Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

Problems with Psychiatric Diagnosis

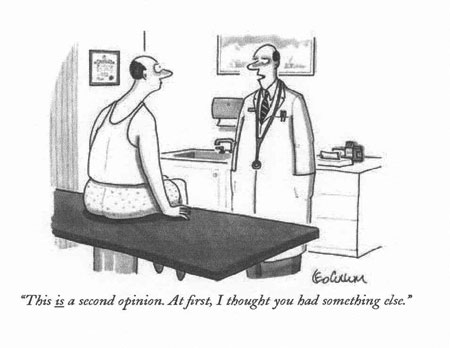

When one sits down with consumer groups, families, or patient advocates one of the most common complaints that we hear voiced today is that "every time someone sees a new psychiatrist they get a new diagnosis." It is easy to see why this could be a bit disconcerting. Imagine going in to see your Family Practitioner and being told "it turns out that you don't have diabetes after all - you have multiple sclerosis."

As strange as that scenario sounds, it's not an uncommon one for psychiatric patients. Many patients carry each of the diagnoses of Schizophrenia, Major Depression, Bipolar illness, and Schizoaffective Disorder at some points in their lives. A recent review of the case of a woman who had committed suicide found that her psychiatrist had diagnosed her with all of these disorders within the past year. It's a rare patient who carries the same psychiatric diagnosis throughout their lifetime.

A shifting approach to diagnosis can hardly be expected to build confidence in one's psychiatrist. People, rightfully, expect that their Doctors will make a clear, reasoned diagnosis of their condition and that treatment will follow accordingly. Our field's inability to agree on what disorder an individual actually suffers from is held up by some as confirmation of their belief that psychiatry is just a bunch of pseudoscience at best or, at worst, a profit-driven business.

Many patients become confused about this issue. They want to trust and believe in their Doctor and don't really know much about how diagnoses are made. So they frequently will say things like "my Doctor says that I am schizophrenic and bipolar". Explanations about why something like this is not technically possible are not always welcomed. The patients are, understandably, invested in believing that their psychiatrist is an expert at what he does. And those labels can readily become a part of the way they think about themselves too.

Some people may ask whether all this fuss about attaching labels to people is really necessary. That question is becoming an increasingly legitimate one. Even some psychiatrists are beginning to publicly speculate about whether the severe mental disorders might exist on a spectrum rather than as discrete clinical entities.

The whole point of making diagnoses was originally to improve patient care. People who had the same diagnosis were supposed to be suffering from pretty much the same constellation of symptoms and problems. We assumed that their illnesses had the same causes. A sound diagnosis is also intended to provide information about the prognosis that a patient suffering from any given disorder is likely to have- what course the illness is likely to take, whether it's likely to get better or worse over time, the likelihood that it will run in families, and so on.

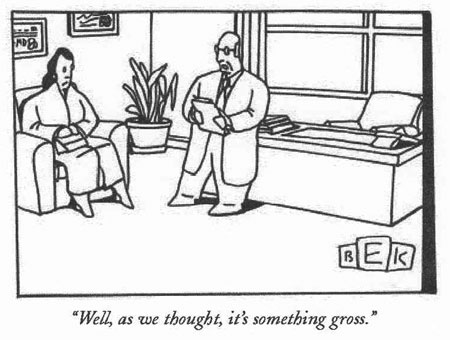

We like to think that the diagnosis that we make will also help to predict what sorts of treatments will or will not be effective for the condition. It's pretty easy to argue that our current approach to psychiatric diagnosis falls far short in each of those areas.

What might a diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder really mean?

Look at the example of Bipolar Disorder. A wide range of opinions exist among psychiatrists as to which groups of symptoms should trigger this diagnosis. Some psychiatrists are now accused of believing that essentially everyone with a mood disorder is "Bipolar". They'll argue that if the requisite manic symptoms don't appear to have been present that must be because the person didn't remember or interpret a period of unusually good mood as evidence of a manic episode. Some shrinks will even claim that if a person with depression hasn't had a manic episode it's only a matter of time until they do. So they diagnose Bipolar Disorder based on assumptions about symptoms that they think the person will have in the future.

