Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

Why is it so hard to be around mentally ill people?

A title like this may immediately bring up several legitimate issues. The most obvious is "Could there possibly be a more politically incorrect and insensitive question?" People may also wonder "even if it's true that the mentally ill can be difficult to be around do we have to talk about it? Wouldn't it be better to just pretend that this issue doesn't exist?"

The argument that will be made here is that, indeed, severely mentally ill people can be quite difficult to spend time with. That there are many reasons for this that we may not be aware of. That this issue has profound implications for both our mental health care delivery systems and the lives of people with mental illness. And, finally, that being able to take an honest look at this problem may hold benefits for all concerned.

Can this really be true?

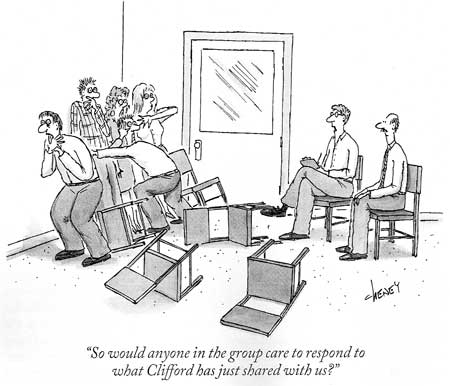

Newcomers to the mental health profession are often confronted with a peculiar paradox: If you follow our workers around it doesn't really look like we do very much. Just sitting around talking to other humans certainly doesn't seem that difficult. Yet these professionals will often complain that they're worn out, burnt out, or barely able to hang on until the weekend.

We anxiously await our next vacation and when we're away we look forward to our return to work with dread and resignation. Everyone who has been in the field a while knows people who have started their countdown to retirement many years - even decades - in advance of the actual event.

Perhaps unique to mental health is the fact that newly trained, inexperienced workers are often better able to help their clients than their older, more seasoned counterparts. It seems to be a fact of life that young people come to the field flush with optimism, energy, and hope only to gradually become cynical, jaded, and emotionally removed from their work as they spend more time with this clientele.

The mental health field is also qualitatively different from other medical disciplines in another important respect. In nearly every other field it is the best Doctors that care for the sickest patients. Even when professionals in these other areas move up their system's hierarchies into more administrative jobs they typically retain a fair amount of direct patient care in their work lives. Things are very different in mental health though.

In our business the care of the most severely ill patients typically falls to physicians and other professionals with the least amount of training and experience. For decades patients in some state hospital systems were cared for primarily by physicians who could not find other work. Many of these doctors were relegated to mental health because of problems with their licensing boards. Others had difficulty with the language. Many were never trained as psychiatrists at all.

One poor pathologist from a distant country had worked at a large state hospital near Minneapolis, trying to provide psychiatric care to some of our most difficult patients, for over a year before she came to her supervisor with the observation that "I think some of these people may not even be retarded". Her next comment to the supervisor was even more telling. "What does this 'fuck you' mean?" she asked.

While examples like this are extreme, there is no denying that in our field there is a real aversion to caring for severely mentally ill people. Psychiatry is a peculiar little corner of medicine and the care of the sickest patients is, in turn, a peculiar little corner of psychiatry.

In the mental health field much of the care of the sickest people falls on people who have little interest or training in providing it. And when doctors or other professionals are able to move into an administrative position it's extremely common to see them completely sever all ties with patients. In our field if you're regarded as really "high ranking" the proof is that you no longer have to take care of patients at all.

More important relationships are affected too

If more evidence is needed to demonstrate how hard it is to be in the presence of mentally ill people one need look no further than their interactions with friends and family. Even people that know and love the client will often try to see as little of them as possible. When visits do occur they are often offered with a sense of duty or obligation. It's very rare to see someone with a severe mental illness maintain long term friendships that were formed prior to the onset of their disorder. Even family members may sever ties with the clients completely over time.

This appraisal may seem a little too blunt and, of course, not every person with a mental illness ends up suffering such dramatic losses of social relationships. Indeed, some people with mental illnesses do manage to have fulfilling social lives. Many people suffer from mental illnesses but the people around them aren't even aware of the fact. But when the most severely impaired patients are the focus, there's little question that forming any sort of lasting or satisfying relationships can be extremely difficult. Everyone in our field has seen far too many patients who end up in near-total isolation, without any human contact save for the occasional visit from a paid professional.

