The Neurobiology of Housing

Kevin Turnquist M.D.

November 2003

The Problem

The problem of providing adequate housing for our mentally ill citizens isn't new. It has been with us since the onset of deinstitutionalization, despite the best efforts of several generations of mental health professionals. In many ways this situation is getting worse with time and the trend is likely to continue unless a very real paradigm shift occurs.

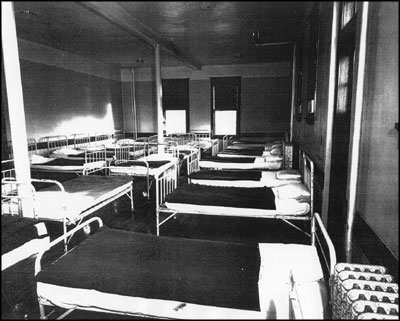

State Hospital Ward circa 1950's

Things weren't great for mentally ill people prior to deinstitutionalization either. Wards were crowded, medications were less effective, and patients were sometimes treated badly. The movement to relocate patients from large State Hospitals back into their communities seemed like the most humane thing to do at the time. In retrospect we can see that the movement, however well intended, left many people in far worse conditions than they had endured back in the asylums.When discharged from the large institutions homelessness, poverty, inadequate treatment, and social isolation awaited them.

We can attribute most of our problems with housing the mentally ill to some basic assumptions that were present at the very beginning of the deinstitutionalization movement. Perhaps most important and pervasive was the almost insurmountable human tendency to believe that other peoples' minds, even those of people with mental illnesses, work in a manner similar to our own. Schizophrenia and other major mental illnesses were believed to be "functional disorders" as opposed to the "organic" mental disorders. We have long assumed that once the hallmark hallucinations, delusions, and other severe symptoms were controlled with medication the individual should be pretty much "normal"- like us. The programs and strategies that we devised to care for mentally ill people were generally ones that made sense to us and -would work for us.

We assumed that once we released people from institutions they would promptly and willingly show up at outpatient clinics to receive their care. Of course they would take their medications regularly. Our assumption that they would return to "normal" living situations upon leaving institutional care was unquestioned.

This has essentially translated into an effort to put everyone into single occupancy apartments in mainstream buildings (actually, most non-mentally ill people don't really live that way though). As it became obvious that this wasn't working for many people with severe mental illnesses we've tried to beef up the services available in-home. Now if more help is needed we've created an army of workers who will come to the person's apartment. Operated case management teams and dozens of contracted vendor programs now exist.

We have created special waivers for the elderly, the brain injured, and people at risk for nursing home placement. Shopping, meal preparation, housecleaning , transportation to appointments, help locating work, day treatment, medication monitoring, and a host of other services are provided - whatever it takes to help the person to stay afloat in their apartment. This is a more humane system than what has existed before. Sometimes it works tremendously well for individuals. But there are a great many people who do not benefit from this system. Their neuropsychological deficits that remain even after effective medication treatment are often too extensive to be addressed by bringing services into the home for a few hours at a time. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that anyone will receive good medication treatment in our mental health system. And even if it's offered there is no assurance that clients will actually take these medications. Non-compliance rates with psychotropic medications often run at over 50%.

Of course there are a lot of other problems with this system. The array of apartments available when a person is getting 570 dollars per month for Social Security Disability Income or other entitlement programs is very limited. Many of these clients have "unauthorized detainers" (evictions) or other problems on their housing records that would immediately disqualify them for good apartments, even if they could afford them. Yet our system is based on the idea that these people will get apartments from regular landlords. The fact that those landlords almost always have other prospective tenants to rent to- people that are much more attractive as renters- is overlooked.

Given the current housing crunch, our clientele's general unattractiveness as tenants, and their poverty, it is natural that they would end up in the worst buildings and neighborhoods. The high turnover rate in these apartments is also understandable. Even on the occasions when decent housing is somehow arranged a lot of things can go wrong. Many clients are vulnerable to exploitation and quickly have their apartments taken over by drug dealers, other indigent people, or even family members, and lose their apartments as a result.

