Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

How do people recover from mental illness?

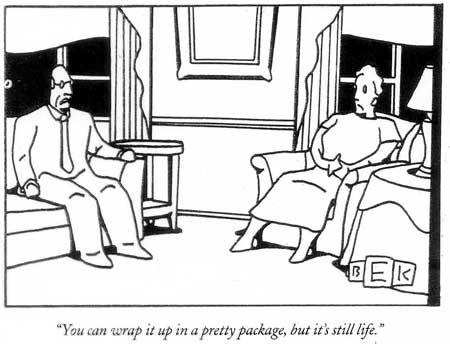

The concept of "recovery" has received a lot of attention in the mental health professions lately. As trendy topics go it's right up there with "Evidence Based Treatment," finding new people to label with "Bipolar Disorder", and shifting costs for the care of a State's mentally ill population to the Federal government. But, strangely enough, "recovery" is still a relatively new concept in our field and many of us had little or no exposure to it in our training. So it's no surprise that there would be a lot of confusion about what recovery from mental illness actually means.

A number of competing models of recovery are now available, each with its own set of basic assumptions and beliefs. So knowing which model someone is talking about is very important if common ground is to be achieved.

The "Broken Leg" model

This model is the gold standard against which all other models are measured. The idea is that the person recovers from mental illness in the same way that someone with a broken leg does. After the healing is completed the limb is supposed to be just like it was - perhaps even a little stronger - before the break. This analogy obviously has a great deal of appeal for mentally ill people and their families and it frequently shapes the expectations that they bring to treatment.

One occasionally does encounter people who have recovered in this way. There are examples out there of people who have clearly suffered from schizophrenia or other major disorders yet still manage to work in high level jobs, remaining symptom-free and never returning to psychiatric hospitals. Some of these folks work in the mental health field, educating professionals and consumers about what is possible in terms of recovery from major mental illnesses. There is no denying that this type of recovery exists. Whenever it's seen it represents an enormous human achievement.

The main problem with the 'broken leg model" is that it raises false expectations for many people, setting the bar at a height that very few will be able to achieve. And there's always that human tendency to believe that what works for us will work for everyone. The chemical dependency field is filled with people who think this way - whatever they did to become abstinent is what all of their clients should do.

The harsh reality when it comes to schizophrenia is that very few people can go on to have the sorts of lives and careers that they would have had they not suffered from the illness. The same idea holds true for many people suffering from severe forms of some of the other disorders. If family members look to those few amazing individuals who seem to completely recover from a severe mental illness in order to make comparisons with their loved one's progress they will usually be sorely disappointed. Angry blaming of the client or the professionals charged with helping them can readily occur.

The symptom control model

This is the model that's almost universally embraced by psychiatrists. In fact many of us never consider the possibility that other models exist. Of course our own ideas about recovery also rub off on the clients and other professionals that we work with so this has now become the prevailing recovery model throughout America's mental health systems.

In this model control of the symptoms of one's disorder is equated with "recovery". The model grew out as a natural consequence of the old "chemical imbalance theory" of mental illness. Symptoms are seen as the result of mysterious and ill-defined chemical imbalances. The psychiatrist's job is to prescribe medications aimed at correcting the imbalance so that the symptoms will go away. If the symptoms are well-controlled then we've done our job.

The rest of our army of mental health professionals is then given the task of trying to make sure that the patients continue to take those chemical imbalance correcting medicines - usually indefinitely and often against their will. When symptoms do recur it's assumed that either the patient has stopped taking his medications or that he now needs more of them. A flare up of symptoms is almost always met with a trip to the psychiatrist's office or to the psychiatric hospital so that adjustments can be made in the medications.

There is certainly nothing wrong with our focus on symptom control. Psychosis, mania, and depression can all be disabling and people usually function better when those sorts of symptoms are relieved. The problems come when people believe that the control of symptoms is supposed to naturally lead to recovery from the underlying illness.