The reasons for this inexorable loss of social relationships are complex. Many are rooted in the illnesses themselves. Severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia commonly lead to a loss of empathic abilities. Without the ability to monitor social interactions and factor in the ways that other people are responding to what you do and say communication can readily become a one way affair. No one likes to have their own thoughts and feelings disregarded.

These disorders can make humans extremely self-centered. For some psychotic people every single thing that they notice in the world, even the casual actions of complete strangers, is interpreted as having something to do with them. It makes sense that that attitude would often be even more prominent with family and friends. And few things are more distasteful to humans than seeing other people that are totally self-involved. We generally want to get away from people like that as quickly as possible unless there's something in it for us to stay.

That very self centeredness is often accompanied by a near-complete disregard for social conventions. People that work with patients suffering from chronic schizophrenia have usually encountered the "schizophrenic handshake". For some of these folks, if they shake hands at all it will be with whichever hand is closest to the person that's extending his. It's not like they put out their left hand to be difficult or funny. They just have lost awareness of - or don't attach importance to - how things are usually done.

Strange handshaking practices are seldom a problem. But when social conventions around bathing, dressing, conversation, or intruding upon the personal space of others are violated it leaves people feeling very uncomfortable. The desire to flee the presence of people that don't act like other people can be very powerful.

As is so often the case when it comes to our most impaired citizens, it can be extremely difficult to separate out the effects of mental illness and those arising from neediness. Most people that are ill enough to receive disability payments live far below the poverty line. They often have no way of obtaining even the most basic things that people need to survive. The cognitive problems arising from their illnesses may make it impossible to meet their needs through planning, strategizing, or consistently applying themselves to a task. So they commonly turn to the people that they know for help.

When family or friends are first approached by patients that are clearly in dire circumstances the natural inclination is to want to help if they are able. They may let the client crash on their couch for a few nights or give them a little money to help them get by until the next disability check. But it soon becomes clear that those sorts of assistance don't change much in the long run. In fact offering help may only increase the likelihood that the patient will be back looking for help again the next month.

When someone continues to present looking for assistance or companionship and doesn't seem to be working to make other arrangements it's natural to feel put upon. If that person doesn't appear sufficiently grateful - or even acknowledge the help - those feelings of resentment are even more likely to surface.

Family members often get to the point where they dread the calls from their mentally ill relatives or the staff members in whatever agency or hospital is trying to help them. The desire to distance themselves or finally say "enough is enough" may leave them feeling guilty. And nobody likes being around people that make them feel guilty either. Angry blaming, complaints about substance abuse, insistence that the client should be trying harder to find work, and arguments about taking medications often seem like inevitable outcomes within these families.

How to avoid being with mentally ill people

The professionals who are still "stuck" with seeing patients that other people want to avoid have usually evolved their own strategies to minimize the amount of time that they're with them.

The most prominent tactic is simply to spend as much time in meetings as possible. Talking with other mental health professionals about patient care is as close to having real patient contact - without actually being with a patient - as we can arrange. New observers to the field would likely be stunned to realize all of the time that we spend in meetings. Even busy clinicians may spend significant parts of their work week in meetings that do not include patients.

In our mental health systems there are many layers of employees that do nothing else but attend meetings or prepare for the next meeting that they'll attend. They become very involved with goals, business strategies, work plans, mission statements, and so on but many of these workers never do anything that truly touches the lives of people with mental illness at all. They seem to inhabit a peculiar "parallel reality" that is somehow connected to our mental health systems but never actually intersects with mentally ill people.

In a time of declining budgets expending so much of our scarce resources on a dense bureaucracy while patients live on the streets or in dismal poverty is increasingly hard to justify.

When the "I'm totally booked up with meetings" strategy of avoiding clients fails we still have our fall-backs. Increasingly, these now involve spending time in front of computer screens. If you've got a computer turned on, your eyes open, and a hand somewhere in the vicinity of a mouse or keyboard you must be working, right? Many mental health professionals now come to work and stay with their machine until it's time to go home.