The implications of this kind of confusion are considerable. These days if one were to take a representative sample of public sector patients who have been diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder it will become clear that a wide variety of problems have lead to the application of that label.

Some of those patients will have the typical disorder that we used to call "Manic- Depression". They'll have occasional manic episodes characterized by elevated mood, increased energy and talkativeness, a decreased need for sleep and so on. One of the strangest things about this disorder, though, is that the "classic" manic patients now seem to be quite rare. The quick witted patients with the giddy moods appear to have been replaced by the "irritable manics" that were more recently admitted to the diagnostic grouping. Of course these patients are very likely to have depressive episodes too, although those aren't technically required for the Bipolar diagnosis. Their disorder commonly runs in their families, the patients are typically stricken with it in their early twenties, and the frequency of the episodes of mood disturbances often increases as the years go on. Mood stabilizing drugs may help to reduce the number of manic or depressive episodes, as well as their severity.

That same grouping of "Bipolars" is almost certain to have a number of patients who would never have had a manic episode were it not for drugs that destabilized their brain's mood regulation systems. Most commonly the offending agents are stimulant drugs of abuse such as cocaine or methamphetamine but sometimes it's actually antidepressant medications that trigger the mania.

Some of the allegedly "Bipolar" patients will really have a personality disorder.

Borderline Personality Disorder has mood lability as one of it's cardinal features. Depressions are common and occasional patients will have brief episodes of mania that don't qualify for the actual diagnosis. Those patients may also exaggerate or misrepresent their symptoms on occasions when doing so is necessary to get help. But some psychiatrists won't even diagnose personality disorders anymore, at least as the primary diagnosis. It's easier to conceptualize the person's problems in terms of bipolar disorder because then the psychiatrist has some clear treatment options to offer. And the bipolar diagnosis may be much more palatable to the clients than being called "personality disordered". When you're "Bipolar" there aren't the same judgments made about your character and there may not be the same assumptions about personal responsibility for your behavior.

A few of the people in our little group of diagnosed "Bipolars" would actually turn out to have schizophrenia if more details about their history were available. Episodes of depression are extremely common in schizophrenia and a fair amount of these people have periods of agitation, sleeplessness, grandiosity or even classic mania. Some psychiatrists will, understandably, always error on the side of calling people "Bipolar" rather than diagnosing schizophrenia though. As one shrink put it "it just sounds so much nicer to say that they're Bipolar".

Strangely enough, a couple of the patients in that collection of "Bipolars" may not even have a mental illness at all. Some will present with complaints of depression or suicidal thoughts as a way to obtain housing or other entitlements. When historical information is inquired about they may endorse a history of a lot of different symptoms in order to bolster their claim of mental illness. And once something gets written in someone's chart it can develop a life of its own. Professionals years down the line may see that manic symptoms were documented or Bipolar Disorder was diagnosed and those "facts" get carried on into the current diagnostic formulation without much question.

So a common diagnostic label such as Bipolar Disorder can mean a wide variety of things in actual practice. Our efforts to identify a group of patients with similar symptoms, causes, prognoses, and responses to treatment, is clearly breaking down. Of course a cynic may ask "so what? - they all get the same combination of medications anyway". Point well taken. But if we are going to make diagnoses - attaching labels that follow people everywhere and even shape the way they come to think about themselves, their lives, and their futures, shouldn't we take the matter seriously?

Is Every Human Problem The Result Of A Diagnosable Mental Disorder?

We are now faced with a situation where nearly every conceivable human problem has been given an official diagnosis and a five-digit diagnostic code. There are nearly 300 separate mental disorders defined in the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. If it's true that we humans exist as either "lumpers or splitters" it's pretty clear which group has won out when it comes to psychiatric diagnosis. Maybe this is all getting too complex and confusing for anyone to keep up with. We've had four successive diagnostic manuals released since 1980 and the criteria and names for many of the disorders have changed with each new edition.