When actual patients' lives are examined one finds, unfortunately, that there is a lot more to recovery than taking just medications to control symptoms. Millions of patients are given medications that result in a reduction of their symptoms but not that many go on to become more happy, productive, or functional. Many of these clients who have had their symptoms reduced via medications stop taking them at the first chance that they get. And having a sense of control over one's own life will usually be experienced as far more important than having symptoms reduced, especially given the fact that many mentally ill people never come to believe that they are experiencing symptoms of a mental illness in the first place.

Stages of symptom control

When one looks at large numbers of mentally ill people it seems that some general stages of development are often followed when it comes to symptom control.

At first the symptoms are uncontrolled. The client may not believe that their voices, strange new beliefs, or mood changes are in any way a symptom of an illness. Oftentimes they're not even aware that they've changed at all. They may try to hide their odd experiences from others for as long as possible. Family members may sense that something is different but attribute the changes to stress or substance abuse. So symptoms are present but are typically denied and no effort is made to reduce them through medications or other treatments.

In the next stage symptoms are recognized as resulting from an illness, at least by people around the mentally ill individual, but any symptom control takes place at someone else's insistence. Patients may be forcibly taken to the hospital or outpatient clinic after symptoms cause sufficient problems with functioning or behavioral dyscontrol. The patient may be medicated to reduce the presenting symptoms but some degree of coercion or reduction of their rights to make decisions is often necessary to persuade them to take their medications.

At this stage clients may "cheek" their medications or otherwise try to convince treaters that they're taking medications when they actually are not. A great many clients appear to remain at this stage of symptom control indefinitely, never willingly cooperating with any framework of belief that labels their experiences as "symptoms" or requires medication compliance to reduce them.

At the next level of symptom control the person begins to accept the idea that they have an illness that causes symptoms and begins to cooperate with the professionals' efforts to manage the symptoms with medications. We psychiatrists see this type of client as "gaining insight into their illness" and applaud their newfound willingness to participate in its management. These clients are regarded as the "good patients". If they seem to accept our medications with a bit too much passivity or respond to the psychiatrist as though we're supernatural beings that's not seen as a problem.

Clients often shift to a position where every uncomfortable feeling or impulse is now seen as a symptom of their illness and it's taken on faith that medication adjustments should follow any new complaint. Many clients stay at this level of functioning forever once they've achieved it and the psychiatrist may believe that they have actually "recovered" as long as symptoms are not prominent or identified as problems.

Sometimes clients do move on to a more adaptive level of symptom control. Here, the individual clearly recognizes that they do have to deal with symptoms of a mental illness but the ultimate responsibility for symptom management is owned by the client himself. The psychiatrist's role shifts to that of trusted consultant. Medications may be prescribed and a certain way of conceptualizing the illness may be offered but the client decides what does or doesn't fit in with his approach to managing his own life.

At this level there is often an emphasis on maximizing lifestyle factors such as sleep, work, nutrition, and a comfortable living environment to reduce stress and control symptoms. Simple medication regimens may be settled on but there is rarely the sort of complex polypharmacy that's often seen at the other levels and there is not the expectation that every new life problem should be met through medication adjustments.

Of course these clients may present problems for the psychiatrist. Our own ideas about what treatment relationships should look like obviously have a great deal of impact on our clients and how they see us. Most of us have been indoctrinated in a "medical model" in which the doctor makes decisions about treatment and it's the patient's job to simply comply. While "trusted consultant" is not a bad sort of relationship to have with someone it can be confusing if the Doctor is used to the model in which they remain in charge.

"The client costs the system less money" model of recovery

This is the recovery model that's favored by administrators, politicians, and policy makers. In it the goal of recovery is always to move the client towards utilizing less expensive services. If the person is in the hospital a lot the goal is to have them live in the community. If they're requiring a lot of services to get by in the community the goal is for them to function more independently. The ultimate goal that's held for everyone is to have them working in jobs that allow them to be self-sufficient. In this model it's the client who no longer costs the system any money that represents the ideal to which all others are compared.