Of course, this is another area where the efforts of the professional rarely result in anything tangible for the mentally ill people that are being served. One would dearly love to find out what percentage of time spent with computers is actually spent playing solitaire or looking at non-related websites. And now there's an increasing movement towards "telecommuting". Working on a computer in one's home reduces even further any chance of the professional having to be interrupted by messy patient concerns.

Why should it be difficult to be around these people?

When one starts to list the various factors that can make our work so emotionally draining the question can become "How does anyone manage to do this sort of work for any length of time?" Even more perplexing is the fact that many people who toil with seriously mentally ill people will tell you that they could never do any other type of work. Before turning to those questions, though, let's look at some of the very real factors that can make it so hard to be around the severely mentally ill.

First we must admit that we humans are, in the best of circumstances, a pretty nervous species. We have these big brains that allow us to attach emotions to realities that might happen, or to different possible interpretations of things that did happen. When we are able to comfortably interact with other humans it's often due to the fact that the other person somehow does or says things that allow us to relax a bit. We receive signals that tell us what sort of relationship we're involved in and what sorts of behaviors can be expected. But when dealing with mentally ill people the normal social conventions may not be followed. And sensing whether we are anxious and doing something to calm us may be beyond the capacities of their brains.

Another obvious but overlooked reason for our discomfort comes from the fact that we often feel responsible for the way these clients' lives are going, and especially for the ways in which they behave. Our professional reputations are closely linked to the way that our patients conduct themselves. Anyone who has had the experience of a client suicide or some other terrible outcome is all too aware how painful and real this responsibility can feel.

When things turn out badly we find it hard to escape the idea that there was something that we could have done differently or better that would have led to a different result. Once we've experienced that sort of pain trying to avoid further examples of it only makes sense.

Our administrative and legal systems often play into this idea that it is mental health professionals that are ultimately responsible for the behavior of their clients. Bad outcomes can result in a search for the worker who somehow did not do their job properly, with all sorts of painful consequences. Investigations by external agencies and threats of lawsuits are always a part of the potential realities that workers must deal with every day.

Of course this idea that mental health workers should somehow be able to control the behavior of people that they may see for, at most, an hour or two during a given week is pretty preposterous when you think about it. The patients themselves are some of the most unpredictable humans on the planet. They may live in a very different reality than the rest of us. The emotions and impulses that they experience may be out of proportion to things that are taking place around them. And they are some of the most difficult people to exert any degree of control over that any of us will ever encounter.

So our workers are left in an untenable position. Society may hold them responsible for the behaviors of people that they only dimly understand and certainly cannot control. Suicides and other dreadful outcomes are very common in the patients that they serve. There is an almost unquestioned basic assumption that the clients themselves are not responsible for their own behaviors. Somebody has to shoulder the blame when the inevitable bad things happen. Minimizing contact with the people that leave you in that sort of position can be a very attractive option, whether consciously chosen or not.

All of these very real phenomenon may be dismissed by some as the complaints of people that don't know what a real day's work is like. But there is clearly something powerful and important going on here, whether it's acknowledged or not.

A clash of expectations

Another basic reason for the malaise that we experience in the presence of our clients results from an underlying mismatch between what they want and what we're able to offer them.

The things that mentally ill people need and desire are really no different than the needs that all of us have. They want decent housing that they can afford, good food to eat, some meaningful activities, a sense of belonging, and realistic hope for a better future. All of these are, unfortunately, scarce commodities in our mental health systems. Instead we offer them the things that are suited to the needs of administrators, politicians, and other policy makers.

Despite their very common cognitive limitations and frequent loss of any sense of future, mentally ill people looking for help in our system are immediately confronted with an emphasis on things like "measurable goals", "treatment plans", and other abstract, paperwork-based commodities that have little impact on their actual quality of life.

There is never a shortage of suggestions about how to live their life differently - it's the things that they need to accomplish that that are in such short supply. If case managers and other professionals had an abundance of enriched living environments that provided work, food, and a modicum of supervision it would be much less painful to face their clients each day.

Decisions can be hard on the nerves

The process of making decisions presents difficulties for any humans. Examining options and choosing among them require both intact brain systems and a certain amount of self- confidence.

