Readings in Humanistic Psychiatry

Model Communities for the Mentally Ill

This chapter will try to demonstrate how some new models of community care might look and function if we attempted to incorporate the core principles that were outlined in the previous section.

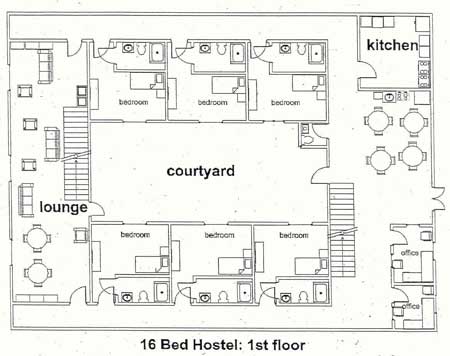

Model # 1: The Basic Mental Health Hostel

This model is a small footprint facility designed to house from ten to fifteen clients. It can fit onto lots in urban neighborhoods and may look like a family home from the outside. Each client is provided their own room with a door that locks. Individual bathrooms would be ideal but communal toilet facilities can be set up if budgetary demands dictate this.

A smaller hostel in Denmark

Construction should be economical and sturdy, but attractive and welcoming. A commercial kitchen is available for preparing group meals. A buffet style breakfast is provided for several hours in the morning and a full dinner each evening. Clients can also prepare their own meals if they wish. Nutritionists help to develop a variety of menu choices. Clients can learn to shop for the necessities and participate in preparing and serving the meals as part of their employment. Some facilities might become self- sufficient around meals, others might require some ongoing help.

Communal living areas would be built in, with particular attention paid to developing comfortable, flexible spaces that can provide some degree of privacy when it's desired. Security needs such as controlled access doors and video monitoring of common areas can be tailored to fit the needs of the facility.

Private meeting rooms would be provided for visits with mental health professionals. A multidisciplinary team similar to those found in Assertive Community Treatment models delivers the services, but without being bound to the rigid staffing requirements and "fidelity standards". The emphasis is on establishing good relationships with the clientele while not providing more help than people really need. The team of professionals would have to be nimble and responsive enough to meet changing clinical needs within the facility. Psychiatric care, nursing services, case managers, and security staff can be brought in to meet clinical situations as they develop.

An apartment for a live-in caretaker is provided. This could be a trainee in one of the mental health disciplines or a consumer who is stable enough to handle the work. Caretakers might have set hours in which they'd be available to the clients and would be able to readily access the team of professionals if the situation required it.

Consumers themselves would also be trained to access appropriate services when needed. Simple questions and communications might be handled through e-mail with case managers, nurses, or other service providers. Computer hardware, access, and training would be available on-site.

Much of the day to day operation and management of the facility would be done by the clients themselves. Cleaning, laundry, and maintenance functions might need some supervision initially but would likely become more independent over time. Clients would be paid a fair wage for any work, with the wages coming out of the pool of rent collected each month.

This model would lend itself to partnerships between public and private agencies. Philanthropic organizations could help pay for the building of the facilities or help to furnish them but wouldn't have to be involved in their ongoing operation or staffing. Contributions of food, supplies, and computer hardware can be actively pursued.

A lovely youth hostel in Rothskilde

These mental health hostels would be able to provide a decent standard of living for people at a fraction of the costs that we often pay for their care in the current system. Staff time would be used much more efficiently. Professional time would be titrated to actual clinical requirements rather than paying people to be available on site just in case they're needed. Ongoing, symmetrical relationships would develop between helping professionals and the clientele.

Because this is a residential model, and staff would be visitors to the residence just as in apartments, the needs around licensing and paperwork would be dramatically reduced.

This basic template could easily be adapted to meet the needs of special populations. Specialized Hostels for elderly clients, people with criminal histories, or chemically dependent people could be developed with relatively simple modifications.