The farther an administrator is removed from actual clients the easier it is to assume that everyone's mind works like his own. There is an almost inescapable tendency to believe that approaches that would work for the administrator will work for everyone. As a result our system is now pushing to have everyone working towards recovery in a linear - even obsessive - fashion. "Achievable goals" are to be set. Problems are broken down into small pieces. Progress is measured at each step of the way so that the administrators can know which programs and approaches are moving their clients along that path towards self-sufficiency. And any treatment approach that has not been subjected to the necessary research that allows it to achieve the status of "best practice" or "evidence based treatment" is looked upon with skepticism.

This sort of approach is completely understandable given the financial realities that system planners must deal with every day. Business models that emphasize cost-certainty and proven outcomes are awfully attractive when you're responsible for a system of care who's costs could spiral out of control at any moment. But when "recovery" becomes a commodity that is supposed to be regularly produced via proven formulas that doesn't quite square with the clinical realities involved.

Clients, by definition, are not always in a place that will respond to a heavily structured approach that's intended to make them less burdensome to the greater system. Many will flee at the first glimpse of a workbook that is to be used to break down their problems into those simplistic components. Others won't buy into any relationship in which the professional is supposed to determine what is best for the client. A lot of patients have been through countless changes that were billed as representing a new and improved model of care without ever seeing any tangible differences in their lives as a result.

When the actual goal of treatment is ultimately to make some professional look better in their own job some clients will smell that out and reject it right away. And it's becoming increasingly apparent that the things that many clients truly need to recover are not the sorts of things that they can get by sitting with a professional that has some new piece of paper in front of them.

The "get a life back that I can feel OK about" model of recovery

There is a new model of recovery that's beginning to surface. As is often the case, while it's been held at some level by our clients forever we mental health professionals have been slow to catch on. The model simply defines recovery from mental illness in terms of the subjective quality of life that the individual is able to achieve. For many patients feeling good about their life again is the only recovery goal that makes sense.

In this model there is a recognition that many of the severe mental illnesses are based in changes in the way that the brain is structured. Implicit in that understanding is an awareness that most mentally ill people will not become "normal" after having their brain chemistry readjusted - and that this would not be a satisfying goal for many people in the first place.

When we can accept the fact that humans come in all sorts of forms and that everyone has something wrong with the way their brain is structured the clear delineations between those that are defined as mentally ill and those that are defined as mentally healthy begin to fade away.

This new model recognizes that symptom control alone does not equal recovery. Controlling symptoms may be very helpful - even essential - if someone is to establish a satisfying life after the onset of mental illness but it's never assumed to be enough. There is still the work of accepting the fact that life probably won't turn out as one originally dreamed. Residual symptoms such as reduced stress tolerance, difficulties with motivation, or reduced cognitive abilities have to be recognized and planned around.

Medications must be weighed in terms of both their positive effects and the unwanted side effects that often occur. Oftentimes a new social network must be established.

Recovery now becomes a process, one that looks different for each and every person. There is no expectation that progress will be linear or that its pace will be determined by the efforts of a helping professional.

Becoming truly responsible for one's own life and the direction that it takes is an enormous task for any human so it's not surprising that this sort of recovery from mental illness is not easy to accomplish.

Obstacles to recovery from schizophrenia

When concepts of recovery expand beyond the relative absence of symptoms it becomes discouragingly obvious that the list of obstacles to recovery is enormous. Residual problems that may exist after optimal medication therapy, side effects of treatment, and idiosyncrasies of our mental health system may combine in a way that may make reestablishing a life that feels good seem all but impossible.