Studies find that over half of our mentally ill people abuse alcohol or street drugs (but curious double standards are often applied by helping professionals). Why wouldn't they use these things to try to feel better? What other sources of pleasure do they have in their lives? And what do they have to lose? Most non-mentally ill people don't quit using drugs or alcohol until they are facing some sort of negative consequences as a result of their use. Losing a job, relationships with loved ones, or their self respect are common motivators for people to become sober. But many of our patients don't even have these things to lose in the first place.

Drug and alcohol abuse and their associated behaviors often result in problems leading to eviction as well. Many clients have been given the false impression that if they decide to drink, or use marijuana or other drugs, they should stop their psychiatric medicines. So they end up dealing with the effects of substance abuse and the abrupt stoppage of their medications at the same time. The clinical triad of psychotic decompensation, medication non-compliance, and substance abuse is one of the most common causes of hospitalization and lost housing.

The day-to-day lives of mentally ill people living in these situations are often quite grim and empty. Many are afraid to leave their homes, especially after dark. The few apartments that are available to our impoverished clients are often run down and clustered in undesirable, high crime neighborhoods. None of us would choose this sort of life for our children.

Loneliness is an enormous problem for our clients. Even bringing someone in to the apartments for several hours per week leaves the person alone for the vast majority of their time. These are people who often have tremendous difficulties with human relationships. They do not initiate or maintain contact with others easily. They can be overwhelmed by closeness when it does occur. They are often shunned or stigmatized in their buildings. The hours that they are the most isolated, lonely, and anxious are often during evenings and early mornings - times when no mental health professionals are available and going out of their apartments is the riskiest. Recent studies have found that people who are lonely frequently do not sleep well. Lack of sleep only compounds their preexisting problems with brain functioning. A cycle of increased depression and anxiety or destabilization of psychotic or manic conditions, which in turn lead to further impairment of sleep, often results.

In reality, there are many people for whom living in scattered site apartments simply does not work. Problems with planning, foresight, judgment, impulse control, and substance abuse are just too tenacious. Yet many clients will often insist that they want an apartment and refuse to look at other alternatives simply because the other available options are so limited, and so distasteful to them.

The emphasis on holding individual, mainstream apartments as the goal for everyone carries a wide variety of associated problems. This system is extremely expensive. A single client can easily utilize $2000 -3,000 per month in waivered, in- home services in addition to costs for the apartment, food, and psychiatric care. The medication costs for these individuals can easily contribute another one to two thousand dollars per month. Even going grocery shopping can easily end up costing much more for the staff's time than for the actual food. Sometimes it is necessary to send two staff members out for even routine business with clients - either because of the client's own potential for misbehavior, problems with other people living in the buildings, or the dangerous neighborhoods that the apartments are located in. Many times when staff arrive at the apartment the client is not there and the visit has to be rescheduled. Fear of strangers, a belief that they do not really need services, and difficulties maintaining schedules are just a few of the reasons why so many times services are set up for our clients but have to be abandoned after only a month or two.

Compounding matters is the fact that the agencies that provide workers to come to people's apartments to help out are chronically short-staffed. Their workers are frequently underpaid and lack basic training about mental illness. These companies are in competition for employees with fast food restaurants and other generic, low paying jobs. There is an enormous amount of turnover in personnel and waiting lists for new workers are often lengthy. This instability is particularly difficult for our clients as they generally tolerate change so poorly.

For the many clients who can't manage to live independently, the options are often worse. The backbone of our housing system for the severely mentally ill in Minnesota are the "Rule 36 Facilities". These half way houses are charged with the task of preparing the client for independent living in the scattered site apartments. This goal is often impossibly difficult to meet. These facilities were only designed to keep people for nine months or so before having them ready for apartments. Recent changes have attempted to further limit the time a person can stay at these places to 90 days. Our half way houses are often poorly staffed and little actual therapy or preparation for independent living takes place. The neurolopsychological deficits that people have as a result of their mental illnesses are not the kind that can easily be remedied and even if learning takes place in one environment there is no guarantee at all that it will transfer to a new one. Plus, the clients are typically crowded into rooms with one to three other clients.

For many clients, the half way houses- though beset with problems- are the places that do the best in terms of providing the amount of staffing and supervision that the person needs to get by outside of hospital settings. But the clients have to leave in one way or another. This whole system depends on people leaving in fairly short order. While some people actually do move on to successful apartment living, Minnesota's Rule 36 programs have to rely on the fact that a great many clients will leave via hospitalization or eviction.