While these Hostels are designed to meet the needs of mentally ill consumers they could also work well as a way to accommodate our increasing numbers of homeless poor. The needs for a private space, decent food, a sense of security, self-direction, and meaningful work are not limited to the mentally ill. They are human needs.

This rough floor plan is intended to demonstrate more than the difficulty that some psychiatrists have with spatial relationships. It shows one way that a small facility could begin to provide the combination of privacy and community that so many of these people need.

Basic features

Each client is provided with a single room with a door that locks. The units have small private bathrooms. Total size of each unit is about 225 square feet.

Rooms are provided for 15 people. The housing is intended to be long-term and voluntary. An apartment for a live-in caretaker is on the second floor and overlooks the entrance to the facility.

Ample opportunities for socialization and group activities are built in. This model includes two lounges, a common dining area, an exercise room, and a room that can be used for classes and therapy groups. The building is constructed around a private central courtyard.

Each client is provided with a small secure storage space to minimize overcrowding in the living units. Laundry facilities are available on-site.

Special features

While the physical plant itself is very important, a lot more must go into a model program like this if it's to be a truly innovative addition to our system of care for people with severe mental illnesses. This proposal incorporates some new approaches to a wide variety of problems that these people must deal with.

Service Delivery

In this model services such as case management, nursing, and psychiatric care are brought to the facility. The live-in caretaker serves as an interface between clients and service providers, as well as handling many small problems as they arise. The case management team titrates services to fit the actual needs of the clients. Flexibility and responsiveness are emphasized.

Nearly any level of care should be available, right up to hospital level services should they become necessary. Reducing the need for frequent moves based on changes in clinical condition will go a long way towards promoting mental health stability for these clients.

Two offices are provided for visiting professionals. Digital movie cameras are available for documentation purposes. The offices have Internet access and any record keeping is done on laptops. Lounges, the dining room, and the downstairs classroom are also available for informal meetings.

Education

This model emphasizes a frank, honest, psychoeducational approach to the illnesses that these clients suffer from. Deficits arising from the illnesses should be openly acknowledged and planning should take place around them. A classroom approach focusing on strategies for dealing with the illnesses may be more palatable for clients than the pure "therapy" models that are aimed at changing the person himself.

The classroom can also be used for a wide variety of other educational activities. Volunteers can be recruited to teach about special topics. Assistance with obtaining G.E.D.'s or learning English may be provided. The interests and curiosity of the clients themselves should determine much of the content of the classes that are offered. The educational component of the model may serve as a "magnet" and be opened up to other clients living in neighboring areas.

Vocational approaches

This model actively encourages and rewards employment for its clients. A basic principle is that whenever any work for the facility can be done by the clients themselves that should happen.

Janitorial services, shopping, meal preparation, laundry, yard work and other jobs are necessary in any facility like this and it only makes sense to use these areas to provide paid work for our clients. Even sitting with clients who are in need of extra attention or supervision can sometimes be done by residents. In the early stages they may need some extra training and supervision from professionals but that should decrease over time. Eventually, clients may be able to train other clients in how to perform these tasks.

Strong ties to community vocational programs should be built in as well. Vocational counselors can see clients right at the facility. An emphasis will be placed on finding jobs that are rewarding and make sense for the individual client. Teaching some clients how to work as cooks or food preparation assistants in group homes or restaurants can take place in the commercial kitchen.

We must take care not to build in any disincentives to employment. Even working a couple hours per week should be valued and will provide the client with some extra money. Wages for work done in the program should be fair and can be funded via the rent that is collected.

Dietary

The importance of good nutrition for optimal brain functioning is becoming increasingly apparent. There is room for a lot of variation here. This model incorporates a full commercial kitchen and provides meals in a group setting. A smaller adjoining kitchen is available twenty-four hours per day for clients that want to cook for themselves.