One of the results of the current approach to psychiatric diagnosis is the common assumption that if the classic symptoms that serve as the basis for our diagnostic criteria aren't present then the person must be free of symptoms. Unfortunately, we're learning that nothing could be farther from the truth. In any mental illness a variety of symptoms that aren't even considered in the diagnosis - and are rarely asked about by treaters - may prove to be more important to the person's overall functioning and quality of life than the voices, delusions, depression, or manic symptoms that are typically the focus of treatment.

Negative symptoms

It is now an accepted fact that "negative symptoms" of schizophrenia typically have a greater impact on how the patient's life turns out than do the "positive symptoms" such as delusions and hallucinations that usually characterize the disorder. These negative symptoms are often present right from the beginning of the illness, may be associated with pronounced structural brain changes, and usually do not respond robustly to medications. But, as important as these symptoms are, this is another area where the problems are commonly overlooked or misunderstood by treaters and families. Unfortunately, these symptoms are often viewed as a sign of laziness, character flaws, or "just not trying hard enough."

The term "negative symptoms" refers to brain functions which should be present but are reduced or absent as a result of the illness itself. Experts may quibble over whether any particular symptom should be listed as "negative" but it's unlikely that anyone would disagree that all of these problems are commonly encountered in schizophrenia. Nearly any of these symptoms may be seen in the other major mental disorders as well.

Even if one has limited clinical experience it doesn't take too much imagination to understand that any of these symptoms can be a deal breaker for an individual who is trying to establish a good quality of life after the onset of mental illness. But a few of these symptoms deserve special mention.

Anosognosia is one of the most pervasive problems that patients- especially those with schizophrenic disorders- have to contend with. If one's nervous system can't work in a way that permits accurate comparisons of changes in the self over time it may be impossible to ever really come to believe that a mental illness is even present. Without awareness of illness or the ability to tell when symptoms are present it is extremely difficult to develop strategies for illness management. Other people's efforts to help may be experienced as unwanted intrusions or attempts to take away control.

Cognitive problems don't show up in the diagnostic criteria for most mental disorders but may have more impact on how a life turns out than any of the more readily recognized symptoms. A two standard deviation drop in I.Q. is common with the onset of schizophrenia and may even - depending on premorbid intelligence - effectively put someone into the mentally retarded level of functioning. Memory problems are common throughout the major mental illnesses - even before treatment effects are considered. Difficulties in abstract thinking may limit problem solving capacities as well as the ability to reflect on oneself. Family members, mental health professionals, and the patients themselves may all overlook or underestimate the impact of the illness on these basic cognitive capacities, with predictable results.

Aprosodias are neurologically-based problems with expressing or deciphering emotions through speech, gestures, or facial expressions. The actual content of the words we use is only a small part of human communication. Nuances of meaning, irony, and humor all depend largely on our ability to grasp the feelings and intent behind the words. When people can't understand what others are likely to be feeling or truly communicating - or can't attach recognizable emotional content to their own communications - human interactions can become ineffective or overwhelming. Experiencing empathy with other people may become impossible. Clumsy attempts at socialization may give way to near- total isolation. And while this type of problem is quite common is schizophrenia and not at all unusual in the affective disorders it's rarely discussed, recognized, or planned around.

Sensory integration problems may dramatically affect a persons ability to function but patients may go through their entire lives without anyone recognizing or helping to deal with them. For some people with schizophrenia the softest sound can reverberate through their head like a cannon blast. A light touch or the warmth of a shower may put them through the roof. Fluorescent lights can be dizzying. Common smells can evoke intense feelings of disgust.

While a variety of strategies can be helpful in dealing with these quirks of the sensory system, unless a client is fortunate enough to be assessed by a knowledgeable Occupational Therapist it's unlikely that these problems will ever be noticed. Instead, patients may try to moderate their incoming stimuli through the only strategies that they know. Staying in bed with the covers pulled up or continually rocking back and forth in a chair are seldom conducive to recovery.