Other housing options are also beset with problems. Board and Care or Board and Lodge facilities almost always have multiple people per room. Therapies or meaningful activities are rarely provided. These places are very limited in the sorts of behaviors that they are equipped to deal with so once again evictions and dismissals via hospitalization are very common.

Once people are hospitalized- whether because of increased symptoms of their illnesses or because it was the only way to get out of their current living situation - there is an immediate emphasis on returning the person to the community as quickly as possible. Hospital beds are a very scarce and expensive resource. Yet chronic mentally ill people often do whatever is necessary to get into the hospital because it may be the only way that they know to get help finding alternative housing. It is extremely common for our clients to use hospitals when they are broke. Some seek hospitalization as a way to address medical problems that they couldn't otherwise negotiate. And some simply do best with the level of human contact, care, and supervision that hospitals provide. We can reliably anticipate that current budget cuts; new copays for medication, rehabilitation services, chemical dependency treatment; and the curtailment of health insurance for our indigent mentally ill and chemically dependent people will soon result in even increased pressures for hospital admission.

Our mentally ill citizens are frequently put into a position that they either must become very ill or emphasize suicidality in order to get into the hospital. It used to be that superficial wrist cutting was enough to guarantee hospital admission but things have become more competitive. Clients now know that the magic words are: "I'm hearing voices- they are telling me to kill myself...or someone else". Few emergency room Doctors will refuse admission to people that are saying that someone is going to die if they aren't admitted. More and more often we're seeing mentally ill people that need hospitalization in competition for hospital beds with people who don't even have severe mental illnesses. Chemically dependent people are having a real tough time in our society and many have learned that the mental health system is a good source of support. Many of them seek hospitalization as a way to get connected with entitlements and, especially, apartments. And they have already learned those magic words.

When the mentally ill in Minneapolis are deemed ill enough or dangerous enough to warrant hospital treatment they are sometimes hospitalized in distant communities, e.g. Duluth, Rochester, Mankato, or beyond because of a bed shortage in the metropolitan area. Severely ill patients are often denied hospital admission because beds are filled with people who have, by necessity, emphasized their dangerousness to self or others.

Many clients bounce from hospital to group home to apartment, living in several different places each year. Again, these are people who by virtue of problems with their nervous systems are the least capable of handling the stresses inherent in these kinds of changes.

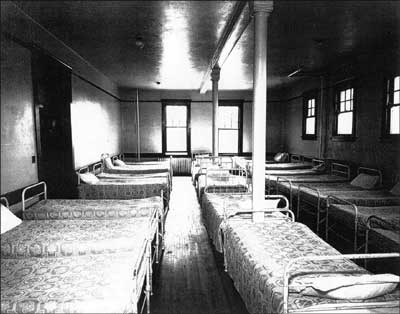

Homeless Shelter in Minneapolis

More mentally ill people sleep in shelters and prisons each night than sleep in hospitals. This is a picture of one of the better homeless shelters in Minneapolis. In fact you have to go through a nightly lottery to get to sleep on one of these mats. One untrained volunteer cares for about 70 adults, many of whom suffer severe mental illnesses.

The most noticeable difference between photos of State Hospital wards prior to deinstitutionalization and those of our modern shelters is that in the old days the sleeping mats had legs.

Mental Hospitals of old: Real beds with clean sheets.

At least in the old state hospitals when people were crammed together they had real beds to sleep on. More staff were available. Patients often worked at various types of jobs. And they didn't have to worry about where they'd be sleeping at night.

One of the strange things about our current system of community care for the mentally ill is that there is no way to predict who will end up in an apartment with several thousand dollars per month in services brought in, and who will end up in a shelter or on the streets. How ill you are isn't a determining factor. The real "safety net" in a society is defined by how far one has to fall before the net catches you. Sometimes our expensive safety net is left lying on the ground.