Busy psychiatrists often don't take the time to read or understand the changing diagnostic criteria. In practice, most of us only use several favorites from the hundreds of diagnoses available. Of course we tend to diagnose conditions that we think that we understand and that we feel comfortable treating. And we favor making diagnoses that trigger ready reimbursement from insurance companies and government programs.

These days there is no guarantee that the psychiatrist will even make the actual diagnosis. Nurses or social workers may provide the diagnosis after their intake assessments and the psychiatrist then signs off on it for billing purposes. Busy clinics can provide care to more people - and increase revenues - if scarce psychiatric time is not tied up with diagnostic interviews. The obvious problem is that many of the professionals who end up doing the actual diagnosing have not had much training or experience in the process.

We shrinks are fond of telling stories about how things were different back in our training days. "The days of the giants" as it were.

At the New York Hospital- Cornell Medical Center in the early 1980's we had a tradition of attending ninety-minute case conferences in which the care of an individual patient was discussed at great length by a group of psychiatrists and trainees. In these meetings there was so much emphasis placed on making sure that the patient had been given the correct diagnosis that sometimes we had little time to discuss anything else. The idea was that all treatment flowed from the person's diagnosis. Attaching the wrong diagnostic label would certainly lead to far-reaching negative consequences.

Of course those were times in which a psychiatrist would typically spend at least a couple hours performing diagnostic interviews on new patients, then see them several times per week for fifty minutes. It was just expected that we'd know our patient's histories and symptom profiles in intimate detail. The situation is very different today, particularly in our public mental health sector. A number of factors make psychiatric diagnosis a much more uncertain undertaking these days.

Problems with the Modern Diagnostic Process

One problem inherent in modern psychiatric diagnosis is that it's typically based on answers to a series of "yes or no" questions, usually about the presence or absence of various key symptoms. Some of the older, more psychotherapy - oriented psychiatrists have protested that diagnosis has been reduced to a "Chinese menu" or "comic book" approach. Whether there's truth to their assertions is open to debate.

The opposing view would say that we must have clear, objective diagnostic criteria that don't require a lot of intuition or psychodynamic understanding if these diagnostic criteria are to be reproducible across many clinical settings. But regardless of one's views on the subject, it's increasingly clear that a great many things can go wrong with our diagnostic process today.

Time is the biggest current obstacle to making good diagnoses. Psychiatric time is a scarce and expensive resource in our clinics and hospitals these days. There is no time for lengthy diagnostic interviews. Thirty minutes with a new patient is a luxury in some settings. The catch is that psychiatric diagnosis is based on a longitudinal perspective of the person's life and symptoms of mental illness. You need to know basic things like when the illness began, what symptoms have been characteristic, whether they were episodic or continuous, and if they were related to things like substance abuse or medical problems. Family histories are often informative. The relationship of symptoms to stressful life events or the types of problems necessary to obtain entitlements should be understood to the fullest extent possible.

To really get the right sort of historical data it's usually necessary for the Doctor to review the patient's medical records from previous treatments. This is not easy to accomplish these days. The records might not be available or obtaining them might be too difficult. Even if they are available it's hard for psychiatrists to bill for the time spent in reviewing them. And there are usually patients waiting, with real clinical needs that may supersede the importance of chart reviews.

One main weakness in the current approach to diagnosis is that it usually depends on the patient to provide the answers about whether various symptoms have been present, and for how long. This can be problematic in many cases. Sometimes the patient does not really understand what we're asking. We may use words or concepts that are foreign to them. Everyone who has been around psychiatrists has witnessed us embarking on long-winded technical explanations of things that make sense only to us. That may add to our mystique but fuzzy communication does not help to create clear diagnoses. A good psychiatrist will take the time to check with the person to see what their understanding is of what we are saying or asking.