Avolition

Problems with motivation or will are among the most important issues that anyone with schizophrenia must deal with. But these problems are so common in people with mental illness - regardless of diagnosis - that the fact that they can be a direct result of schizophrenia itself may not be appreciated.

Few of us have to look outside of our own skin to find examples of problems with motivation. We often forget that every time that we tell ourselves to do something - whether it be dieting, exercising, engaging in productive activities, or whatever - there is always a part of ourselves that rebels against the directive.

During any January health clubs are filled with well-meaning people who have commanded themselves to do things differently this year. By February it's easy to see which part of the self is more powerful. Humans are, by nature, so resentful of being told what to do that we even rebel when it's ourselves doing the ordering.

It's a rare human who can set a goal for himself, then pursue it with unbending and unambivalent intent. That sort of ability requires a singleness of purpose - an alignment of will, energy, focus, and desire - that few of us possess. So it's no surprise that people with schizophrenia or other severe mental illnesses would have more than their share of problems in this area. Fragmentation of the self, an inability to formulate or hold goals, and a generalized lack of energy are common. Ambivalence - the inability to make up one's mind about anything - is such a regular feature of schizophrenia that it once ranked as one of the four cardinal features of the disorder. And these are just innate facets of the disorder. Throw in the effects of demoralization, sedation, repeated failures, and people constantly urging them to do more than they able and one wonders how anyone with schizophrenia manages to get up in the morning.

Of course many other problems can stand in the way of recovery from schizophrenia.

Revenge fantasies are an obstacle that we almost never consider. But when our research group tried to systematically inquire about the mental life of a group of very ill schizophrenic patients we were surprised to discover that fantasies of revenge occupied a great deal of their thoughts. That's not too surprising when one thinks about it. Most of these people spent their childhood and adolescence on a relatively "normal" life trajectory, only to find themselves on a completely different path in young adulthood. Previous dreams of the futures that they might achieve were suddenly unrealistic and beyond their grasp.

Since so many never came to terms with the fact that they had suffered a severe mental illness or had any idea what this really meant it was natural that they'd conclude that someone had done something to them. When people spend much of their mental life trying to think about how they'll get back at their imagined tormenters it gets in the way of making accurate assessments of their situation and what they might realistically do about it.

Paranoid certainty is a related condition. People with these disorders frequently are convinced that their way of seeing things is the only way that has any merit. Trying to talk them out of their convictions is rarely productive, no matter how great the temptation to do so. Helpful therapists will often focus instead on exactly how these people reached their conclusions. What was the evidence that lead them to become so certain that people were tracking their whereabouts with depth finders? Could there have been an explanation that was overlooked? Was this a theory or a fact -and how can one tell the difference?

If the therapist presents himself as the guardian of reality and tries to convince the patient to abandon their delusional beliefs on those grounds the efforts are doomed to fail. When some semblance on an alliance can be formed - with a recognition up front that the therapist may be wrong too - it can sometimes become safe enough for the patient to consider new ways of understanding things. And new ways of understanding things are usually necessary if a person is to make progress towards a new way of living.

Obstacles to recovery in other mental illnesses

Hopefully, the emphasis on schizophrenia found throughout this work can be understood and forgiven. Schizophrenia is such a common disorder and affects so many mental functions that it's easy to assume that once one understands this disorder all of the other ones will fall nicely into place. But a simplistic approach like this doesn't do justice to the obstacles that clients with other disorders may face as they try to recover from their illnesses.

Bipolar Illness

Because bipolar illness is defined as an episodic disorder there is always a tendency to believe that the person will be essentially "normal' between the periods of mania or depression. And, indeed, some people do seem to be free of symptoms when their mood has returned to baseline. But those "classic manic-depressives" that return to normal lives and jobs between their occasional episodes of altered mood are becoming increasing rare in our public mental health systems. Residual symptoms at baseline, complicating conditions such as substance abuse or legal problems, and difficulty determining when one episode has ended and another has begun are all much more typical of severe bipolar illness these days.