Dieticians will be involved in creating healthy menus that are attractive to the clients. Various levels of cooking instruction can be provided, depending on client interest and talent. Some people won't have any interest at all in learning how to cook. Others may want to learn how to shop and prepare meals for themselves in preparation for moves to apartments. And some clients may want to learn to work as professional cooks.

The commercial kitchen is built around teaching. A drop down panel can be opened up to provide a small classroom setting. Some clients may work shoulder to shoulder with the cook. This is another area where it may be necessary to involve a professional for cooking and supervision early on but clients might assume those duties over time.

Exercise

Few things are as important for healthy brain functioning as physical exercise. This model provides room for classes in aerobics and yoga. Donations of equipment like treadmills and weight machines can be solicited. Since so many clients have elements of Seasonal Affective Disorder and other circadian rhythm disturbances phototherapy lights will be built in to the exercise room. Physical exercise in the presence of the right sort of light can be very useful in relieving seasonal depressions, as well as resetting biological clocks.

Exercises that require coordination of both sides of the body may be helpful in boosting the activity of the cerebellum and may even have important effects on thinking patterns. Even going for walks can affect the way that we think and the emotions that we experience. Sensory Integration therapies may be helpful in helping the individual to learn to control the types and amounts of stimulation that their nervous system is exposed to. A good, multipurpose room that will support these various physical therapies is a sensible option to invest in.

Of course the brain needs exercise just as much as the body does. Research is making it clear that stimulating mental activities are necessary for good brain functioning. Games, puzzles, contests, and movies can all contribute to both quality of life and improved cognitive functioning.

It may just be a coincidence but it does seem strange that mental illness so commonly strikes people right about the time in their lives that they stop playing. Once the illnesses set in people typically abandon play altogether. And when mentally ill clients do have play in their lives nearly everyone seems to function better and have more satisfying lives. Play, fun, and enjoyment should clearly be more than afterthoughts as we try to develop optimal environments for these people to live in.

Economic Factors

Many of us await the day when a single-payer system of health care will be available in this country. That would be very helpful in guaranteeing decent access to housing, medications, and mental health services for these clients. Knowing that such basics will be provided without interruption would also relieve some significant stresses that patients may not be equipped to deal with.

The hormones associated with the stress response are now recognized as toxic to some very important brain systems-systems that are already malfunctioning for many people with mental illness. Keeping external stresses to a minimum is crucial if we are to truly give severely ill people their best chance of healthy emotional and cognitive functioning.

A simple model like this cannot change the way that health care is funded in this country. But we can create an arrangement in which the clients can experience the health care system as though universal health care were available. In a model program we can agree that complex problems involving reimbursement for services, entitlements, and so on will be handled without any impact on the client himself.

Professionals can deal with other professionals to resolve financial problems. Authorities in charge of funding can make some guarantee that rent will be paid and insurance benefits will continued regardless of the snafus that develop around lost forms, changing eligibility requirements, and other such bureaucratic entanglements. Allowing the client to be free of worries related to government programs that are not within his realm of control just makes good clinical sense.

The costs for building a 16 bed Hostel like the one demonstrated are estimated to run between 1.5 and 2 million dollars, depending upon whether land has to be purchased or tax-forfeited property can be used. That figure uses construction costs for quality buildings like college dormitories, roughly 150 dollars per square foot. Of course it may be possible to finance new construction for less in some areas of the country.

This certainly sounds like a lot of money and it is. But if one figures, very conservatively, that a well constructed residence like this would house mentally ill people for at least fifty years then a different perspective emerges. At that rate the yearly costs to house a person in one of these places would come out to be a bit under 1700 dollars per year. Probably a little better deal for both the client and society than those wall-to-wall shelter bunk beds that cost about 600 dollars per month.

The goal here is to create a model program that will be as close to financially self-sustainable as possible. If we can truly develop an approach that provides a better quality of life for these clients, at a reduced cost to society, the ripple effects may be enormous.