Secure waiting - mats will be available at 9:00

In Minneapolis "Secure Waiting" is where you end up if you have no place else to go and weren't "fortunate" enough to have won a lottery bed at one of the church shelters. About 250 people per night sleep on mats placed on the floor, only two or three inches from the next person's mat. A crowded, chaotic place to sleep and standing in lines at soup kitchens is the true safety net that our society provides its mentally ill people. And even this is costly. The tab for running Secure Waiting runs around 1.5 million dollars per year.

Not surprisingly, many mentally ill people opt out of this bizarre system altogether. Its often the very sickest people that end up sleeping in the streets. One of the most frequently cited reasons that our homeless mentally ill give for living on the streets or under bridges is that they just doesn't feel safe being around so many other people in the shelters, with all of their associated problems of poverty, theft, assaults, and substance abuse.

Still Occupied, Photo courtesy of Patrick Arden Wood

The bottom line is that our current system of providing housing for our chronic mentally ill is not working well for the clients themselves or for our society. This system is very cumbersome, inefficient, and extremely expensive but does not provide a meaningful and humane safety net that can be counted on to support our most incapacitated citizens. It is time to take a fresh look at this housing problem. A new understanding of mental illness and its long-term effects on people's functioning in the community is the most logical place to start.

What illness factors should be considered when designing housing programs for the mentally ill?

Perhaps the best way of approaching a problem of this complexity is a simple thought experiment. Imagine that there were no mentally ill people in our society. Then suppose that we suddenly had millions of them brought in from another planet and were faced with the task of assimilating them into our culture. If we really had the opportunity to start from scratch like this we'd certainly approach the problem of how to care for these people in a different way. We'd want to know as much as possible about our new citizens before we created programs to help them. And the programs that we'd develop would be specifically designed to meet the needs of these people.

The emerging models of mental illness are considerably different that those that were common when the deinstitutionalization movement began. There is a much greater awareness of the problems with neuronal migration and hook-up in the developing brain, and their ultimate role in causing mental illnesses. The longstanding, tenacious nature of many neuropsychological deficits has become more apparent. At the same time, the ability of the brain to change, at least to some extent, in response to environmental variables has also become better appreciated. What follows is a partial list of brain problems and adaptive capacities that should be taken into account as we try to develop the most humane and cost - effective programs to care for this segment of our population.

Altered Realities

Any housing or service programs that we develop must recognize that other people's realities can be very different from our own. We must also take note of the fact that mentally ill people will often have no awareness at all that their realities are different than other peoples'. The reality that our nervous system creates is the only one that we can experience.

About 70% of people with schizophrenia suffer from anosognosia according to a World Health organization study. Anosognosia is a neurologically based inability to recognize that one is ill. For a person with schizophrenia or other severe psychotic disorders to carry out the necessary comparisons between how they are now and how they were before becoming ill is akin to asking a color blind person to see green. We also ask them to make comparisons of how they think and feel while taking medications with their functioning in an unmedicated state. Most people without mental illnesses have difficulty making these sorts of comparisons. How many of us can accurately recall differences in moods that we experienced three months ago compared with today? But our current system of care is dependent upon the individual's ability to recognize that they are ill and seek help accordingly.

So our housing and service programs for mentally ill people must deal with some basic facts. People may be psychotic but will be unable to tell that their mind is playing tricks on them. They will be unlikely to embrace our medications or treatments- they are likely to experience our efforts to help as something that is inflicted upon them for problems that they don't really have. Many will be angry or demoralized because their lives haven't worked out in the ways that they expected and they won't know why. Most of these clients will have tremendous difficulties with empathy. They will be unaware of the minds, feelings, and realities of other people and are likely to behave in ways that we don't view as "normal".

If mentally ill people are going to stay in housing that we provide for them it will have to be because they believe that there is something in it for them to do so. It usually won't be because they believe that they have a mental illness and need treatment. They won't stay in any place because they are concerned about the financial costs to the system when they move from apartment to hospital to group home to shelter and back again.

We need to create living environments that people will want to stay in. Places where they are truly treated with dignity and respect. Places that are safe, secure, and provide good meals. Places where they have a sense of belonging to a community. Places that we'd feel comfortable living in too.