Some of the blurriness between episodes is understandable if one looks at bipolar illness itself. While historically defined as a disorder characterized by shifts in mood from highs to lows, another way to conceptualize Bipolar Disorder is as a primary disorder of self- esteem regulation. Certainly moods shift from the highs of mania to the depths of depression but it's unclear whether the moods change first or in response to underlying changes in the sense of self. What does become obvious is that many people with bipolar illness have very unstable self-esteem even at their baseline. As a group they tend to be more self centered and insecure than people without the disorder.

People who have experienced mania often find themselves missing it - or at least elements of it - when the episodes have ended. While people are manic they may have increased energy and alertness. Creativity may be enhanced. The need for sleep is dramatically reduced. A grandiose sense of self importance and superiority to other humans is very common.

People may believe that they have a special mission in life or an exalted relationship with their God. Personal flaws or shortcomings are easily overlooked. Thoughts and speech come rapidly. Sexual impulses may be heightened. Mood can be euphoric or elated. Many people without mental illnesses pay good money to take drugs that mimic some of the feelings characteristic of mania. It's no wonder that some patients with bipolar illness long for those symptoms after they've passed, especially if their ordinary life feels boring, lonely, and unimportant by comparison.

The diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder is dependent on the presence of one or more of these episodes during a person's lifetime and much of the treatment efforts certainly center around controlling and preventing manic symptoms. But the actual periods of mania are usually not the biggest obstacles standing in the way of recovery in this disorder.

A little known fact is that most episodes of mania will resolve on their own, without treatment. The average untreated manic episode lasts somewhere in the neighborhood of seven weeks or so. Resolving mania with medications typically takes about four weeks. And people can go for years between episodes of mania. It's what happens when these people aren't manic that usually present the greatest problems with establishing a satisfying life.

Longing for the mania, mourning its absence, and even trying to recreate it by discontinuing mood stabilizers or abusing stimulants are all common problems among people with bipolar illness. Those feelings of energy, superiority, and self-importance can seem pretty attractive when one is forced to return to a reality that includes emptiness, despair, and loneliness. One of the common complaints that people taking mood stabilizers often voice is a dramatic reduction in their feelings of creativity. The medications can also cause sedation, weight gain, lethargy, and an overall feeling of mental dullness.

Suggesting that people with bipolar illness take mood stabilizing medications for the rest of their lives to reduce the statistical probability that mania will come back can seem like the most reasonable thing in the world to psychiatrists and other mental health professionals. In fact that approach is seldom questioned. And using more than one medication at a time to keep those moods stable is becoming more common than just giving one of them.

But the reality of the situation is that the average person who is prescribed a mood stabilizer in this country takes it for something like 57 days. It seems clear that this is an area where the patient's ideas about what recovery means to them don't square with the psychiatrist's recovery models.

Depression

Symptoms of depression are by no means limited to Major Depressive Disorder. Certainly depressive episodes are often more painful and problematic for people with Bipolar Disorder than the manic periods. Depressive episodes can present important obstacles to recovery in just about any of the major mental disorders. Whenever people experience too much stress, anxiety, loss, or even ongoing physical pain depressive symptoms can arise. And the impact of depressive symptoms can go far beyond the sad mood or decreased energy that characterize our ideas about depression.

Think of the amazing power of the placebo effect. Positive beliefs and expectations can have such an impact on how people function that the drug companies are hard-pressed to find medications that surpass placebos. It's easy to overlook the fact that the same process can work in reverse. It's not a stretch to say that depression represents an "anti-placebo effect."

Hopelessness is a core component of severe depression, regardless of whether the person has "Major Depression" or the feelings are a complication of another illness. And hopelessness carries with it a conviction that things will not get better, oftentimes in company with beliefs that the individual is bad, unworthy, or somehow not deserving of relief. Those types of feelings can have the same degree of impact on the reality that a person creates and experiences as do the positive beliefs and expectations seen in the placebo effect - it's just that they carry the person in the other direction. Believing that life is terrible and that recovery of a satisfying existence is impossible can readily become self-fulfilling prophesies.