Psychiatric Care

In this model psychiatric care is offered right at the facility but, of course, clients should be free to continue treatment with outside psychiatrists if they choose to do so. Attaching a psychiatrist to the program should help in a number of ways: Bringing the doctor to the facility will be more efficient and cost effective than transporting 15 clients to as many different offices. The psychiatrist will have access to better sources of data by working with a team and seeing the clients in their home environment. Good long-term relationships with clients and meaningful therapeutic alliances will be easier to achieve.

Careful, reasoned approaches to medication should be utilized. Treatment should be informed by Evidence Based Practices and some common sense principles. Simple medication trials of adequate duration will be tried before moving to complex polypharmacy. We anticipate that lowered stress levels, better diets, and involvement in stimulating activities may reduce requirements for heavy doses of tranquilizing medications. Whenever effective generic medications are available we should use them in an attempt to keep total costs of care to a minimum.

Everyone is aware that medication non-compliance rates among psychiatric outpatients are abysmally low. Somewhere around a third to a half of clients really take their medications as prescribed. Mental health professionals frequently find themselves doing all sorts of things in an effort to improve medication compliance, including lecturing, threatening, hospitalizing, and even removing entitlements. But nothing really changes.

A model program provides new ways of approaching complex problems. A fresh place to start might be simply acknowledging that clients who do not have a court order to take medications do have the legal right to refuse them, as much as we might disagree with the decision.

Instead of forcing the client into a position where they abruptly abandon all medications, usually with negative consequences, we can seek a more reasoned middle ground. If they're intent upon stopping a medication we should be addressing the reasons for this openly with them. If we disagree we should be able to explain why, in terms that make sense to the client.

If they're still set on stopping the medication we should provide them with information about how to do this in the safest way possible. Usually this means gradually, with ongoing supervision and a way to determine if things are getting worse. We may offer the use of rating scales or even videotaped interviews to help them assess the effects of a change of this magnitude. And we should make it clear that if mentally competent clients discontinue medications that have proven effective for them, despite the best advice of professionals, they should bear responsibility for any behavioral problems or other consequences of their decision.

Many times clients refuse medications because this is one of the few areas of their lives that they feel that they have any control over. In a model program like this the need to use medications to battle for control should be dramatically decreased. Relationships with caregivers should be more equal and respectful. And admitting that the client has the right to refuse medications, even when we don't agree, further reduces the possibility that treatment for one's own illness will be used as a bargaining chip.

Record Keeping

Carefully documenting the results of all medication trials is essential for good psychiatric care. Yet clients themselves often can't recall what medicines they've taken let alone the effects that they had. And our medical record systems are increasingly based upon computerized checklist approaches that are aimed at maximizing billing rather that actually improving patient care.

We should make ongoing records of the effects of any medications that clients take. Target symptoms must be well defined and systematically tracked. Adverse effects have to be recognized and recorded too. Developing good records of the effects - both positive and negative - of various medications will help to shape the client's treatment throughout their lives.

Record keeping is an area where new technologies may prove extremely useful. Computerized rating systems around the effects of various treatments, using input from the psychiatrist, other professionals, and the clients themselves should be developed.

Recording interviews in which the effects of medications are discussed and documented would provide a way to track the results of medication trials and might dramatically improve treatment. We have the technology to store digital video records now. For clients, the chance to participate in this sort of ongoing assessment might change some underlying attitudes about medication, as well as providing them with direct evidence of how any particular medication affected them.

In this model the development of good medical records is clearly a joint venture between professionals and clients. We anticipate that clients will truly have a sense of ownership of their records, in marked contrast to how many experience our current record keeping. And this might help to foster a sense of ownership of their illness as well.

Other contributions from modern technology

Many routine communications with case managers, nurses, and other support personnel can be handled with simple e-mail. This proposal includes wiring the entire facility or using wireless technology so that everyone can have Internet access. This is another area where donations - in this case computer equipment - can be actively pursued.