Mentally ill people may compound matters by attaching life or death emotional importance to the choices before them, essentially reacting as though one path must lead straight to hell and the other to eternal bliss. In fact, one could construct a rough spectrum of degrees of mental health based solely on people's approach to the decisions in their lives.

Paranoid people typically handle the uncertainty around decisions by becoming absolutely sure that one choice is the correct one. "Paranoid certainty" can be an amazing thing to behold. No amount of reason or proof will shake the convictions of a good paranoid once he's made up his mind about where the truth lies. As a very wise psychiatrist once said "Certainty is the realm of paranoids and fools - of that much I'm certain". Becoming sure that one is right can be an effective anxiety-reducing strategy, especially in the short run.

Somewhat healthier people may utilize the obsessive approach. A trick imposed by our nervous system involves convincing ourselves that an either-or situation is before us. We then must choose between two viable options and can drive ourselves crazy in the process. Humans can run through the list of possible reasons why option A might be preferable to B - and vice versa - for hours on end. The more we examine our choices the more complex and difficult the choosing becomes.

Truly healthy people are capable of what has been termed "lateral thinking". When confronted with a seeming either-or choice we can look for other alternatives that aren't so obvious. For example, when faced with any major life decision there is always the possibility of moving to Tahiti to work in a fish taco stand. Most of us don't consider that option.

We may also ask ourselves questions like "is it necessary to decide this right now?" " Is there more data that might allow me to make a better decision?" " What is the risk/benefit ratio of each available option?" And, most importantly, we can remind ourselves that any path that we choose can turn out to be a great one or a terrible one in the long run depending on the attitude we bring to our travel.

Since mentally ill people often have so much difficulty around decisions it often falls on the mental health professional to make them for the client. But this is very touchy territory. No matter how much the client lets us know, in one way or another, that they cannot or will not pull the trigger on a decision they may still resent us when we step in to help. And the emotions that they attach to the decision don't go away even if they can persuade us to decide for them. They simply share their anxiety or fearfulness with us by acting in ways that get us to feel these things too.

Or, as is often the case with people suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder they can set up situations where whichever option is chosen will be reacted to as if it were the wrong one. Eliminate decision making and the business of working with mentally ill people would become dramatically easier.

Another basic mismatch between expectations and reality involves the way clients react to the workers' efforts to be helpful. We mental health professionals may be a quirky and sensitive lot but we're not that different from other people. We have the same hopes of being appreciated and admired that anyone else does. But our clients may be quite different in their capacity to offer up anything like those high level emotional responses.

Envy and gratitude are two sides of the same coin. Which one lands face up depends a lot on the character of the individual. Our clients typically have nervous systems that are oriented in an even more self-centered way than those of other humans. Even when we're somehow able to provide clients with the things that they truly need and want their reaction may just be one of more entitlement. They may feel that we've only given them the things that they've always deserved so what's the big deal?

Patients may even harbor underlying feelings of resentment towards us. No one likes to be in a relationship where they are the needy one that must depend on the efforts of someone who is supposedly more healthy and functional.

While new workers may come to the field with expectations that patients and families will be eternally grateful for the help they provide, the reality that they must come to terms with is very different. "What have you done for me lately?", "Is that the best you can do?", and seeming obliviousness or indifference to our efforts are much more common than the tears of gratitude that we might have imagined would await us during our careers.

In fact long-term mental health professionals often become so jaded that when we do experience something that resembles appreciation we immediately become defensive and start to "look for the hook". Many of us visibly cringe upon hearing words like "you're the first person that has ever really understood me" or " I can tell that you really do care". We've simply learned that some clients will use the appearance of gratitude in a way to move us to provide more for them. The cynical view of human nature that can develop within ourselves is hard for many of us to come to terms with.

So we professionals must often deal with a lot of very real reactions to our efforts that would be hard for anyone to handle. Envy, entitlement, resentment, and manipulation are painful things for humans to have aimed at them. Feeling responsible for an unpredictable person's behavior, not being able to provide suffering people with the things they need, and watching people's lives turn out badly despite our best efforts carry their own emotional toll.

Any of these factors could throw us over the edge, causing us to hide in meetings, behind a computer screen, or in an administrative career. Strangely enough, however, the more powerful and important forces that can make being with mentally ill people so hard to be around typically take place outside of our conscious awareness.