Many people who are depressed struggle with suicidal thoughts and impulses and these present problems that go beyond the actual risk of harm to the self. No one makes progress towards recovery if they're repeatedly being admitted to psychiatric wards for their own protection. And when the main choice before a person is whether to die or continue living that doesn't leave much mental space for trying to find a way to live the best life possible.

Anhedonia is typically thought of as a complication of schizophrenia but it's surprisingly common in many of the psychiatric disorders. Anhedonia refers to a reduction in one's ability to experience pleasure. It often seems to have a biological basis but we're quick to forget that the experience of pleasure must be rooted in brain systems that can go haywire just like any other.

What could possibly have a more deleterious effect on a person's efforts to establish a rich and gratifying life than an inability to experience pleasure? But this is an area that we psychiatrists usually overlook. Many patients will go years in our mental health system without anyone even inquiring about their capacity to experience good feelings. We sometimes focus so narrowly on symptom control that we ignore the absence of the sorts of positive feelings that seem necessary to make life tolerable for anyone.

Curiously, the medications that we give to depressed people can present their own barriers to recovery. While they may provide welcome relief from feelings of anxiety and depression for a great many people, they can have side effects that we rarely consider when we think about how to help them move towards recovery. The relative "disconnection" between thought and emotion that often results from taking our antidepressants can, in practice, result in a person not caring about things in the way that they did before. It becomes harder to make real changes in the way we live our lives if our brain is telling us that nothing really matters much. So depression and its treatment can impede progress towards a richer and more satisfying life.

Some non-illness related obstacles

Anyone who works with severely mentally ill people in the community is well aware that these people commonly face enormous obstacles to recovery that really don't have much to do with the illnesses themselves.

Poverty is far too common among our severely mentally ill citizens but it's easy to overlook its dramatic impact on people's lives. Because in goes hand in hand with serious mental illness we have a hard time determining exactly which problems are a result of illness and which arise from plain old poverty.

Who among us could make progress towards building a better life if we were forced to subsist on an average of about 600 dollars per month? When we look at people without mental illness who live that far below the poverty line we don't see too many of them strategizing about how to better their condition.

When people are this poor it's natural that they're just trying to get by from one day to the next. Many battle hopelessness and despair every day. If there is anything that can make them feel better for even a little while many will grab at it immediately, even if it might make things worse in the long run. Planning for the future is a luxury limited to those who can count on getting through today.

Of course the straw that many poor mentally ill people grab at is substance abuse. It's been estimated that at least half of all seriously mentally ill people "abuse" illicit drugs or alcohol and that figure may actually be on the low side. There are so many factors that can converge to lead these people to abuse drugs that it's a wonder that any of them remain sober.

Our profession tells them that their brains have a chemical imbalance and that they need to take medicine to correct it. But when they take in chemicals that actually do make them feel better in short order we tell them that they've crossed a line into the "bad chemicals". As one patient who was prone to drug abuse so succinctly put it, "frankly, I like the way my chemicals make me feel a lot more than the way yours do."

When a person feels lousy most of the time as a result of brain problems, poverty, social isolation, or an absence of meaning in his life taking in a substance that quickly changes the way that they feel has enormous appeal. Sharing a drink or a joint can also be the only setting in which they can comfortably socialize with other people.

We mental health professionals are often prone to using moral arguments in an attempt to persuade patients to stop using drugs. But many of these clients are well aware that we can be a tad hypocritical in this area. And, as Mark Twain once said, "morals are for those with a full belly". Many of our severely ill clients are a long ways away from being "full"-both literally and figuratively.