The Internet is a vastly underutilized resource for mentally ill people. It opens up all sorts of possibilities for education and communication that most clients do not currently have access to. Interacting through computers can reduce some of the self-consciousness that mentally ill people often experience with face to face contact. Some clients may even acquire the skills to find employment in related fields.

Telemedicine is a rapidly growing field and having the facility wired for fiber optics may prove useful for arranging visits with professionals at remote sites. Building in video cameras to assist with security is another possibility should a facility need it.

Model Relationships

Forming symmetrical, respectful relationships with clients should be a cornerstone of any model program of this nature. In relationships of this type the client maintains control of, and responsibility for, his own life. Mental health professionals shift from being the "adults" in control of entitlements and client behavior to trusted consultants who try to help each individual recover the most satisfying life possible in spite of their illnesses. Professionals are seen as visitors in the homes of these clients, just as they would be in apartments or houses.

As much of the governance of the facility as possible is provided by the clients themselves. Staff can help to facilitate house meetings in which rules, expectations, and consequences for negative behaviors are decided upon. If a resident persists in behaviors that are troubling to his housemates they should have the capacity to vote him off the island. The first line of emotional support should ideally come from peer relationships too.

Laughter is turning out to have important effects on all sorts of brain functions, including crucial neurotransmitter systems. When staff are chosen to work in a model program one factor that should be heavily weighted is the interpersonal style that they have with clients.

Many of the best clinicians - regardless of discipline - manage to maintain a friendly, good natured approach with their clients. The illness is accepted and discussed matter-of-factly but it doesn't dominate or define the relationships. In good therapeutic relationships client and staff often find things to laugh about together. Involving staff members that are too strict, controlling, or punitive can undo many of the gains that a model like this should provide.

Legal Changes

Our approach to legal issues involving clients requires just as much overhaul as other aspects of the mental health system.

A model that emphasizes symmetrical relationships between clients and support staff will, hopefully, eliminate much of the need for contested hearings in the first place. When disputes about medications or consequences of illness related behaviors arise, attempts will be made to resolve them without court involvement. Input from peers and professionals that have established relationships with the clients will take care of many disputes. If court involvement does become necessary the mediation approach outlined earlier will be tried first.

When clients engage in behaviors that are illegal or disturbing to their neighbors we should use the principles of Restorative Justice to provide appropriate consequences. Many mentally ill people are not aware of the impact of their behaviors on others. Often this is a result of neurologically based failures of empathy. The Restorative Justice approach seems ideally suited to a mentally ill clientele. The offender learns how his behavior has affected others. Prescriptions for making restitution help to restore a sense of balance and ease underlying feelings of guilt.

If we're to truly help clients to become more responsible for their own lives we have to do a better job of fitting consequences to offences. And whenever we can help our clients to learn from these experiences we should do that.

Building In Good Outcome Data

A model program like this has a number of important functions. Chief among them is finding out what sorts of things work well - and which do not - for this patient population. We're still at a stage where systematically obtaining the right sorts of clinical evidence is much more important than deciding how to use the limited information that we already have.

We must build in good ways to determine outcomes. If a model does provide significant benefits for its clients and does so at a cost that is less than our current way of doing business we'll want to be able to reliably demonstrate that.

A variety of factors for the years leading up to entrance in the program can be measured, e.g. hospitalization rates, medication costs, days spent in employment, quality of life surveys, legal costs, and so on. Outcome data can then be collected and compared at various times during the client's stay in the facility.

We should strive to collect honest, meaningful outcome data and share it freely so that others may learn from it. As mentioned, financial costs should be measured in "real dollars", i.e. total costs to taxpayers and society rather than just looking from the budgetary perspective of a single agency.

We'll want to know how the clients experience the program, as well as how their families react to our efforts. If the model proves rewarding for the mental health professionals involved, we should be able to demonstrate that as well.

It's difficult to get at good outcome data once a program is up and running. Spending some time on outcomes beforehand, using the best instruments and techniques available, is in keeping with the spirit behind true Model Programs.