Managing contact with other humans

The ability to titrate one's degree of contact with other humans is one of the simplest factors that should be considered, but perhaps the most far-reaching in its implications. Many mentally ill people are estranged from family and friends and have no sense of belonging to any community. Bringing in staff for a few hours of house cleaning or socialization each week is helpful but does little to ease the feelings of anxiety and isolation that are so common in this population. Evenings and weekends are particularly difficult as few programs offer opportunities for social contact outside of normal working hours.

Neurologic deficits in empathy and self-awareness leave many of our clients lacking in social skills. Social advances may be clumsy or obviously based on fulfilling the needs of the moment, such as asking for cigarettes or money. Attempts to reach out to people in neighboring apartments are often met with rebuff. In other cases, the client is rapidly identified as vulnerable and apartments are quickly taken over by drug-dealers or homeless people. Going out after dark can be a risky proposition in many of the neighborhoods where our mentally ill can afford to live. Simply finding a place to be in the presence of other humans without being harassed or exploited can be a major undertaking.

As is often the case with the mentally ill, housing problems often fall into a "feast or famine"situation. Either they are lonely, with few prospects for meaningful socialization or they are stuck in the presence of other humans, with little chance of escape. In the majority of available housing environments if you aren't isolated in an apartment you're stuck in some sort of group home where you can't get away from other people. Small rooms with two or three roommates are very common. Opportunities for privacy are seldom available. It is no surprise that so many of the mentally ill in group homes prefer to sleep much of their days away.

This difficulty in finding an acceptable level of human contact that is within one's control has important neurologic effects. The importance of the hippocampus and associated structures in maintaining a decent mood and adequate cognitive functioning has been reviewed elsewhere. We have learned that lonely people tend to sleep poorly and impaired sleep affects the ability of the hippocampus to generate new brain cells. Memory suffers. Depression, irritability, impulsive behaviors, and substance abuse become more likely.

Humans are uniquely sensitive to the presence of other humans and this effect is undoubtedly magnified for our mentally ill. When another human is present we must immediately find ways to classify and deal with the relationship. Competitive and sexual feelings are quick to surface. Fear and anxiety are common. All of these emotional responses can trigger the release of stress hormones. These glucocorticoids can, in turn, directly impair the functioning of the hippocampus and limit its capacity to build essential new brain cells. So too much or too little contact with other humans can be difficult for humans to tolerate. Not having a sense of being able to control the degree of interactions with others makes these stressors more significant. And having a mental illness makes the issue tremendously more important. The brain structures involved are already abnormal so reserve capacity is much decreased.

A core component of any new housing programs for the mentally ill should involve providing an easy mechanism to control one's contact with other people. Small private rooms-even tiny ones- will usually be experienced as preferable to shared rooms. When designing group living spaces we should try to provide ways for people to be in the presence of others without being in each others faces, e.g. breaking up living spaces into smaller, more private clusters.

Deficits in foresight and planning

Another enormous area of difficulty for our clients results from the way their frontal lobes are hooked up and functioning. Many people with schizophrenia and other severe illnesses suffer a dramatic loss in problem solving abilities. Significant drops in IQ are very common with the onset of illness. These people essentially cannot use their "inner mental screens" to approach problems and imagine various possible outcomes. A sense of future is often lost. The ability to anticipate problems and actively plan for their solution may suffer as well. These abilities may be present to some extent, at some times, but quickly fall by the wayside when the person is under stress. Clients often act impulsively or try to access caregivers via problem behaviors in order to obtain help with problems that are experienced as beyond their capacity to deal with.

A good housing system will provide ongoing help with day-to-day decision making and crisis management. The real art comes in developing trusting relationships with the client, allowing them to deal with whatever problems they are capable of, and not imposing an unnecessary degree of control. These issues are often very difficult for new or untrained staff to conceptualize and deal with. Dependency, overcontrol, and oppositional behaviors can result when staff assume more responsibility for the client's life than is necessary.

Memory and cognition

Many mental health professionals are unaware of the memory problems that our clients must deal with. Impairment of both visual and verbal memory are common in the schizophrenias and other severe illnesses. Psychotropic medications often magnify these memory difficulties. Some clients do much better with one type of memory than another, for example recalling things that are written down more easily than things that are spoken aloud.. This sort of information is often available in existing neuropsychological testing but rarely seems to be utilized in the patients care.