We saw elsewhere that monkeys who were put into crowded conditions or subordinate social roles were much more likely to abuse cocaine than monkeys who had private cages or higher social status. The relative absence of adequate housing for severely ill people certainly recreates similar issues and problems. Overcrowding, social isolation, and stigma can all present severe impediments to recovery, even when they don't contribute to a pattern of substance abuse.

In actuality, most of these people don't even consider stopping drugs unless there's something in it for them to do so. When we can honestly try to convince people that their lives will be better if they're not complicated by substance abuse some people may be curious enough to listen to us. If we can truly help them to move their lives in a direction where they'll have something to gain by remaining abstinent - and something to lose if they use - many of them will make changes in their pattern of substance use over time.

When the focus is really on how to make their lives better people are generally willing to consider just about anything.

Unemployment is a huge obstacle to recovery for some patients. Somewhere in the neighborhood of ten percent of severely mentally ill clients work, despite findings from the "evidence based practice" literature that clearly affirm the importance of decent jobs for these people. In addition to the income that work provides, employment is an important contributor to self-esteem, identity, and social status. When people have nothing productive to do boredom, substance abuse, and hopelessness can readily result. Our mental health system clearly needs to find new and creative ways to provide meaningful work for the people that we're charged with caring for.

The building blocks of recovery

As has been stressed throughout this book, our social service system is not set up in a way that really promotes recovery from mental illness, regardless of the noble goals that are often voiced by the people in charge of it. For recovery to take place some very basic things must be in place and we don't do a very good job of providing them yet.

As one observes large numbers of mentally ill people over time one inescapable conclusion emerges: Almost no one makes significant progress towards recovery until they have a living environment that meets some simple requirements. Foremost among them is the need to have a stable place that the individual can call "home". In our current system this goal can seem impossible to achieve for some people.

The basic assumption is that mentally ill people will be transferred from place to place depending on the level of symptom or behavioral control that they exhibit at any given time. Frequent transfers between group homes, hospitals, apartments, and half-way houses are commonplace. Many clients live in several different places within just a year's time. It's easy to forget that very few people without mental illnesses could function well if they were never in one place long enough to get their feet on the ground.

So housing should be long-term, stable, and able to respond to variations in a person's clinical condition without having to move them to a new environment. But, of course, that's not enough. The living environment must also be safe enough so that the individual doesn't need to have hormonal stress responses activated continually. Mentally ill people are often left to live in situations that would make any sane person anxious. High crime neighborhoods, poverty, and overcrowding are all too common. No one begins to recover while their brain must deal with realistic fears that demand activation of "flight or fight responses".

While safe, long term housing is a prerequisite, even when it's available there is still no guarantee that recovery will take place. For life to become satisfying and meaningful an individual must find something or someone outside of themselves to become connected to. Without a connection to the real world - a sense of belonging to the greater human community - it's all too easy to live in the isolation of one's own mind. Hobbies, friendships, work, art, and pets are just a few of the options for finding something to love- but there must be that something.

People may find themselves becoming uneasy as they contemplate this model of "recovery" for the model brings into question the whole idea of what makes any life satisfying and meaningful. We Americans are at a stage in our development where clear answers to this question may seem evasive. The simple directives and rituals previously supplied by religion no longer feel adequate for many of us but there has been little offered up to replace them.

We are, as a people, becoming increasingly anxious, uncomfortable, and prone to depression. We're driven by forces that we barely understand. While we're preoccupied with status, sexuality, and possessions none of these things are enough to make our lives feel complete.

So defining recovery from mental illness as "developing a life that one can feel good about" may seem like setting the bar impossibly high. But would any of us be willing to settle for anything less than that for ourselves? Does any other recovery model truly suffice for our mentally ill citizens? These are questions of more than intellectual importance. The beliefs that we hold about recovery from mental illness impact every aspect of our mental health system. More importantly, they shape the expectations, behaviors, and lives of the people that suffer from these disorders.