Model #2: The Specialized Apartment Building

This model is patterned after a level of care that is widely available in Denmark's mental health system. It offers many of the advantages of the Basic Mental Health Hostel, including private living spaces, community areas, and live-in staff. It's designed for people who are ready for more independence and self care. This model can also be used for couples and families.

A dedicated apartment building

The model involves using an apartment building specifically for our clients. A typical setting might provide apartments for six to eight clients but larger buildings can be utilized. One unit is dedicated to a live - in staff person or couple. As in Model #1, the caretaker oversees the workings of the facility and is responsible for interfacing with professionals should the clinical needs of the clients change.

A community area is provided for socialization and recreation. Meals are generally prepared by the residents in their apartments but communal meals may be offered on occasion. Help with shopping and transportation is part of the program.

Once again, this is intended to be a long-term housing model. All sorts of variations are possible, including using entire floors of existing buildings or apartments scattered throughout a complex.

All of the basic principles outlined earlier would apply in this model as well. Both privacy and a sense of community would be provided. The inefficiencies inherent in the scattered-site apartment model would be removed. Services are brought to the facility by teams that have ongoing relationships with the clients. Most of the ongoing work of the building would be taken care of by the residents.

The same ideas about treatment would apply here. Whenever possible the client stays in his own living quarters if psychiatric decompensations occur, rather than moving them to more structured and expensive facilities. Even paying someone to sit with a client around the clock, while this would very rarely be necessary, would still be more cost-effective than shipping the person off to a hospital.

One of the advantages of this model is that it can be produced without having to spend money on new construction. It would not, however, fit the needs of some of our more severely impaired clients. It requires more independent living skills than are needed in the basic Hostel model. It would probably not be as well suited to caring for the large numbers of severely mentally ill people that our systems must now provide for. But it definitely fits for some clients. And what our system needs is a rich variety of alternatives between the scattered site apartments and the overcrowded group homes.

This model bears some resemblance to the Fairweather Lodge programs that are scattered throughout the country. Locally these programs are called Tasks Unlimited. They have been extremely successful in providing work and long term housing for some mentally ill clients. People typically work in janitorial jobs, are paid a decent wage, and have a lot of say in how the homes that they live in are operated. Clients that do well in these programs sometimes stay for decades and have a good quality of life. Hospitalization rates typically drop off dramatically.

We should learn as much as we can from these programs. But the model described here would be applicable to a much larger pool of clients than the Fairweather models can serve. Most severely mentally ill clients are not considered for them because the work requirements are too stringent. We need to face the fact that many mentally ill clients, especially those with prominent "negative symptoms", are just not able to adapt to the demands of a forty hour work week.

In these models the work requirements would be much more relaxed. Clients would see clear and direct financial benefits from their labor. If they could only contribute a couple hours per week to their community even that would be welcomed. They would always have the financial incentives to do more if they were able.

Model #3: The Planned Community

This is a large facility designed to provide good housing for as many clients as possible, in the most cost effective manner that we can design. While many advocates for the mentally ill have traditionally been opposed to housing large numbers of clients together like this, it's hard to argue that this wouldn't be a dramatic upgrade for a great many clients. Some people regard the word "asylum" with distaste but it would be very interesting to see how many clients would want to stay in a place like this.

Many of our chronically mentally ill clients still long for the days when they could stay in large State Hospital campuses for years on end. Most of them will acknowledge that actual treatment ranked low on the list of things that they valued about these living environments. Security, a sense of community, a chance to form ongoing relationships, and freedom from the pressure to be constantly moving to new places are among the many factors that were important to these people. Many marriages and other lasting relationships developed in this climate.

Copenhagen hostel: 500 people per night?