Sometimes the patient knows exactly what symptoms we're inquiring about but they temper their responses for various reasons. Patients often know what symptoms sound "crazy" or will lead to a psychotic diagnosis. For example, people with Paranoid Schizophrenia are often quite adept at presenting as "sane" during diagnostic interviews or even psychological testing. They know the sorts of symptoms that they should not endorse and their denials of "voices" or other psychotic symptoms are usually taken at face value.

Oftentimes a fear of our antipsychotic medications drives this tailoring of their clinical picture. Some people are afraid that if they reveal what their inner world is really like they will have their medication doses increased or be forced into involuntary treatment. Others dread the very real stigma that is attached to schizophrenia and the other psychotic disorders. Losing jobs, housing, or custody of one's children are always realistic possibilities for people with severe mental illnesses too.

We have seen that a phenomenon called "anosognosia" is very common among people with schizophrenia. Briefly stated, the idea is that the mental illness itself prohibits the person from realizing that he is ill. Forming complex representations of themselves as they exist today, then comparing them with representations of how they used to be before they became ill, is one of the most difficult things for people with schizophrenia to do. So oftentimes when they deny symptoms of their illness to psychiatrists they are only telling the truth as their nervous system presents it to them. Asking them to truly recognize and describe symptoms of their illness may be akin to asking a color-blind person to see the color green.

Strangely enough, some patients exaggerate symptoms of their illness during diagnostic interviews. They may be homeless, hungry, and savvy enough to know that if they're going to get a scarce hospital bed they'll have to present themselves as very sick or very dangerous. In Minneapolis these days there is so much pressure for acute inpatient psychiatry beds that patients are often transported to distant cities or even neighboring states for treatment. In other places those same people might not receive any kind of help at all.

Many street-smart clients now know (and occasionally confess to their psychiatrists) that one common way to get admitted to hospitals is to "say that I'm hearing voices telling me to kill myself". It is a sad state of affairs when our mentally ill people have to go to these lengths to get treatment (or more commonly food and shelter) but this is the reality that we currently must deal with.

Sometimes patients magnify symptoms or problems in order to receive, or continue to receive, disability benefits. For example, the diagnosis of Major Depression is a common current justification for receiving Social Security Disability checks. While true Major Depression is typically a self-limited illness - one that usually got better on its own even before the days of widespread antidepressants - many clients will literally receive disability benefits for decades because they have been diagnosed with Major Depression.

This also points out the "political" nature of some of our diagnostic practices. Back in the 1990's it was decided that people with primary Chemical Dependency diagnoses would no longer be able to receive Social Security Disability checks on the basis of their addictions. Many of us in the public psychiatry sector braced ourselves for what we knew was coming...

Chemically Dependent people now have to have the diagnosis of a mental illness to continue receiving disability benefits. And Major Depression has been the most attractive candidate. It does not carry the same degree of stigma as some of the other disorders. After all, fully 15 percent of the population gets depressed at some point in their lives. Plus, the diagnosis of Major Depression today requires only that you answer "yes" to five of nine questions about whether various depressive symptoms are present. And it's pretty easy to figure out how to answer the questions.

Few would now question the fact that predictions about Chemically Dependent people flooding the existing mental health programs have proven accurate.

This candid appraisal of what people will sometime do to get benefit checks or hospital beds may seem a little too cynical for some advocates of the mentally ill. But we shrinks sometimes hear about how patients will even go to the library or the Internet to see what symptoms they need to endorse to get a particular diagnosis. Most of us do not hold their actions against these people. Sometimes we can even admire their resourcefulness.

Human beings are a lot like ants and crows. We can live just about anywhere. If there is an available environmental niche that provides food and shelter to humans you can bet that someone has found it and is using it. Again, if there is any shame here it's that we've put people into positions where these sorts of options and behaviors look better than anything else that they can see as available for themselves. We certainly have the resources to provide a decent standard of living and good medical care for each person in this country if that were consistent with our values and beliefs.

Some other commonly misdiagnosed conditions

The list of candidates to be included in this section seems endless. Let's look at just a few common examples to see how these problems with diagnosis get translated into modern psychiatric practice.