"Primitive Defenses" and their effects

The underlying concepts about defense mechanisms were outlined in the "Implications of the Emerging Model of Mental Illness". The basic idea is that people who cannot deal with the anxieties inherent in being human can rid themselves of those feelings by distorting the reality in which they live. How "mentally healthy" a person is reflects the types of defense mechanisms that are habitually used and how much distortion is necessary to feel OK.

Devaluation and idealization are two primitive defenses that frequently come into play when dealing with the mentally ill. In these mechanisms the mentally ill person will see us as much better or worse than we really are, depending upon which version best suits their needs.

Clients may attribute all sorts of negative qualities to us. We may be seen as representatives of evil conspiracies, Nazis, demons, stooges in the service of big pharmaceutical companies, or whatever. Anyone who's been in the business a while has his tales of the goofy conclusions that people have reached about them.

It's always hard to be seen is such distorted ways. And having people attach powerful negative emotions like rage, terror, or genuine loathing to us can be particularly painful. But at least we can usually dismiss distortions like those to clear symptoms of a mental disorder.

Things get touchier when we're idealized. It's easier for clients to feel safe and secure if they believe that their care is in the hands of someone who is wiser, kinder, or more knowledgeable than other people. But distortions of this nature may be harder to write off as "symptoms"

The inflated images that our patients have of us are often not too far off from the underlying self-expectations that we hold of ourselves all the time. Eventually we all must come to terms with the fact that we are not nearly as caring or good as our clients would believe us to be. Or as we would want ourselves to be. This basic conflict between what we feel we should be and what we are is an enormous contributor to the pain of being human. Everyone must deal with it in his own way but the issue comes up a lot more often when one is dealing with people suffering from mental illnesses.

Complicating matters even further is the defense mechanism known as "splitting". This primitive defense is a favorite of people with Borderline Personality Disorder but, like all such defenses, is available for anyone to use at any time.

In splitting the other people in the world are divided neatly into two groups: Those that are idealized and those that are devalued. The "good people" and the "bad people". Which group a professional is assigned to is typically based on how much the client believes you like them.

The client also splits his or her self-representation - essentially becoming a different person depending on whether they're with the good humans or the bad ones. This can get very confusing for mental health professionals that work with the same client. One may interact with someone who is calm and rational while another worker may find the same client to be a raging maniac. Mental health workers are often pitted against each other, each concluding that the other is totally misunderstanding the client that they have in common. Anger, scorn, and a conviction that our work is superior to the other person's may readily result.

Then, to make matters worse, the client can instantly shift her opinion of any worker. A person who was previously "the only person who had ever cared" can be experienced as the embodiment of insensitivity just a moment later.

All of these distortions can wear on the mental health professional over time. No matter how secure we are, it's hard not to factor other people's perceptions of us into our own self image.

Some of us believe that whether a person is capable of becoming an outstanding mental health worker may be settled by about the age of five or six. Core beliefs about ourselves and resiliency in the face of onslaughts to our self-esteem appear to be determined early on. Training certainly helps but can't substitute for the sort of inner security that some workers just seem to naturally possess.

Projective identification and its nasty effects

Of all the many distorting forces that make being with mentally ill people challenging none is more important and pervasive than a poorly understood defense called "projective identification". This defense mechanism serves both as a way to protect the self and a means of communicating emotional realities that cannot be put into words. It may be the single greatest contributor to employee burn out in the mental health professions but many workers have never even heard the term.

Most staff members are familiar with the concept of projection. In that defense mechanism unacceptable parts of the self are "projected" out into the world and experienced as coming from outside.

The classic example is the paranoid person who handles his underlying feelings of rage and destructiveness by seeing them in the evil conspirators who are always lurking in the shadows. Sexual feelings are often ejected in the same manner. It's truly rare to find a paranoid person who does not believe that someone out there has some sort of homosexual designs on them - in fact that dynamic was at the heart of Freud's conceptualization of paranoia.

Projective Identification takes the projection defense an entire step farther but, by definition, the process remains outside of conscious awareness. Using the anger example, the idea is that first the angry feelings are "projected" onto the mental health worker. Then the patient acts in such a way to actually evoke those angry feelings in the worker. The patient not only manages to rid himself of the angry feelings that he cannot deal with - he gets someone else to feel them.