This model is patterned after some of the large hostels that are found throughout Europe. The one pictured above, in suburban Copenhagen, houses about 500 people per night. Reservations are usually necessary to get a bed here. A room for a family of four runs around 60 dollars per night. A major difference between the European hostels and this housing model would be the continued emphasis on providing individual, private rooms for clients. That is not a common feature in the European hostels. But there are a number of other features that do carry over very well.

Housing a large number of people in one area provides obvious advantages in terms of efficient service delivery. Food can be purchased and prepared in bulk. Small kiosks offering most essential items are on the premises. Good public transportation is a given. Bringing professional services to places like this allows for many people to be seen on one trip.

Copenhagen Kiosk: Combination general store, front door watcher, and problem solver

Copenhagen Dining Room

These facilities are designed to offer meals on site. They provide better meals than many of us usually eat.

Copenhagen self-service kitchen

In these models people who want to cook for themselves have the opportunity to do so.

Sparkling clean bath rooms: Danes are tidy people

These large hostels often provide shared bathroom facilities. For people who are going to be living in these places long term it might be preferable to build small individual bathrooms into the units.

Model with enclosed courtyard

This type of design is a personal favorite. It's set up to house a lot of people but everyone gets a room with a window. The enclosed courtyard would be a wonderful touch for our clients, providing a sheltered place to be outdoors with others - and to smoke their ubiquitous cigarettes.

This planned community model shares a lot of features with some "Intentional Communities" that are sprinkled around the country and we should learn all we can from those models too. The idea of having a number of non-mentally ill people live in places like this, along with our clients, is quite attractive. Students could use these facilities for affordable housing. Almost anyone who ends up spending a lot of time with mentally ill people ends up seeing these people in a very different light. Exposing lots of people to mentally ill clients would go a long way towards reducing the stigma about mental illness that is still so prevalent in our society.

Once again, the basic principles that we develop to guide our programs and our interactions with these clients would all apply, even in large facilities like this.

Ideally, these planned communities would provide the desired spectrum of housing options right on the premises. Apartments or condos could be on the same property as the individual units. Creative opportunities for people to own their own space could be developed. There is no reason to limit the sorts of housing opportunities that can be imagined and built.

Of course the types of buildings that we create are important. But, ultimately, it will be what goes on inside them that will determine whether these are better ways to care for our mentally ill people. Changes in the nature and quality of our relationships with these clients will be the most important part of the paradigm shift that we need to bring about.

There is no downside

Even if it turned out that we were wrong about every single facet of these models (and that does seems rather unlikely since a psychiatrist is involved) an effort to develop the best and most cost-effective supportive housing programs possible will still be useful. We'll learn things that will make the next generation of model programs better. And we'll receive all sorts of other subtle benefits in the process.

The decision to go forward with a model program brings hope to providers in the mental health system, as well as the clients and their families. It can also bring people with diverse backgrounds together to ask what each element of a supported housing program could ideally look like. Creativity and optimism are in short supply in our mental health system these days.

Models will also allow us to try out new attitudes, assumptions, and approaches. Integrating services and housing in comprehensive and efficient ways will become possible. We could even agree to behave as though all human life has value - at least in one little model - just to see where a strange idea like that would ultimately take us. Any time belief systems are changed the effects can be far-reaching and unpredictable.

Creating a model program would require that we finally swallow hard and admit that we really do need to make changes. The mental health systems that now exist in our urban areas do not routinely provide a meaningful safety net for the mentally ill people that we already have. We're in no way prepared for serving much larger numbers of mentally ill people but they are going to be entering our systems whether we're prepared or not.

If we can really develop models that work better, and do so at a lower price tag, we can start replicating the programs, with whatever modifications are needed to serve other disability groups. Ultimately we have to start concerning ourselves with building capacity into our mental health systems.

Any of these models might end up looking different that the simple suggestions that have been outlined here. The important thing is not whether these proposals turn out to be the best of all possible models. It's whether we're honestly trying our best to create a better quality of life for the mentally ill people that society has charged us with serving.