When we diagnose schizophrenia psychiatrists are also supposed to specify which subtype of the illness the person suffers from. The choices are paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, undifferentiated, and residual. In theory, each of these types differs in terms of the symptoms that are present and there are some differences in prognosis occur as well. Yet some psychiatrists never diagnose any other type of schizophrenia except for paranoid type. This may not have a huge impact on the person's treatment (since we give everyone the same medications anyway) but the reasons for this diagnostic mismatch are informative.

Paranoid Schizophrenia is a term that is intended to separate out a particular subgroup of people with schizophrenia. These are people that often have a later onset of illness and the prognosis for the disorder is generally not as grave. In some cases these people may even have a nervous system that is structured relatively "normally" but then something happens to it that results in the appearance of characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia. In some people the breakdown of a particular protein in the nerve cell, termed a "tau protein" may be involved.

At any rate, the intention of the committees that define these disorders was to create a diagnostic category for a type of schizophrenia that was different than the rest in its symptoms and prognosis.

Paranoid Schizophrenia is defined primarily by symptoms that are not present. In DSM IV TR it requires a "Preoccupation with one or more delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations". No problem there. The other requirement is that "None of the following is prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect". Most people with schizophrenia do have one or more of those exclusionary criteria and are not eligible for the Paranoid Type diagnosis.

In actual practice many psychiatrists still use "Paranoid Schizophrenia" simply to mean that the person has prominent symptoms of paranoia. Any or all of those symptoms that prohibit the diagnosis may be present but the Paranoid Type specifier is still given. A big part of this diagnostic mismatch results from the fact that many busy psychiatrists just don't read the new manuals or use the information within them in their day to day practice.

The real implications here have to do with the fact that the important criteria that research committees use in forming these diagnoses are not known or appreciated by the clinicians. We don't really understand how or why the experts determine these differences in diagnosis. So the fact that we don't spend a lot of time reading and memorizing them is not that surprising.

In this case the results of the misdiagnosis are usually not that severe. People don't typically receive different treatment or benefits because of the paranoid subtype. We may not be as able to provide good prognostic information if we clump everyone together as "paranoid type" but that's not an area of strength in the psychiatric profession anyway.

In other disorders the mismatch between clinical disorder and diagnosis carries greater weight.

A very common mistake in the public sector is the practice of adding "Axis II (meaning Personality Disorder) diagnoses to people with schizophrenia. People are given labels such as "antisocial", "dependent" or "borderline" in addition to the schizophrenia diagnosis. Some of us have a lot of trouble with this practice. The fact that it is wrong, and again reflects an inadequate understanding of the diagnoses involved, is only a small part of the problem (The DSM's do provide for the addition of a Personality Disorder diagnosis in cases where the person clearly had a personality disorder before the onset of schizophrenia - in that case we're supposed to specify that it was a "Premorbid" diagnosis).

In schizophrenia there are usually severe problems with the way that the brain is structured and hooked up during fetal development. Then, generally in late adolescence, the schizophrenic brain undergoes another massive transformation. Extensive amounts of gray matter are lost and it becomes difficult to find areas of the brain that still work normally. The person's very sense of self is eroded. Perceptions of the world and other people become distorted. Even basic mental tasks such as those allowing the person to have "will" or a sense of future may break down.

So in the setting of a dramatic brain problem that changes one's view of self and world, as well as limiting the behavioral responses available to a person, some psychiatrists are going on record as saying that the person has a "personality disorder" as well. This shapes the way that other professionals, family members, and even the patients themselves come to understand the patient's problems. It contributes to prevailing beliefs that there is really nothing wrong with these people or that they should just try harder.

To some of us, calling people with schizophrenia "personality disordered" as well seems like kicking someone when they're down. These people deserve better from their psychiatrists.

