becoming clear that this frequently leads to disaster.

Mediators may be able to encourage voluntary compliance with treatment. If the environment is one where client input and autonomy is valued there might be less need for drawing battle lines around medication compliance. In fact input from peers should be the first step in trying to persuade patients to comply with treatments if it becomes obvious that they're needed.

11) These models should increase clients' responsibilities as well as their rights.

Anyone who's had the task of running an inpatient psychiatric unit knows the importance of creating the expectation that people will behave themselves. If patients have to deal with realistic worries about being assaulted or having their belongings stolen it becomes very hard to relax enough to start getting better. The rights of individuals to refuse treatments must be balanced against the rights of everyone else to have an effective treatment environment.

If there are disputes about whether a person should be forced to take medications that they don't want we can use the mediation process. A videotaped interview with the client can take place, in which the pros and cons of taking or stopping medications - and the person's competency to make this decision - are reviewed.

In any cases where mediation around commitment or involuntary medication issues is not acceptable to either the client or the professionals making the request there should still be provisions for a regular court hearing. Hopefully, if the psychiatrist has a good ongoing relationship with all of the clients at the facility, as well as the mediator, much of the adversarial nature of our current legal processes can be avoided completely.

If a competent client decides to stop medications, knowing full well that professionals believe that this might lead to dangerous behaviors, then the client should be held responsible for the legal consequences of those behaviors. This is not really that different than someone firing a gun on a crowded street. People may not intend to harm anyone but they've taken a course of action that has put others at risk of harm. If bad outcomes do ensue from stopping medications there should be a videotaped record of the decision making process so that the court can review the client's competency at the time of the decision and the integrity of the process itself.

In most states the law is pretty clear about the sorts of situations that remove responsibility for one's own actions. Those situations are usually temporary and involve court proceedings. But in practice we frequently treat mentally ill people as though they aren't responsible for their own behaviors. While this may initially seem like a good deal, not allowing people to be judged according to what they actually do is not really a kindness. It perpetuates the belief that they are not as human as the rest of us.

The flip side is that when these clients aren't held responsible for their actions - like everyone else - there is going to be someone else that will be held responsible. And that fact contributes to the over-control and diminished rights that mental health professionals impose on patients throughout our systems.

Whenever someone is held liable for the actions of another the results are predictable. Having professionals making decisions based on liability concerns rather that clinical judgment is a natural result of our prevailing legal practices.

A basic belief here is that everyone should be held responsible for their own behavior - all of the time. To hold any other position requires us to draw lines about competency, intent, and responsibility that quickly become fuzzy when individual cases come up. It is the consequences that should change depending upon factors such as whether the person knew what he was doing at the time of an offence or if appropriate treatment was not available.

And it should be the person's competency when they make the decision to stop effective treatments - not their competency when they behave badly due to untreated illness - that should count when it becomes time to decide upon the consequences that they'll face.

12) We must have a range of consequences to offer in response to offences.

Arranging fitting consequences for negative behaviors is a challenge throughout our existing mental health system and errors are made in both directions. Sometimes competent patients are let off with no consequences at all just because they have a history of mental illness. Many times the jails and criminal justice systems simply don't want to deal with mentally ill offenders so they shuffle them off to the mental health system at the first opportunity - as though having to deal with our system were punishment enough.

In other situations people end up doing long stretches in jails or prisons for relatively minor offences committed in the throes of untreated psychosis. And the most common result of problem behaviors is the loss of one's housing. Many of us would be a little nervous if we knew we'd be evicted from our homes should we misbehave.

Our legal system becomes bogged down with issues that can't be resolved with facts. Trying to determine the inner mental state of a person is very difficult when the guy's right in front of you submitting to an examination. When we try to draw conclusions about whether someone knew what they were doing when they committed a crime last week it can be impossible.

The quality of one's legal representation and the finances devoted to buying expert psychiatric opinions have more impact on the success of a "not guilty by reason of insanity" plea than the actual mental state of the offender at the time of the crime. And how could this be otherwise? Is it really possible to create meaningful criteria that tell us who should be found responsible for their behaviors and who should be excused because of the severity of their illness?