A good system will identify memory difficulties and other cognitive problems when they exist. A variety of strategies can be used to help the client deal with these deficits, including established schedules and routines, prompts, and giving information in the sensory modality that works best for the individual. This is also an area where using technology will become increasingly important. In an ideal system all of our clients would have computer access and would receive routine information about medications, schedules, and activities via that route, in addition to others.

The importance of stimulation

We have learned that stimulating environments and novel experiences are very important for the very parts of the brain that so often are abnormal in the mentally ill. Unfortunately, our clients usually have tremendous difficulty in building these things into their daily lives. Our existing housing programs often ignore these needs completely. Many clients, whether they live in group homes or single apartments, have routines that are mind-numbing in their predictability. They never take vacations or travel to new places. They have little to excite or interest them. Nothing to look forward to or to set one day apart as special. For some, the only difference between weekdays and weekends may be less chance of contact with professionals on saturdays or sundays. An altered sense of time is very common among the severely mentally ill. Many do not even know what day of the week it is.

It's no wonder that so many of our clients turn to drugs. At least it sets some time apart as being different. Even feeling lousy might be preferable to always having things be the same. An informed system would try to maximize the amount of interesting and new experiences that its clients were exposed to. Trips to museums, cultural events, or just walks in new parts of town should be made easily accessible.

Psychoeducation is crucial

Many, if not most, of our clients do not carry an understandable explanatory model of their mental illnesses. They usually have been told that they have some sort of "chemical imbalance" but really have no idea what this means or what the implications are for their lives. Many have been told repeatedly that good medication compliance is essential for them but they don't see the benefits when they do take the medicines. Sometimes they feel worse when they take their meds, battling fatigue, sedation, weight gain, and confusion in addition to all of their other problems. They don't know who to blame for the loss of their dreams or what they can do to begin to recover a life that they can feel OK about.

A sound psychoeducation program for clients and staff alike should be a backbone of our system of care. When we suggest that someone participate in an activity, use a particular problem-solving strategy, or be more compliant with their medications we should be able to articulate in a clear and simple manner why it is in their best interests to do these things. Developing a culture in which their deficits are understood and recognized, while also appreciating their strengths and respecting their autonomy, will go a long way towards changing our system.

Transportation problems

Whenever groups of consumers are asked about problems in our system the issue of transportation is sure to come up. Minnesota is still an area where the vast majority of citizens get around by automobile and there are good reasons for this. Currently, transportation can be pretty good for those who qualify for medical transportation services but others have to travel 2 hours each way by bus to work for several hours at minimum wage jobs. It has recently becoming increasingly difficult to qualify for the medical transportation services. This is one of many areas where we actually provide incentives for people to achieve and maintain status as "disabled" rather than truly encouraging them to be more independent. We should make transportation a high priority whenever we design new housing programs or decide where to locate them. There is undoubtedly room for some innovation in this area. Finding productive employment is a huge task for many of our clients and many of them do drive. Developing van or car pools, operated by stable clients, to take people to appointments, make scheduled loops through the city, or hook them up with bus lines would be an upgrade to our present system.

The value of exercise

Physical exercise has emerged as perhaps the single most important factor impacting on one's mental health that a person can control. Yet very few of our clients exercise regularly. Creating a culture where exercise is a regular and valued part of the living environment will not be easy. Providing ready access to exercise via groups, YMCA memberships, tai-chi, yoga or essentially any activity that results in an improved connection between mind and body will be useful, especially if accompanied by the sorts of psychoeducation and explanations mentioned above. Meditation, treatment of depression with phototherapy lights, "sensory integration therapy" and other non-medication based treatments should also be maximized. There is no reason to limit our therapies to those that can be written on a prescription pad.

Negative Symptoms

Negative Symptoms of schizophrenia represent enormous barriers to successful community adjustment for our schizophrenic clients. Problems with will, motivation, sense of future, and forming decent relationships with other humans are extremely common among people with schizophrenia, as well as many others with different diagnoses. Compounding matters is the fact that negative symptoms generally do not respond robustly to medications. Oftentimes, medications actually exacerbate these problems via sedative side effects.