Sometimes we make errors in the disorders that we don't diagnose. An enormously important diagnosis in our culture is that of "Cocaine-Induced Mood Disorder" but that is one that we almost never see utilized in our public mental health systems. In the "Emerging model of mental illness" chapter we looked at the connections between a lower place on the social ladder, crowded living conditions, and a biological propensity for cocaine abuse. Every major urban center in America struggles with this problem nowadays. And now the closely related problem of severe mental disorders arising from methamphetamine abuse is moving from rural America to urban areas as well.

A key point in trying to understand the effects of these stimulant drugs of abuse is that they usually don't make a person psychotic or manic after just a dose or two. But with continued use they can destabilize important brain systems. Some researchers have termed this gradual destabilization kindling. Symptoms of genuine psychosis or mania can develop and they can be indistinguishable from those found in the non-substance abuse related disorders.

In many cases the only ways to tell if these symptoms are related to drugs rather than an underlying mental illness are a) to get good historical information about whether the symptoms arose in the setting of continued stimulant abuse or b) to treat the symptoms, then observe to see if they ever recur in the absence of stimulant abuse. The problems involved with this process are obvious.

Many times our patients don't accurately report the connection between drug use and their psychiatric symptoms. And why would they? Few people will willingly discuss their illegal behaviors with professionals to begin with. Then, if the symptoms of psychosis, mania, or depression result in the person becoming classified as "disabled" - and eligible for disability benefits that they wouldn't otherwise be entitled to - the incentive to honestly report drug use further evaporates. Psychiatrists are understandably reluctant to attribute someone's mental health problems to substance abuse unless they are very certain of the connection, especially if we know that it may result in the person becoming homeless.

The option of seeing if symptoms don't return in the absence of substance abuse is one that's hard to utilize. When we suspect that someone has psychiatric symptoms due to substance abuse the natural tendency is to refer them for "Chemical Dependency Treatment". This is getting harder to access as budgets devoted to public mental health are being slashed throughout the country. Even when people can get into good inpatient Chemical Dependency programs a predictable sequence of events frequently occurs.

The clients begin to look much better clinically. Psychotic symptoms abate and moods stabilize. Some of this may be a result of medications but the role of a decent environment that provides good nutrition, medical care, and the support for abstinence are extremely important too. Then, after the inpatient program is completed, the person is returned to an environment that usually includes poverty, a lack of productive activities, and lots of other poor people that are using drugs. Any gains that had been incurred in the treatment program are quickly lost.

The return to substance abuse eventually leads to another psychiatric decompensation, more medications, and even further confusion about whether the person would really have a mental disorder in the absence of stimulants. Anyone who works in public mental health has seen innumerable people that exhibit this pattern for years on end.

It's impossible to get a clear look at our diagnostic practices if we can't filter in the effects of race and poverty. Research has shown that the same symptom profile is much more likely to result in the diagnosis of schizophrenia if a person is black than if he's white. Powder cocaine doesn't carry the same implications as crack. And when our system insists that the report of certain symptoms are required for poor people to obtain housing or other entitlements we have to wonder to what extent our social programs actually shape the symptoms that people report - or actually experience.

So it's clear that the numerous problems with psychiatric diagnosis today have more than just academic implications. There are many social problems that will be hard to remedy unless we become much better at reliably determining who really suffers from what disorder. And these are just a few examples of the many diagnostic problems that we are struggling with these days.

We haven't even addressed the biggest culprit in the problem of psychiatric diagnosis. While the psychiatric profession has expanded its list of diagnoses to almost 300 disorders, in the public sector there has been an evolving movement to give everyone the same one. Schizoaffective Disorder has become a diagnosis that almost everyone with a severe mental disorder seems to get at some point in their life. The current diagnostic practices involving Schizoaffective Disorder are so pervasive and important that the next chapter will be devoted to that issue alone.

How Might Psychiatric Diagnosis Be Different in the Future?

Several systems changes may have to take place before the declining standards of psychiatric diagnosis are reversed. Simply putting an emphasis on allowing people to stay in their homes and adjusting the degree of services brought in to fit their changing clinical conditions will have a pronounced impact on diagnosis.