The dynamics of relationships in which projective identification is involved can become incredibly complex. The client not only rids himself of unacceptable emotions, he repeats patterns of relationships with others that were laid down in his brain before it became capable of making memories. All sorts of interactions are brought to life in ways that confirm the client's preexisting ideas about what the world, himself, and other humans are really like.

For a worker dealing with a number of severely ill clients coming to work can be like having a symphony played on one's emotional apparatus. The more sensitive and empathic the worker, the more intense the feelings that they must deal with. And few of those feelings are pleasant or easy to admit to oneself - if they were the client wouldn't be trying so hard to get rid of them in the first place.

If one were to survey professionals that deal with the severely mentally ill some common patterns of feelings would almost certainly become apparent: We often feel as though too much is expected of us. Other people don't seem to understand what we're going through. We may feel empty headed or fuzzy inside, as though incapable of logical thought. Angry feelings that we cannot understand may come up. Embarrassing sexual impulses may be activated. Feelings of internal badness or shame are all too common. People may feel picked on or unappreciated.

Even secure, respected professionals who have been in their positions for years will tell you that they somehow feel like someone is going to discipline or fire them at any time. And there is an extremely common tendency to react to other humans as though they were enemies.

When one deals with mental health professionals individually or as a group there always seems to be an external person or agency that assumes the role of "feared and powerful enemy". In fact, if there is a group of mental health workers that doesn't activate this dynamic they haven't been encountered yet. Someone, somewhere is assigned the role of the bad guy. Some person or group is seen as so malevolent or self-centered or greedy or incompetent that they can make life miserable for no reason at all. Typically that role is attached to administrators or supervisors.

In psychoanalytic supervision there is a great deal of attention paid to what has been termed "parallel process". The idea is that patients use projective identification to evoke their painful and unwanted feelings in the therapist. These feelings and communications are then re-experienced by the therapist in his interactions with his supervisor. Ideally, the supervisor has enough experience and self awareness to monitor the feelings that are activated in his relationship with his supervisee - to use those feelings as clues that can help to comprehend the patient's reality.

How the trainee is feeling in response to the patient and how those feelings are lived out with the supervisor become topics of endless examination and speculation. Eventually those musings lead to a deeper understanding of the patient's experience and are brought back into the therapy.

In the psychodynamic therapies it's taken as a given that all sorts of emotions will be brought up via projective identification and that the underlying distortions can sometimes be understood or corrected. The acceptance that emotions in the therapist may be powerful signals about the reality of the patient is one of the most valuable contributions of psychoanalysis.

Unfortunately, though, that sort of understanding is becoming rare as our field has become increasingly "biological". And when we don't understand powerful forces like these we can be influenced by them in all sorts of ways. Experiencing all of these painful emotions without some perspective on what's happening contributes to ongoing conflicts between patients, line staff, and administrators.

How does anyone manage to do this work?

When one considers all of the factors that converge to make working with mentally ill clients emotionally difficult it may seem remarkable that anyone stays in the profession for more than a few weeks. Throw in the fact that many of us come to the field with more than our share of quirks and insecurities to begin with and the task of remaining sane amidst so much madness may appear impossible. Yet many long-term workers in the field will tell you that they couldn't contemplate doing any other sort of work. Working in a "normal job" would just feel too boring and unimportant.

So what factors allow people to work with mentally ill clients for decades on end without succumbing to burn-out, disconnecting themselves from their work, or mentally turning their supervisors into some sort of inept monsters?

When one observes really good mental health professionals several common traits are often seen, regardless of the discipline that the person works in.

Some would say that a robust - even slightly "sick" sense of humor - may be the single most important factor that a mental health worker can possess. Laughter has all sorts of effects on the nervous system that can counteract the biological results of ongoing stress. A playful quality in one's work also helps us to keep some perspective on situations that might otherwise feel overwhelmingly hopeless. A certain amount of gallows humor can help to create a camaraderie among coworkers that makes coming to work every day possible.