Suppose someone suffering from schizophrenia believes that delivery trucks are following him around, observing his whereabouts and waiting for the right moment to deliver a package containing plastic explosives. When Aunt Tillie sends a Christmas fruitcake the client stabs the deliveryman with a large knife. Should the person be found not guilty because he truly believed that he was defending his own life from the lethal fruitcake?

What if one man in this situation only suspects that the package is a bomb - but he says that he's legally allowed to kill people because he is " God Junior ". Another guy is absolutely convinced that the package was meant to kill him but after the murder says that he knows that killing is wrong. Which one should be let free?

If the client has a type of schizophrenia that has proven unresponsive to medications should the legal outcome be different than if he responds well to drugs but refuses to take them? Does the ability of the person's treating psychiatrist to make a correct diagnosis and prescribe the most effective treatment enter into the equation? What about the role of substance abuse in destabilizing a chronic mental illness?

What if the recipient of the fruitcake has fetal alcohol syndrome rather than schizophrenia? Does a neurologically based inability to control one's basic impulses remove responsibility for one's behavior? Does the mother that drank during the pregnancy bear any responsibility for her offspring's misdeeds?

Imagine that there was a structural brain disorder that made it essentially impossible to experience a working conscience. No empathy for other people was possible, impulse control was severely compromised, and the likelihood of substance abuse was dramatically heightened. Some combination of bad genes or bad upbringing caused the disorder but it clearly wasn't the person's fault that they developed that kind of brain. What should we do with those people? (the brain problem is called antisocial personality disorder and most people in our prison system have it).

As our technology gets better these issues will only become fuzzier. More and more people will be able to point to tests that show they have a brain malfunction that they didn't choose. Deciding to hold everybody responsible for their own behavior, all the time, is the only approach that will make any practical or ethical sense.

Developing a wide range of consequences that can be tailored to fit individual situations will be necessary. Factors like the severity of one's illness, treatment response and availability, and the likelihood of further impulse control problems must all be considered when determining legal responses. Some clients that abuse or exploit others will have to go live with other people that behave like that. The sentence for other offences may involve mandatory medication compliance.

We can borrow and learn from the "Restorative Justice" movement when attempting to match consequences to misbehaviors. Small fines, community service, and confronting the person that was offended against should all be a part of our menu of responses when bad behaviors occur. Other clients and professionals can help offenders to become more aware of the effects of their behaviors on other people. Getting more options on the table besides the choice of incarceration or letting the person off completely only makes sense.

13) Psychiatric treatment should be informed and guided by a knowledge of "Evidence Based Treatment".

The beauty of Evidence Based Practice approach is not yet in the evidence itself. It's in the commitment to a process. In asking important questions and trying to answer them as well as possible. In valuing human lives enough to be clear about when treatment is experimental and what we're hoping to accomplish. And in acknowledging that we must honor specific obligations to people that subject themselves to our experiments.

We should make every effort to find medication regimens that are simple, rational, effective, and carry minimal side effect burdens. Whenever this information is already available we should use it - or be able to adequately explain why we're not. Generic drugs should be used when possible to keep costs down. Consumer choice and preference should be maximized.

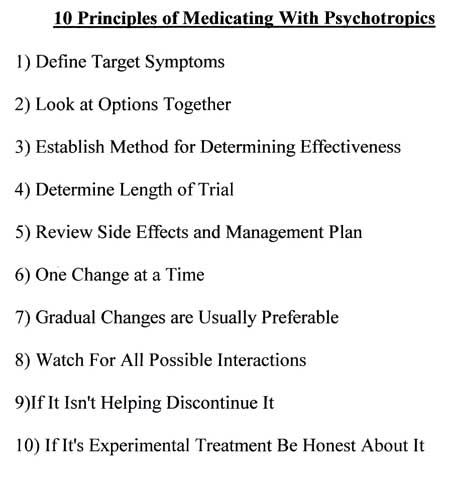

We need to be more sophisticated in our prescribing practices than simply using the medication decision trees that are now available. Values and common sense have to enter into the equation too. Here's a list of some basic principles for medicating people with mental illnesses:

A basic belief here is that providing secure, long term community living that meets the requirements of people's brains will reduce some of the need to calm people down with large doses and combinations of expensive major tranquilizers, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers. So will a careful, systematic approach in which Doctor and patient work together to find the simplest, most effective drug regimens possible. But as yet we have no evidence to support or refute these extremely important assumptions.

14) These basic housing models should be easily reproducible in a variety of settings.

Once we've developed some proven templates we can easily make modifications in them to accommodate the needs of special populations. Actively using MI / CD clients, people with involvement in the criminal justice system, patients with special medical care needs, the mentally ill elderly, and other specific groups can all be cared for by making modifications to these models.

More or less nursing and medical staff can be provided depending on client needs. Enhanced security may be necessary for some places, others may require nothing at all. There may be needs for groupings by gender or age. Clients that exploit or abuse other clients should have their own places to live in.

As our system develops we'll be able to provide an increasingly dense range of specifically designed environments. And, most importantly, we'll create sufficient capacity to ensure that nobody falls through the net unimpeded.

15) Assistance should be available for completing tasks that clients have difficulty with as a result of their illnesses.

Help with paying bills, finding employment outside of the facility, obtaining entitlements, and other routine tasks should be readily available. Clients should always be encouraged to do as much for themselves as they are able to.

16) Good nutrition should be a mainstay of these programs.

Programs may differ in terms of how meals are prepared and provided but there should always be a guarantee that healthy meals will be available to every client every day. Ongoing nutritionist input into the menus can be arranged. Where nutritional supplements are useful we should make them readily available.

17) Accessible transportation should be built into each program.

Facilities can be located near bus or light rail lines. Van pools to connect clients with public transportation or make loops through the city can be arranged. Clients that have automobiles and are willing to provide rides for others that need them should be fairly compensated for providing that service. A lack of affordable transportation should never be a deal breaker for clients trying to recover from mental illness.

18) These programs should be designed so that outcomes can be reliably assessed.

The costs of caring for these people should be measured and compared in real dollars, i.e. the total amount of money that taxpayers must pay to support the facility. It's natural for bureaucracies to consider only the costs that their agencies will be responsible for rather than net costs. Comparisons should be made between the total costs (housing, medications, hospital bills, case management, transportation, clinic visits, vocational programs, legal costs, etc) that each client incurs in the years prior to entering these model programs, and during the time that they live in the facilities.

We should compare these clients to groups of patients that receive services in other delivery models. Consumer satisfaction and quality of life should also be assessed. All of these financial and recovery outcomes should be made available to the public so that taxpayers can decide for themselves whether we're doing a better job of caring for people at a lower net cost to society.

A basic assumption is that it will be possible to provide a much more dignified and humane standard of living for these people at a small fraction of the costs for existing programs.

19) A guiding principle is that putting our scarce mental health dollars into facilities that are specifically designed to meet the needs of mentally ill people will prove to be a superb investment over time.

Fifty years from now there will still be people living in residences that we create today. If we create places to live that are as close to self-sustaining as possible we'll have more money available to serve other people. In the large bureaucracies that run our mental health systems there is an ongoing aversion to putting money into "bricks and mortar" but that basic assumption should be seriously reconsidered. Building a sturdy infrastructure of decent housing options is the wisest way to invest our mental health dollars.

20) We shouldn't only compare proposed housing programs to fully staffed halfway houses or hospitals.

There is always a tendency to automatically assume that residential programs should have round the clock staff available just in case something bad happens. It's hard to get past a focus on what is not available. It makes more sense to make our comparisons to the individual, scattered site apartments that are typically held up as the goal that our clients should strive for.

21) Medications should be provided in the most cost-effective way possible.