In our present system people are moved from place to place as a result of changes in their level of symptoms. Each place that they go to has its own paperwork requirements around diagnosis. And the different facilities rarely communicate well with each other. So at each stop on the circuit there is a new conceptualization of the patient's problems and opportunities for a new diagnosis - or misdiagnosis. A new "treatment plan" must be created, complete with new "goals" that the professionals must document for the patient (in truth, severely mentally ill people rarely think in terms of "goals and objectives"- this is another well-intended creation of administrators that may be far removed from clinical realities).

Current technology should allow a more permanent and complete record set to stay with the patient wherever he goes. This would allow ongoing data gathering and remove the need to reinvent the wheel every time the patient moves to a new place. Ideally, the client himself should have a great deal of input into the generation of those records and a sense of ownership of the contents. The charts are, after all, a documentation of their life and their psychiatric treatments.

Creating systems of care in which psychiatrists have long term relationships with patients will obviously help. Some of the Model Community Programs outlined in another chapter would build in ongoing relationships between professionals and entire groups of consumers. Allowing the Doctor to get to know people over time, and to be a part of their actual living environment, will provide a much different perspective on people's illnesses than can be obtained by infrequent office visits. Much richer and varied sources of information about how people actually function and what symptoms are really present will be available in these sorts of models. In the ideal case, the Doctor knows what the course of the symptoms is over time because he's had a chance to witness them first hand.

The changes in the Doctor-patient relationship that have been outlined elsewhere will go a long way towards improving diagnosis too. As the treatment relationship becomes more symmetrical, the process of diagnosis becomes more of a cooperative venture. The Doctor helps to educate the patient about the key symptoms that are involved in diagnosis and they try to determine together which label provides the best diagnostic fit. Matters of prognosis and options for treatment are openly discussed. It's always amazing to see how many patients in our present system do not have any idea what their diagnosis is or why their Doctor thinks they have a particular disorder.

In the current office-based practice models psychiatrists can do a better job of leading by example.

When we use shoddy diagnostic practices like calling everyone "schizoaffective", adding countless "rule out" diagnoses without actually doing anything to rule them out or confirm them, or neglecting the diagnostic criteria that we've all ostensibly agreed to use, we give other professional the wrong ideas about diagnosis. And when systems of care actually use nurses or other professionals to provide the diagnoses they should be honest about that. If these people are going to do the diagnosing we should train them specifically in the art of diagnosis rather than pretending that the psychiatrist is doing the work.

There are some computerized diagnostic programs available now and some of them aren't too bad. Their strength is that they ensure that all of the right questions necessary to make a sound diagnosis are asked about in a systematic fashion. But, like any approach to diagnosis, they depend on the patient's willingness and ability to provide accurate and honest answers. Without that honesty computerized approaches readily fall prey to the "garbage in-garbage out" phenomenon. A good diagnostic program is available at www.mentalhealth.com and can be used for one month for around twenty bucks. Since a single diagnosis can usually be made in an hour or less that month leaves plenty of time for diagnosing friends and family.

Of course many of us are waiting for the day when our diagnoses will be determined by improved technology in the brain sciences. If we can do specific tests that will tell us exactly what sort of disorder a person suffers from that would immediately clear up many of the problems around diagnosis. We may be surprised, however, to see that many of our current basic assumptions about diagnostic categories don't hold up well when accurate tests become available.

Perhaps in our lifetimes there will be sufficient technological advances in neurobiology and genetics to provide definitive diagnoses for each and every patient. If that day comes the same technologies will undoubtedly be able to tell us exactly which medications will allow each person to function at their best. These are the dreams and goals of every "biological psychiatrist."

There is genuine irony here though. If we get to the point where every patient can be given the optimal diagnosis and treatment through technology, the psychiatrist's role will change dramatically. Talking to people, helping them to better understand themselves, and trying to help them find optimal ways of living will be what's left for us to do once the machines can diagnose the disorders and determine the treatments. Once the pendulum swings fully towards a biological approach psychiatrists will once again be involved in our previous roles as psychotherapists and students of the human condition.