Clients appreciate being able to laugh on occasion too. Who wants to have people constantly peering at them with an eye to determining what is wrong? And some of the things that mentally ill people do, say, or believe are just flat out funny. To feel guilty about seeing the humor in the work we do can be incapacitating.

Long-time staff workers have usually developed an ability to remember whose life it is that they're dealing with. Clients ultimately are seen as maintaining responsibility for their own lives and workers are responsible simply for doing their best to help within their own limitations. These workers don't take too much credit when things go well and when the inevitable bad outcomes occur they don't go overboard blaming themselves. If too much of the professional's self-esteem is tied to the client's progress that creates a lot of pressure for both parties.

A 2002 study out of the University of Texas School of Public Health found that working in boring jobs conveyed a 35% greater risk of dying over a ten year period than did working in jobs that were challenging. There appears to be something about novelty, decision making, and responsibility that are good for our brains.

While mental health professionals may offer a wide variety of complaints about the ways that they feel as a result of their work, feeling bored is rarely among them. When working with mentally ill people one never knows what the day will bring.

Everyone in the field has experienced those rare moments when they connect with someone in a way that they hadn't thought possible. Oftentimes these occur when the two people in the room are looking "outward" together at something that's happened in the world at large, rather than engaging in endless scrutiny of the patient and his problems. Taking pleasure in the occasional small successes and shared moments of understanding is what keeps many professionals coming back to work.

The best mental health workers never lose their sense of curiosity and wonderment. No other field provides us with so much information about what humans are really about. We are allowed to see the best and the worst of humanity - and everything in between. No matter how much we learn something new always crops up to challenge our existing ways of understanding things.

Humans are simply more complex than the human mind can ever adequately comprehend. And the effort to understand other people offers many insights into our ultimate struggle - to understand ourselves. Feeling lousy sometimes without knowing why is a small price to pay for all of the unique things that this type of work provides for each of us.

Seeing people with severe disorders actually recover a decent life for themselves, despite enormous challenges and obstacles, can be pretty rewarding too. Certainly this doesn't happen nearly often enough. And a knowledgeable professional would never be naïve enough to take credit for all of the things that must go into their client's recovery. But when recovery from severe mental illness does occur it can be truly inspiring.

Even knowing that we helped to alter the person's life trajectory by a tiny degree can be unbelievably gratifying and can bring a renewed sense of meaning to our own lives.

Implications for our mental health system

Mental health workers are placed into very complicated relationships where issues of status, control, and responsibility are wrestled with in unseen ways. It only makes sense to educate them about the dynamics of human interactions. Without some perspective on the feelings and impulses that arise the tendency to treat patients badly or run away from them entirely can be overwhelming.

There aren't a lot of health plans that are covering five time per week psychoanalysis these days. Not a lot of patients willing to spend years on the couch either. Everybody wants results to occur quickly. Treatment is guided by manuals and reimbursement formulas. Counseling is replacing psychotherapy. But neglecting the beauty and wisdom contained in decades of study about the dynamics of human relationships leaves workers unprotected.

Curiosity about our clients and ourselves engages parts of the brain involved with mood, stress tolerance, and impulse control. Our mental health field will attract quality trainees based on the degree to which the work is interesting, fun, and rewarding. Teaching and good clinical supervision will always be indispensable components of a good mental health system.

It's a very touchy subject but the other obvious conclusion is that, at an administrative level, something must be done to counter the powerful tendency to distance one's self from mentally ill people.

Who in their right mind would design a mental health system in which the main decisions are made by people that have no real knowledge of what it's like to be mentally ill these days ?

Requiring that administrators be well trained and experienced in the care of mentally ill people just won't happen. But it's not too much to ask that everyone spends some time working in direct contact with clients, just so they don't lose sight of what this is all supposed to be about.

It's reasonable for taxpayers to demand that each of us that work in publicly funded mental health systems spend at least a few hours per week in direct service to clients. If dishing up meals or driving people to appointments is the best we can do, we should at least do that.

If a referendum like this actually passed the collective wailing of bureaucrats would be audible in other solar systems. No one will ever admit that they have even a few free moments to spare. But until something concrete is done to bridge the enlarging gap between severely mentally ill patients and the people in charge of the system that cares for them we'll continue to base important decisions on inadequate information and an absence of direct feedback. And that's never a "Best Practice."