Medications provide the backbone of our current psychiatric treatments and that situation is unlikely to change soon. So it only makes sense to obtain and distribute these drugs in the cheapest way that works. There are four ways to get the medications and they vary widely in expense.

At the high end we can simply pay whatever the drug companies think that they can get away with charging for their brand name drugs. That's our current system. That's why we give almost twenty percent of our health care dollar to pharmaceutical company stockholders.

A somewhat less expensive option is to buy the brand name American drugs from other countries. Getting them from shipped in from Canada costs less than buying them here. Anyone who's traveled in Mexico knows that the same drugs cost less there too. There just seems to be something about being in America that makes medications expensive.

Providing generic drugs will become an increasingly attractive option. Many of our commonly used psychiatric meds are either off patent now or due to come off soon. There is little, if any, difference in effectiveness between brand name and generic drugs when they're run against each other in studies where neither the doctor or patient knows who's getting which. But even generic drugs have a very hefty profit margin built in to them. They only seem cheap because we compare them to the brand name versions that get all of the advertising.

The cheapest and most reasonable option would be to have the same government that has to pay for these drugs actually manufacture them. We could easily treat many of our clients for pennies per day without any loss of efficacy if we went about it right. Imagine the savings if we could knock 15 % or so off the top of our health care bill. As with other proposals, we could start small and make sure that outcome measures are carefully put into place before we begin.

22) We should develop our new clinical care models first, then determine the most streamlined bureaucratic support system possible.

Of course things currently work in reverse order but it wasn't always that way.

When the State Hospitals began the treatments were simple. Fresh air, a peaceful environment, work, and some human kindness were about all that we had to offer. The job of administrators was to make sure that there were enough sheets, towels, heat, and nursing staff to care for the patients. Over time this little organization took on a life of its own.

The basic principle in our present day is that a bureaucracy must somehow determine and control that fundamental interaction between clinician and client. Administrators go to meeting after meeting with other administrators. Elaborate policy statements are drawn up and then endlessly revised. Finally the pronouncements about the imagined improvements in clinical care are handed down.

The clinicians rarely take the time to read the latest administrative dictums. We just muddle on the way we usually do. Hearing what non-clinicians think clinical care should look like is regarded as an unfortunate nuisance that must be endured. Until someone has taken the time to learn about the mental illnesses and shown a willingness to be around the people that suffer from them their opinions are unlikely to carry much weight with the helping professionals.

The clients themselves are usually unaware of the very existence of those bureaucracies. Their experience with the mental health system is largely determined by things like whether their workers are kind to them or their disability benefits are endangered. The quality of their living space and the food that they eat are priorities too. When they do learn that the people in control of the mental health system are up to something their reaction is typically one of fearfulness.

Devoting so much of our recourses to administrative functions that really add nothing to the quality of life of the clients will become increasingly difficult to support as the human demands on our system continue to increase.

Developing clinical care models based on a sound understanding of mental illness is the first step. Once we have them in place we must turn to figuring out the minimum amount of bureaucracy needed to ensure that the clinicians have what they need to do their job and to make sure that the clients are getting the best care possible for every dollar spent.

23) People should have incentives to function more independently.

This is exactly what is missing throughout our existing mental health system, no matter how much we might try to deny that fact. There are only something like two housing markets in the United States where a person can rent a "market rate" apartment on a Social Security Disability income. Everywhere else one needs a subsidy of some sort to obtain even substandard housing with those funds. The way to get a subsidy, of course, is to demonstrate how much support one really needs. We insist that people become hospitalized or at least show that they can't care for themselves as a condition of receiving help.

Efforts to become more independent can quickly result in the loss of whatever assistance one was previously receiving. We sometimes see situations where a ten dollar per month increase in income can cost the clients hundreds of dollars in supports or subsidies. Obviously, this runs counter to common sense and does not promote moves towards self-sufficiency.