A Partial List of Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia

| Motor: |

|

| Social: |

|

| Emotional: |

|

| Cognitive: |

|

In most cases the genuine negative symptoms are a direct result of how the schizophrenic brain is wired. Many patients with pronounced negative symptoms have evidence of malformed brains very early in the course of their illness. When the brain creates its picture of reality it may not attach the right emotions or motivations that will activate the person to do something. While our present system is, understandably, very concerned with reducing "positive symptoms" like delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thinking it is actually the negative symptoms that have the greater impact on the patient's long term prognosis and functioning.

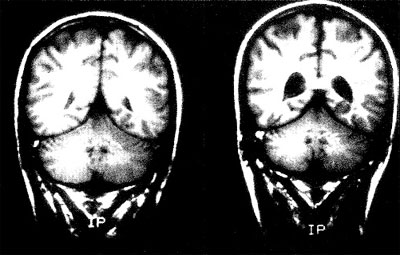

Schizophrenia in Identical Twins

MRI scans of 28-year-old male identical twins showing

the enlarged brain ventricles in the twin with schizophrenia (right)

compared to his well brother (left).credit/link

We need to provide training to staff and clients alike about the nature of these Negative Symptoms and strategies to deal with them. Without such an approach these problems will continue to be mistaken for laziness or character problems- with all of the dreadful consequences for individuals and families that are so common today. Developing environments that react positively to small successes but do not push the client to try to do more than they are ready for is another area that requires as much art as science.

Brain Plasticity and its Implications

In the chapter outlining an emerging model of mental illness we looked at the amazing flexibility that our brain's communication systems demonstrate. The experiment with monkeys showed how dopamine systems change in response to environmental variables. Having our own space is critically important. All sorts of stress reactions kick in when we are forced to share our living spaces with others. An acceptable place in our social hierarchy is also crucial for mental health. A perceived lower place on the social ladder may predispose us to anxiety, irritability, and substance abuse.

The glucocorticoid hormones that mediate our stress reactions have been proven toxic to the very brain structures necessary for a good mood . Memory can also suffer in response to stress. Yet we often house mentally ill people in environments that any sane person would be anxious in. Adding layers of major tranquilizers, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers may calm people down enough to survive in these settings but we shouldn't be surprised when problems with day- to- day functioning result.

In retrospect, moving severely mentally ill people from asylums to the community was doomed to be problematic right from the start - no matter how good the intentions were. We didn't appreciate the nature and extent of the disabilities that these people suffered from. We assumed that they would be able resume normal lives in the community once their most serious symptoms were controlled with medications. We did not have the knowledge or commitment to make sure that they would have a decent standard of living in the community- one that would allow them a fighting chance at recovery. Their poverty, lack of stable relationships, inadequate housing, and absence of a true sense of community have resulted in stresses that they were never equipped to deal with. We have tried to remedy this situation by adding expensive medications in increasingly greater dosages and combinations. But the findings from "Evidence Based Treatment" research consistently find that single medications in modest doses are effective for the majority of patients- at least when those patients are being housed in clean, decent hospital wards while the research is taking place. We cannot assess the way that brains function without taking into account the environments that they are functioning in.

The temptation is always to just keep doing what we have been doing. We can point to the wonderful successes that some mentally ill people have had with mainstream apartments when they were given the right sorts of supports. When things work well we should continue them. But we cannot neglect the fact that our current mental health system is a dismal failure for many people. Jails, homeless shelters, and the streets are filled with mentally ill people that have not benefitted from our system of care. No one can deny that these problems are increasing in our society.

We should face the fact that as a nation we do not have the will, the resources, or the commitment to provide each of our millions of severely ill people with a decent apartment and thousands of dollars per month in medications and services. Our current mental health system is overwhelmed by the sheer volume of people who need basic housing, food, and supports. No one is advocating for a return to the old asylums, or for taking away apartments from people who prefer to live that way. What our society needs is a spectrum of supported housing alternatives for mentally ill people. We have to develop programs that will serve large numbers of patients in the community in a humane, cost effective manner. And we need to do it quickly. Clearly it is time for us to look for new ways to provide a decent standard of living for our most incapacitated citizens. In the section on housing models we'll look at some common sense approaches to these social problems- solutions that would have been obvious back in the 1960's if we knew then what we know now. A paradigm shift is long overdue.