If access to a range of supportive housing environments was widely available a lot of the problems that people now have to demonstrate in order to get services would decrease. Clients would be free to take chances aimed at increasing their possibility of recovery if they knew that their housing wouldn't be jeopardized by success. There would be an enormous sigh of relief heard throughout our country if decent, affordable housing was provided for everyone that needed it.

Another way of looking at supportive housing

It's always difficult to get perspective on a problem when one is right in the thick of things. Traveling to new places to see how other people approach similar predicaments can be enlightening.

A recent fact finding trip to examine residential programs for mentally ill people in Denmark provided some interesting results. The programs there were not only far superior to ours, they were so good that they would never have a chance of being funded in America.

New construction in Odense, Denmark.

This facility for mentally ill young adults had four lovely buildings. Two of them contained five single apartments. Another provided a full spectrum of activities for these young clients.

Everything from recording studios to computer labs to ceramics workshops was on-site and it was all of high quality.

The fourth building in the complex was totally devoted to administration. It turns out that multifaceted organizational hierarchies were not an American invention after all. In fact some countries put us to shame in this department and Denmark is clearly one of them. This amazing residential program served a total of ten clients that lived in the nice little apartments. And those for those ten clients there was a staff of forty.

Activity area in Hillerod's Orion program

The same themes were encountered throughout Denmark's residential programs. Sparkling new facilities designed especially for mentally ill people, a deep-seated respect for the rights of the individual, very high staff to client ratios, and integration of the facilities into their neighborhoods were all commonplace. A social system aimed at providing each citizen with a chance for a good quality of life is an amazing thing to encounter.

The relaxed, friendly - even affectionate - relationships between clients and staff members were another eye opener. One small interaction captured some of the differences betweens the way the Danes looked at their mentally ill people and the current American view.

Apartments in an Aarhus program

A female staff member was showing a visitor around a housing complex in Aarhus when the tour was interrupted by a middle-aged man who suffered from schizophrenia. He wanted some money from his account "to buy cigarettes" and her suggestions that he wait until she was free weren't well received. He pestered her until she finally excused herself and got a few kroner for him to go to the local store. A short while later we saw him returning with a paper bag in hand. As he passed the unmistakable tinkling sound of bottle bumping against bottle was heard. The staff person chuckled and remarked that "those were the loudest cigarettes she'd ever heard".

When she was asked about her response to the fact that her client was obviously going out to buy beer she shrugged and explained that trying to talk him out of this practice hadn't yet done any good. She seemed genuinely puzzled to hear about how differently an interaction like this might have played out in America, with chart notes entered, stern lectures, possible referrals for involuntary chemical dependency treatment, and even the risk that her client could lose his housing. The idea that she would be telling another person how to live in his own home was really quite foreign to her. She summed up the prevailing attitude nicely when she replied "but it's his life".

Of course a system of care like Denmark's would never fly here in America. About half of our voters already think that our social programs are too liberal. Anyone advocating for the increase in taxes that would be necessary to transform our system into one like those found in the Scandinavian countries would immediately be branded as a lunatic.

But the lodging that was utilized by a skinflint traveling psychiatrist provided some other ideas about how to house large numbers of people in a humane and economical fashion. Youth Hostels found throughout Europe have been around for many years. They are utilized by people of all ages and walks of life. Some basic principles of their construction and operation could be utilized, with some modifications, in our efforts to develop housing for mentally ill people.

These proposed models would provide both privacy and opportunities for socialization. A sense of community will be fostered and meaningful work will be available. Providing food and basic services can be done in very cost-effective ways. The need for expensive outside agencies will be minimized.

While the amount of time spent in the presence of mental health professionals may not be as extensive as in the fully-staffed residential care models it will likely be much greater than in the scattered site apartments. And if we truly pay attention to the basic principles outlined here, the relationships between staff and client would be considerably more satisfying than those typical of our current system of care.

We can certainly just continue on the path that we've been on since for decades. But devoting a tiny fraction of our immense mental health budgets to testing new ways of caring for our severely mentally ill citizens makes so much sense that it's hard to imagine where a serious argument against the process will come from.